Category: Philosophy

February 6, 2021

| I have been a HUGE Beatles fan ever since I first saw them on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Several years later I became a fan of the band Badfinger who reminded me of the Beatles. Well it turns out that the Beatles and Badfinger were connected…very connected. Badfinger was the first band that Apple Corps signed. The name “Badfinger” came from the working title for the song “With A Little Help From My Friends.” And two of the Beatles wrote songs for Badfinger. But despite this backing, Badfinger was struggling to be recognized and get on the charts. Paul McCartney came to the rescue by offering them the song “Come and Get It.” But the offer came with a condition: McCartney had to produce the song and it had to be done exactly like the demo tape he had recorded. From Songfacts: Paul McCartney recorded the demo of this song prior to a Beatles recording session at Abbey Road studios. He played all the instruments on the demo and had a clear vision for how it should sound. In The Beatles Anthology book, he explained that Badfinger wanted to do the song more in their own style, but he insisted they do it the same as on his demo, because he knew it would be a hit if done his way. He was right: the song was the breakout single for Badfinger. McCartney had a “clear vision” of how the song should sound and didn’t allow Badfinger to deviate a bit. And he was right, it was a big hit. But was it worth it? In this instance the band was merely a marionette. Yes, a successful marionette after following McCartney’s detailed direction, but a marionette nonetheless. What would you do if a prominent photographer said to you: let me manage your photography…I’ll tell where to go, what to shoot and how to process it. I’ll guarantee you success but you must follow my every direction exactly. Would it be worth it? You would enjoy success that would open doors and introduce your work to new audiences… But would it be worth it? If your goal is fame and accolades, then you might think so. But if you want to create images that you love and are proud of, then that success would feel fraudulent and unfulfilling. I believe we each must find our own Vision and not rely on the Vision of others. Copying other’s images, styles, techniques, following the latest fads or listening to others about your work is not the way to find your Vision. But rather forge ahead on your own, learn to know what you want, critically analyze your work, evaluate what you like and dislike about your images, learn from your mistakes and improve again and again and again. That is how you grow, develop your Vision and become independent. So, would it be worth it? For me the answer is no. I’d rather follow my Vision and be mediocre in the eyes of others rather than be a successful marionette. Cole

|

April 2, 2020

Tongariki, Easter Island

November 28, 2019

July 21, 2017

I’ve been listening to Brian Wilson’s book: I am Brian Wilson. A Memoir.

Something he said near the end really struck me: :

“You’d think that by the time I got to 60, I would have learned almost everything about singing. But that turned out not to be true at all.

I kept learning. And lots of that is about unlearning.”

I feel the same way. So much of what I’ve learned later in life about art, photography and especially about myself, has come about as a result of unlearning something.

As you have gotten older and wiser, have you found yourself unlearning anything?

Cole

P.S. If you don’t know who Brian Wilson is, you’re probably pretty young and haven’t started unlearning things yet, you’re still working on the learning part!

February 16, 2017

I’ve been posting an image a day on social media and have noticed that certain images are very popular and others are not. Often I find that my least favorite images are more popular than my favorite ones.

Let me give an example. There are two of images in my “less favorite” group that are very popular, they are Diminishing Cliffs (above) and Road to Nowhere (top). Don’t misunderstand, I do like these images, but I consider them two of my less creative and more mundane images. However they generate a lit of “likes.”

Here’s my dilemma: each time I post one of those images and get a flurry of “likes,” I am tempted to post more images like those. I am tempted to create more of the images that people want to see.

Why? Because I love the praise and the attention…I’ll admit it, I like the “likes!”

So what do I do? How do I respond to this conflict of interests?

I stop and ask myself: why do I create?

When I first started creating images, when I was a 14 year old boy, I created for the pure joy of creating. I created to please myself.

But over time other motives crept in. I found myself creating for positive feedback.

Then I started trying to win contests.

Then I argued that I needed to build a resume in order to be taken seriously as a photographer.

Then I was creating to be famous and to be respected as a photographer.

Then I was creating to make money from my photography.

And now, after some fifty years, I have come full circle and am once again creating for the pure joy of creating. What a long journey I have taken to learn the lesson that my 14 year old self knew!

The truth is that “likes” (or fame or fortune) are not bad, but I could never be happy producing work just to please others, no matter what the reward. The buzz from a “like” only lasts a moment, while loving my images produces an internal satisfaction that lasts a lifetime.

Life is much more simple when I try to please just one person…myself.

Cole

October 2, 2016

A good friend sent me these articles about writing and I thought to myself: the author really isn’t talking writing, but about creating. What he says applies to writing, painting, photographing and every other type of creative endeavour.

I like what Steven Pressfield says, a LOT.

