I talk a great deal about Vision, because it changed my photography. It helped me make the transition from “taking pictures” to “creating images.” And the lessons I learned about following my Vision, helped me to change my life. You see, following your Vision is not really about photography, it is about life. Here’s where my Vision story begins: |

|

Several years ago I was attending Review Santa Fe where I was hoping to be discovered. Over the course of a day my work was evaluated by a number of gallery owners, curators, publishers and “experts” in the field. During the last review of a very long day, the reviewer quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back to me and said: “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I replied that I was, because I loved his work! He then said something that would change my life forever: “Ansel’s already did Ansel and you’re not going to do him any better. What can you create that shows your unique vision?” Those words really stung, but the message did sink in: Was it my life’s ambition to be known as the world’s best Ansel Adams imitator? Had I no higher ambition than that? I desperately wanted to know if I had a Vision, but there was a huge problem: what exactly was Vision? |

|

Is Vision a look, a technique, a style? Is it something that you learn, is it something that some people have and others do not? It turns out that it’s none of those things. Vision is simply the sum-total of your life experiences, that allows you to see the world in a unique way. |

|

Imagine if you could take everything that you’ve experienced in life, everything you’ve been taught, and everything you’ve learned…and melt that down so you could cast lenses, that you saw the world through. And what you see through those life-lenses, is your Vision. It’s simply how YOU see. |

|

When I stand before a scene, I can see what that final image will look like. How I imagine that final image is based in part on my tastes (b&w), my likes (centered images), and preferences (high contrast)…which are all a part of my Vision. |

|

But there are other voices in my head that sometimes distract me. How would Ansel see this scene? |

|

Or perhaps I’m hearing the voice of my camera club judge who told me that my images were too dark, and that I needed to open up my shadows. |

|

Or I’m following the advice of my mentor who keeps telling me not to center my subject. |

|

And what about the rules? Maybe I should change how I’m seeing to conform to them? |

|

Here’s the problem: Vision cannot coexist with those other voices! You must either choose to follow the rules, the judges, mentors, experts and social media “likes”…or follow your Vision. The two choices are diametrically opposed to one another. But to follow your Vision, you must first find it, and from my experience, that’s not very easy. Unlike our cameras that come with a manual, or PhotoShop with its thousands of YouTube instructional videos, Vision has no manual or guides. And because I had no idea on how to proceed, I simply came up with ten ideas that I thought would help me find my Vision. |

|

1. Sort Your Portfolio I took 100 of my best images, printed them out and then divided them into two groups: the ones I REALLY loved…and all the rest. I decided that the ones that went in the “loved” pile had to be images that “I” loved, and not just ones that I was attached to because they had received a lot praise, won awards or sold the best. And if I loved an image that no one else did, I still picked it. Then I analyzed each of those images in the small stack and asked myself: What do I love about this image? I did not ask myself: what do these images have in common, because that didn’t matter to me. And it was then I had a small peek into my Vision; I love dark images, contrasty images, centered and symmetrical images, I love simple images, unusual images, and I love photographing wildly varied subjects. At the time I didn’t understand how important these little discoveries were, but now looking back, this was a very important first step. 2. Make the Commitment I committed that from that point on, I would only pursue those kinds of images, the ones that I really loved. Too often I had been sidetracked when I chose to pursue images simply because others liked them. It was through this step, that I began to recognize the corrupting influence of praise. Criticism could sting for a bit, but praise could turn my head. 3. Practice Photographic Celibacy I started practicing Photographic Celibacy and stopped looking at other photographer’s work. I reasoned that to find my Vision, I had to stop immersing myself in the Vision and images of others. I used to spend hours and hours looking at other photographer’s work and would then find myself copying their style or even their specific images. I knew that I couldn’t wipe the blackboard of my mind clean of those images, but I could certainly stop focusing on their Vision and instead focus on mine. When I looked at a scene I didn’t want to see it through another photographer’s eyes, I wanted to see it through mine! Initially I thought I’d only practice Photographic Celibacy for a short time, while finding my Vision. But here I am now, some 15 years later, and still find the practice useful. 4. Simplify Your Processes I embarked on a mission to simplify my photography. In the past I had focused on the technical and now I was going to focus on the creative. I disposed of everything that was not necessary: extra equipment, gadgets, plug-ins, programs, processes and all of those toys we technophiles love. I went back to the basics which simplified my photography, and gave me more time for focus on the creative. I was very surprised at how effective this step was. Yes, simplification did give me more time to focus on the creative, but more importantly it changed where my focus was. 5. Ignore Other’s Advice I ignored the advice that well intentioned friends and experts gave me. So much of this advice had never felt right for me and I was torn between following their recommendations or my own intuition. In the end I decided that only by pleasing myself could I create my best work, and that no matter how expert someone was, they were not an expert about my Vision or what I wanted. Here’s some of the expert advice that I had been given: - Follow the rules of composition