Cole

Why I Write, Part One

By STEVEN PRESSFIELD | Published: SEPTEMBER 21, 2016

I stumbled onto the website of a novelist I had never heard of. (He’s probably never heard of me either.) What I saw there got me thinking.

What if we worked our whole life and never sold a single painting?

The site was excellent. It displayed all fourteen of the novelist’s books in “cover flow” format. They looked great. A couple had been published by HarperCollins, several others by Random House. The author was the real deal, a thoroughgoing pro with a body of work produced over decades.

Somehow I found myself thinking, What if this excellent writer had never been published?

Would we still think of him as a success?

(In other words, I started pondering the definition of “success” for a writer.)

Suppose, I said to myself … suppose this writer had written all these novels, had had their covers designed impeccably, had their interiors laid out to the highest professional standards.

Suppose he could never find a publisher.

Suppose he self-published all fourteen of his novels.

Suppose his books had found a readership of several hundred, maybe a thousand or two. But never more.

Suppose he had died with that as the final tally.

Would we say he had “failed?”

Would we declare his writing life a waste?

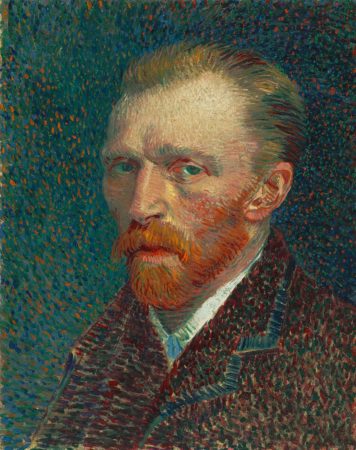

[I’m assuming, for the sake of this exercise, that our writer had been able somehow to support himself and his family throughout his life or that, if he had been supported by someone else (as van Gogh was looked after by his brother Theo), that that was okay with him and with the person supporting him.]

Then I asked myself, What if that was me?

How would I feel about those fourteen books? Would I consider them an exercise in folly? Vanity? Demented self-indulgence?

Would I say to myself, “What’s wrong with you? Why do you continue this exercise in futility? Wake up! Get a job!”

Could I justify all that effort and somehow convince myself that it was worthy, that it had been an honorable use of my time on Earth?

It won’t surprise you, if you’re at all familiar with my thinking in this area, to hear that I would immediately answer yes.

Yes, I would consider that hypothetical writer a success.

I might even declare him a spectacular success.

No, his writing life was not wasted.

No, he had not squandered his time on the planet.

And yes, I would say the same if that writer were me.

My own real-life career is not that far off from this hypothetical. I wrote for seventeen years before I got my first dollar (a check for $3500 for an option on a screenplay that never came near getting made.) I wrote for twenty-eight years before my first novel was published.

What, then, constitutes success for a writer? Is it money? Sales? Recognition? Is it “expressing herself?” Is it “getting her ideas out there?”

Or is it something else?

I’m going to take the next few weeks’ posts and do a little self-examination on this subject, which I think is especially critical in this era of the web and Amazon and print-on-demand and instant and easy self-publishing, these days when literally a million new books appear each year. How do we, how do you and I navigate these waters, not just financially or professionally but psychologically, emotionally, spiritually?

[Thanks to our friend David Y.B. Kaufmann for suggesting this topic.]

Why I Write, Part Two

By STEVEN PRESSFIELD | Published: SEPTEMBER 28, 2016

If you’re a writer struggling to get published (or published again) or wrestling with the utility or non-utility of self-publishing, you may log onto this blog and think, Oh, Pressfield’s got it made; he’s had real-world success; he’s a brand.

J.K. Rowling has earned her spot on the Elite List

Trust me, it ain’t necessarily so.

I don’t expect to be reviewed by the New York Times. Ever. The last time was 1998 for Gates of Fire. That’s eighteen years ago. The War of Art was never reviewed, The Lion’s Gate never. My other seven novels? Never.

I’ve got a new one, The Knowledge, coming in a month or two. It will be reviewed, I’m certain, by no one.

If I want to retain my sanity, I have to banish such expectations from my thinking. I cannot permit my professional or artistic self-conception to be dependent on external validation, at least not of the “mainstream recognition” variety. It’s not gonna happen. I’m never gonna get it.

If you’re not reviewed by the New York Times (or seen on Oprah) your book is gonna have tough, tough sledding to gain awareness in the marketplace. No book I publish under Black Irish is going to achieve wide awareness. BI’s reach is too tiny. Our penetration of the market is too miniscule. And even being published by one of the Big Five, as The Lion’s Gate was by Penguin in 2014, is only marginally more effective.

There are maybe a hundred writers of fiction whose new books will be reviewed with any broad reach in the mainstream press. Jonathan Franzen, Stephen King, J.K. Rowling, etc. I’m not on that list. My stuff will never receive that kind of attention.

Does that bother me? I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t want to be recognized or at least have my existence and my work acknowledged.

But reality is reality. As Garth on Wayne’s World once said of his own butt, “Accept it before it destroys you.”

On the other hand, it’s curiously empowering to grasp this and to accept it.

It forces you to ask, Why am I writing?

What is important to me?

What am I in this for?

Here is novelist Neal Stephenson from his short essay, Why I Am a Bad Correspondent:

Another factor in this choice [to focus entirely on writing to the exclusion of other “opportunities” and distractions] is that writing fiction every day seems to be an essential component in my sustaining good mental health. If I get blocked from writing fiction, I rapidly become depressed, and extremely unpleasant to be around. As long as I keep writing it, though, I am fit to be around other people. So all of the incentives point in the direction of devoting all available hours to fiction writing.

I asked hypothetically in last week’s post, What if a writer worked her entire life, produced a worthy and original body of work, yet had never been published by a mainstream press and had never achieved conventional recognition? Would her literary efforts have been in vain? Would she be considered a “failure?”

Part of my own answer arises from Neal Stephenson’s observation above.

I wrote for twenty-eight years before I got a novel published. I can’t tell you how many times friends and family members, lovers, spouses implored me for my own sake to wake up and face reality.

I couldn’t.

Because my reality was not the New York Times or the bestseller list or even simply getting an agent and having a meeting with somebody. My reality was, If I stop writing I will have to kill myself.

I’m compelled.

I have no choice.

I don’t know why I was born like this, I don’t know what it means; I can’t tell you if it’s crazy or deluded or even evil.

I have to keep trying.

That pile of unpublished manuscripts in my closet may seem to you (and to me too) to be a monument to folly and self-delusion. But I’m gonna keep adding to it, whether HarperCollins gives a shit, or The New Yorker, or even my cat who’s perched beside me right now on my desktop.

I am a writer.

I was born to do this.

I have no choice.

March 25, 2016

From the New Camera News (http://newcameranews.com/2015/04/01/shocking-nikon-canon-to-end-camera-development/)

In a rare joint statement, industry giants Canon and Nikon have announced that both companies will cease all camera development, effective immediately. At a hastily arranged press conference both Nikon and Canon stressed that they are not getting out of the camera business per se, but rather will continue with their existing product lines for the foreseeable future “and quite possibly forever.”

When asked why the two companies were making such a radical decision, Canon said, “Hey listen, our current camera lineup is good enough. As a matter of fact, internal research has shown that our cameras are better and more capable than 99% of the people that own them. With data like this, the only logical thing to do is to stop improving our cameras until our owners become better photographers.”

“That’s so true!” Nikon interjected. “For years we have peddled this notion that the only thing keeping you from becoming a ‘professional’ photographer was access to the latest and greatest gear. ‘Buy this new camera!’, ‘Buy this new lens!’ we’d say in our advertising, ‘and you’ll take better photos immediately!’ Great food photos. Great puppy photos. Great photos of a perky young Japanese lady near a cherry blossom or by a water fountain or something quintessentially Japanese. But deep down inside we knew that you were just going to be the same crappy photographer you’ve always been but with more megapickles.” After reflecting for a moment, Nikon added, “It feels so good to say this. To finally get this off our prism.”

“You feel good?” Nikon asked Canon.

“Wow. Better than I’ve felt in decades.” Canon replied.

“You wanna go get a beer?”

“Sure.”

March 6, 2016

My philosophy is: Don’t. Ever. Never.

Why? Because my opinion, no matter how well intentioned or experienced, is bound to miss the mark.

Why? Because my advice comes from my point of view, my Vision and my definition of success.

Not yours.

If I really want to help someone, I’ll offer encouragement instead of advice. If I do comment I’ll say only positive things and qualify my comments with a “what I like about this image is…”

I’ll never tell another person what they should have done or what I would have done with the image. This is not useful, no matter how well intentioned I am.

If the person presses me for an opinion, then I’ll simply say: What I think is unimportant. What do you think of the image? How well does it express your vision?

Generally I find that a person asking for an opinion does so because they have not yet found their Vision. This now opens the door to talking to them about the importance of Vision as the driving force behind an image and not relying on the opinions of others.

And above all else I try to be kind and encouraging. I try to remember that each person is on the same path as I am. Today they may be behind me on that path, but tomorrow they could be ahead of me.

That’s a great reason to treat each person as I would like to be treated: as one who has tremendous creative potential and is seeking to find their Vision.