- Lighten your images

- Open up your shadows

- Don’t center the subject

- Focus on one genre and become known for that

This advice never felt right to me, but I followed it because it came from the “experts.” 6. Change Your Mindset I worked to change my mindset from photographer to artist. I had always thought of myself as a photographer who documented, but I could see that this role was limiting and the truth was that I wanted to be an artist that created. To help me make this mental shift, I started calling myself an artist (I felt like such a fraud at first) figuring that I must play the part to become the part. I also stopped using certain words and phrases, for example instead of saying “take a picture” I would say “create an image.” That may seem like small and inconsequential things, but it helped to continually remind me that I wanted to be an artist who created, and not a photographer who documented. 7. Question Your Motives I questioned my motives and honestly answered some hard question such as: Why am I creating? Who am I trying to please? What do I want from my photography? How do I define success? It seemed to me that Vision was something honest and that if I were going to find my Vision, I had to be honest about the reasons I was pursuing it. 8. Stop Comparing I stopped comparing my work to other photographers. I noticed that when I compared, it led to doubts about my abilities and it left me deflated. All I could see were their strengths and my weaknesses, which was an unfair comparison. I decided that if my goal was to produce the best work that I could, then it did not matter what others were doing. I had to remind myself that this was not a race or a contest, I was not competing against others…I was trying to be my best self. 9. Stop Caring What Others Think I made a conscious decision to stop caring what others thought of my work. I recognized that in trying to please others, I was left feeling insecure and empty. At the end of the day, it was just me, my work and what I thought of it. As long as I cared what others thought, I was a slave and could never be free. 10. Get Inspired I re-read Ayn Rand’s novel “The Fountainhead” which I had first read at age 17. It has been one of the most influential books of my life because it gave me hope that I could become truly independent, that I could think for myself and define my own future. I know this book can cause strong reactions in people, both for good and ill, but it was a tremendous help in finding my Vision. I also re-read Edward Weston’s Day Books, and re-read them annually. I just really connected with how Weston thought, and this also inspired me to become independent and to follow my own Vision. |

|

I’d love to report that in a very short time, I found my Vision, became wildly successful, and lived happily ever after…but that just ain’t so! For two years I worked really hard on finding my Vision, and nothing happened. I still didn’t understand what Vision was, and I still had no idea if I had one. At times I became so discouraged with my seeming lack of progress, that I considered giving up my search. I thought that without Vision, I could at least continue on as a technically proficient photographer. I believe the reason I couldn’t understand Vision, was because I was searching for a complicated answer. |

|

When really, Vision is so very, very, very, very simple. |

|

Vision is simply how I see, when I push all the other voices out of my head. So how and when I did I “discover” my Vision? I had been working hard for two years, to push out all of those other voices, to create for the right reasons, to ignore what other’s were doing and to not care what other’s thought of my work. And then one day, in a simple and quiet moment of understanding, it occurred to me that I was now creating from my Vision! I had “let go” of all of that other stuff, and I was creating what I loved and how I loved it. And once I had found my Vision, it all seemed so obvious and simple. |

|

I hear this often: I’ve tried, but I just can’t find my Vision. One of the most important truths I learned about Vision, is that we all have one. You cannot, not have one, because it is simply your point of view, or how you see. So please do not think that you’re the one person who doesn’t have one. You do. But let me ask three hard questions: |