Cole

February 26, 2016

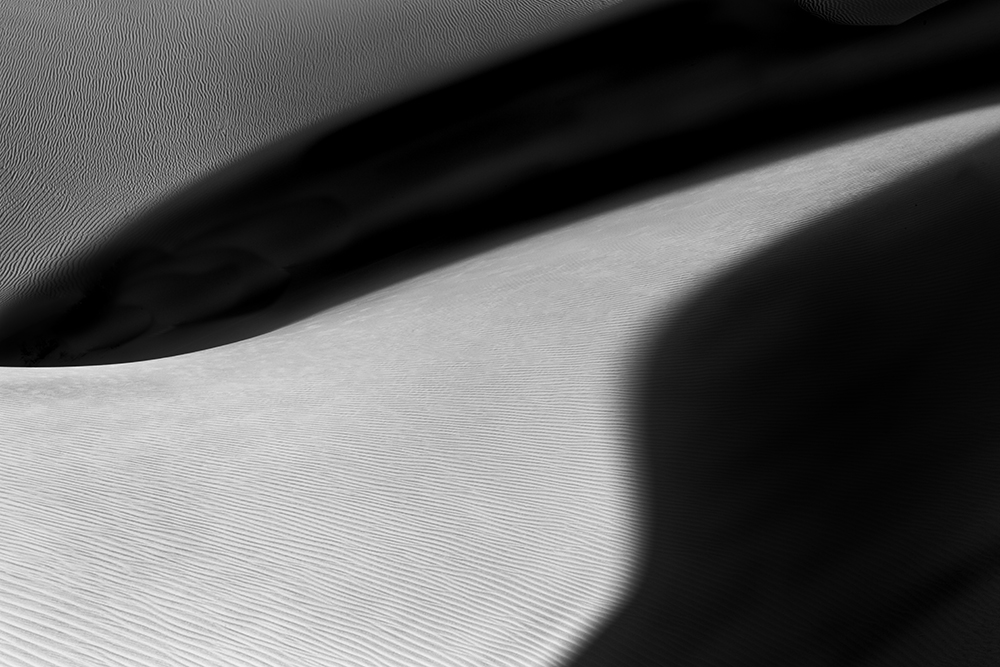

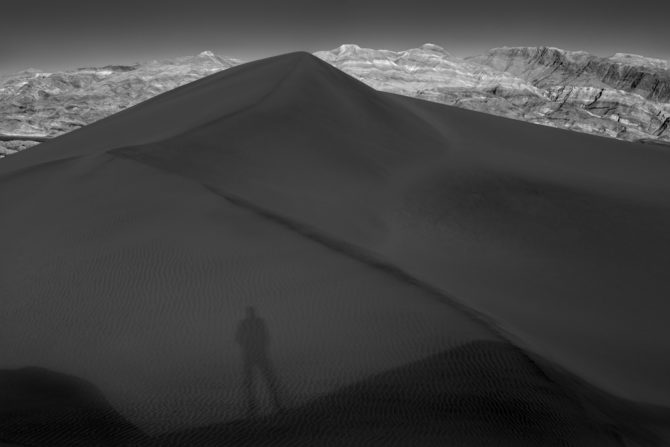

Dunes of Nude No. 119 (from my recent Death Valley trip)

Last week I asked the following question:

Someone is looking at your work and says: tell me about your Vision.

How do you respond?

Here’s my response:

When you look at my images, you are seeing my Vision.

Why use inadequate words to describe my Vision when the image says everything?

~ ~ ~

Only once in my life have I tried to put my Vision into words: a friend, blind from birth, asked me to describe my work and Vision to her. I asked how could I describe things which she had never seen? She said that she created mental images based on my descriptions. I’ve always wondered what my images looked like to her.

~ ~ ~

I enjoyed everyone’s comments and could see that semantics, different perspectives and honest differences of opinion were all in evidence. May I offer my viewpoint?

Vision can be elusive and hard to discover, yet I believe it to be an incredibly simple concept:

Vision is simply how I see things, based on my life experiences.

Because we’ve all had different life experiences, we all have different Visions. But everyone has a Vision!

Vision is much different than a look or a style. And once you start following your Vision, your work will not all start looking the same. Vision transcends a look, a style and techniques.

Vision is expressed through our images and unlike Harvey the Pooka, your Vision can be seen by everyone (you have to be over 50 or a movie buff to get the reference).

Vision is the most important ingredient in your image, it’s what makes it unique and “yours.” It is more important than your camera, lens, process or any piece of software that you use. And no amount of technical perfection, unusual technique or unique subject matter can compensate for a lack of Vision.

An image without a Vision is just a…well, just a picture.

Cole

February 20, 2016

Someone is looking at your work and says: tell me about your Vision.

How do you respond?