|

How badly do you want it? I wanted to know if I had a Vision more than anything else. It consumed me and I thought about it almost every day for those two years. And I was willing to work hard for it, and sacrifice for it. A story: I was giving a live presentation in New Jersey, and I explained how I practiced Photographic Celibacy as a way to help me find my Vision, when man in the audience stood up and said (incredulously): “You do what? Why on earth would you deprive yourself of the pleasure of looking at beautiful photographs?” I responded: “Because I wanted to find my Vision, even more than I wanted to look at beautiful photographs.“ How badly do you want it? |

|

What have you tried? Simply wishing that you had a Vision is not enough, you must work hard to find it. I didn’t have any idea of how to proceed, but you have the advantage of my ten steps. And while I cannot guarantee that these will work for you, I do sincerely believe that they will help. |

|

If you were to divide up the time you spend on your photography, how much is spent on the technical verses dedicated to finding your Vision? I spent two years, working daily to analyze my motives, to learn what I loved, and to train myself not to care what others thought of my work. It was hard, soul searching work, with lots of self-analysis (all done while I was working a full time job and raising a family). How much time are you willing to spend to find your Vision? Finding your Vision is a solitary journey, and it takes time… |

|

This is The Angel Gabriel, and this was the first image that that I consciously created from my Vision. As I stood there, I could see the final image in my head. And from that point on, that’s how I created my images. |

|

It’s what I call Cole’s Rule of Thirds: A great image consists of three parts: 1/3 Vision 1/3 The Shot 1/3 Processing But it’s the Vision that comes first, and what drives the shot and the post-processing. Without Vision, I would take the shot and then just play with it in Photoshop, hoping to stumble upon a great image. And once in a while, I got lucky and would find one. |

|

Finding my Vision allowed me to evolve from “taking pictures” to “creating images.” For me, creating an image goes far beyond what your eyes see. I love what Edward Weston said about this: “Why limit yourself to what your eyes see when you have such an opportunity to extend your Vision?” What my eyes see, is just the beginning of the process. My eyes can inspire me, but it’s my Vision that allows me to “see.” Here is my favorite quote on Vision, ironically from a blind woman: |

|

If you are serious about improving your photography, consider focusing on your Vision, with at least as much time and energy as you spend on developing your technical skills. Vision will improve your work to a much greater degree than any technical improvements that you can make to your photography. |

|

Midjourney by Jason Allen (and AI)

It was recently revealed that an award winning photograph was actually AI generated. I was discussing this with my son Caleb, who is majoring in Computer Science, and the question arose: is an AI generated photograph, a real photograph?

A day later, Caleb emailed me and said that he had posed that question to ChatGPT, which is an AI chatbot (think of the computer HAL in 2001).

Here is AI’s response to the question:

The answer to whether a photograph created by AI is a “real” photograph can be somewhat subjective and depends on how we define “real.” From a technical standpoint, a photograph created by AI is a digital image file that can be viewed and shared just like any other digital photo. However, there are some important differences between photos created by humans and those created by AI.

One key difference is that photographs created by humans are typically the result of a deliberate and intentional act of capturing an image of a real-world subject through a camera lens, whereas AI-generated images are created through an algorithmic process that may not involve an actual subject or a physical camera. This means that AI-generated images may not necessarily represent something that exists in the physical world.

Another difference is that photographs created by humans are often valued for their ability to capture a moment in time and convey a sense of reality or authenticity, whereas AI-generated images may be valued more for their esthetic or creative qualities. In this sense, the concept of a “real” photo may be less relevant for AI-generated images.

Ultimately, whether a photograph created by AI is considered a “real” photo depends on the context in which it is used and the purpose it serves. In some cases, an AI-generated image may be just as valid and valuable as a photo taken by a human photographer, while in other cases, the distinction between a “real” photo and an AI-generated image may be more meaningful.

Wow, not a bad answer, but it’s a little creepy being referred to as a “human” by a computer.

This week I had friend write an article for his Club’s newsletter, in which he talks about how he described an image to DALL-E (an AI system that can create images) and he then shows the result:

Find Your Vision

Thanks to the amazing job Serge does as the Programs Director for WPS we have one spectacular speaker after another at our meetings. And one of the positive side effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has been our Zoom meetings where we have been able to invite speakers from geographically distant places.

Last night’s program knocked it out of the park again: Cole Thompson came to us from his home in Colorado and gave an awesome inspirational talk illustrated with many of his projects.

He talked about finding your vision and not listening to what other people think your vision should be, or what “rules” you should follow, and that certainly one should not copy someone else’s vision.

He shared an anecdote from his early days when his photography imitated Ansel Adams. A critic told him “Ansel already did Ansel. What can you do that exhibits your unique vision?” That led to a sudden epiphany, and as he put it, he didn’t want to be known as “the world’s greatest Ansel Adams imitator”.

Lately generative AI has been in the news everywhere. ChatGPT has been all over the mainstream press, most recently on the cover of the current (February 27th) issue of Time Magazine. Before that, everyone was talking about OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

While I certainly don’t want to be the world’s greatest Cole Thompson imitator, inspired by him, I thought I’d have a little fun with DALL-E and see what I could do. So with the prompt,

“A moody high contrast black and white portrait of a cat in the style of Cole Thompson with long exposure motion blur clouds and ocean in the background”

Meow, Sitting for Portrait

Scary, huh?

So, what’s your vision? I hope you share some of your images in our Member Showcase meetings, or even here in our newsletter. Till next time, may you always see beauty in your viewfinder.

–Fuat Baran, President (Westchester Photographic Society)

AI clearly doesn’t do cats very well (unless it was portraying the cat in long exposure?) Nonetheless, this is a fairly impressive and yet scary image, that gives a hint of what’s to come.

AI is a hot topic, and I doubt it’s going away. I suspect my views on it will evolve with time, but for right now, I would not feel good about creating an AI generated image and then calling it a photograph or calling it “mine.”

Stranded If you wanted to improve your photography and you could do just one thing…what would it be? What, among all of the many possibilities, would help you create better images? I Googled this question and here are some of the many ideas I found: - Buy a better camera

- Take a Photoshop or Lightroom class

- Study the work of Photographers that you admire to get some new ideas

- Join a photo club

- Take a photo workshop

- Go to a great location that inspires you

- Study and better understand the rules of composition

- Learn more about your camera’s capability

- Get closer

- Learn to shoot in manual mode

- Use a tripod

- Slow down

- Learn more about light and the best light to photograph in

- Purchase prime lenses

- Develop a unique style

- Photograph things that no one else has photographed

- Deconstruct famous photographs to see why they work

- Experiment with different techniques

- Create images that are like the most popular ones on social media

- Have your work critiqued

- Learn new skills by recreating the photos that you admire

Some of these suggestions may be appropriate if your goal is to take better family and vacation photos. By all means learn more about your camera, Photoshop, and some compositional rules to help keep telephone poles from sticking out of head of your subjects! But if your goal is to create images, not just take pictures, as a form of self-expression, then my suggestion would be to throw out all of the items on this list. Some are simply time wasters, some send you down the wrong path and others are actually harmful to the creative process. Yes…you do need to know the basics on how to operate your camera and your post-processing software, but you certainly don’t need to be an expert to get started. Most of what I know about my camera and software, came about as I needed to do something specific. For example: I have never needed to use layers and so I’ve never spent the time to learn them. But now I have a project that can only be done with layers and so I will learn it with the help of my friend John Barclay (whom I’ve been trying to help become a better photographer for years, but I fear it is hopeless!) The items above are all red herrings and should be ignored, in my opinion. Okay, it’s easy to tell people what NOT to do, but what would you recommend someone do to improve their photography? If you could do just one thing to improve your photography, it would be to find and follow your Vision. That is the driving creative force behind all my images. It’s not the camera, the software, the location, the rules of composition, following photographic fads, or imitating others. For me, it’s finding my Vision and following it. Knowing what I love and pursuing it. Ignoring what others are doing and creating images that I love, regardless of what anyone else thinks of them. Nothing can compensate for a lack of Vision! Shooting with a prime lens at the optimal aperture means nothing if you have a boring, lifeless image. And having the world’s most complicated post-processing routine will not help a poor and uninteresting composition. I know because that’s the path I followed for so many years! I took that technical path because I didn’t think I had a Vision or any creative ability. I also followed that path because learning your camera and photoshop is not only fun, it’s straightforward and concrete. And finding your Vision is the exact opposite of straightforward and concrete. First, Vision is such a difficult concept to understand (until you’ve found it, and then it’s so ridiculously simple). Second, there are no instruction manuals on how to go about finding your Vision. And Third, it takes a lot of difficult and sometimes painful introspection to find your Vision. It took me 35 years to get to a point of even wanting to find out if I had a Vision, and then two long and hard years to do so. |

|

Ceremonial Wash Basin Now, if I could expand beyond this one suggestion, and offer one more: Critically analyze your own work. I personally find this recent trend to have one’s work critiqued by an expert disturbing. What you are getting is only an opinion and there are many of those out there. And the critiquer’s opinions are colored by their Vision and their personal preferences. And so whose opinion should you listen to? I say listen to your own, it’s the most important one if you’re trying to create work that you love. Experts may be expert in many things, but there’s one subject they can never be an expert in: your Vision. So how do you improve without hearing suggestions and new ideas? By critically analyzing your own work…that’s what I do. Study your image and ask what you could do to make it better, and more in keeping with your Vision. What do you like and dislike about your image? Is there something you could change to make it better? If you could do it over, what would you do differently? Another technique I use to analyze my image is to process it, let it sit for a week and then analyze it again. Sometimes it goes straight in the trash bin at that second viewing. Then I’ll tweak it, let it sit for another week and do it again…and again…and again if necessary. At the point that I no longer make changes to the image, it is finished. When you have found your Vision, your opinion is the only one that matters and you have no interest in the opinion of others. Once you have found your Vision, there are no need for critiques. |

|

If you could do just one thing to improve your photography…I hope you’ll consider finding your Vision, because Vision is the single most important tool in your toolbox. Here is an article which details the steps I took on my Vision journey. |

|

Hi everyone, as you might remember I was to present at Out of Death Valley in January, but our dear friend Covid had other ideas.

So now I’m scheduled to participate in Out of Chicago Live! 2021, which being a webinar event, is certain to take place.

I’ll be participating in three ways:

First, I’ll be presenting my “Why Black and White” presentation. Now, if you’re thinking “yeah, yeah, I’ve heard that presentation before.” Think again Ansel, it changes almost every time I present it!

Second, I’ll be conducting a class called “The Photoshop Heretic” on my super-simple Black and White processing approach.

And thirdly, I’ll be participating in a panel discussion entitled “Are You A Photographer or Artist?” A topic I’ll enjoy since I’ve been on both sides of that fence.

There are a lot of great people participating and lot of friends!

- John (I taught him everything) Barclay

- David (he loves my donkey) Kingham

- Jennifer (I love her dolphins!) Renwick

- Brooks (how does he do it all?) Jensen

- Chuck (whom I’ve never met) Kimmerle

- Sarah (my Colorado neighbor) Marino

Should you attend Out of Chicago Live! 2021? Hop on over to their website and check out the program and you decide!

https://www.outofchicago.com/conference/live-2021/

But I will be there, stirring it up and being 100% honest…but always with respect for another’s point of view.

Cole

I’ve been doing a lot of Zoom presentations to Camera Clubs and recently I’ve been getting feedback that I’ve never heard before…and it really surprised me:

Thank you for giving me permission to create what I love

Thank you for giving me permission to ignore the rules

Thank you for giving me permission to listen to myself

My first reaction was horror! Who am I to give anyone permission? I worried that I had presumed too much and crossed a line in my presentation.

My second reaction was bewilderment. Why do people think they need permission to do what they want?

My third reaction was sadness. It seems that the message so many people come away with after taking a photo class or joining a camera clubs is: here are the rules that you must follow to create good images.

And then they hear my message:

Don’t follow the rules

Create what you love

Don’t listen to other’s advice

And their reaction is often relief and excitement. Relief that they don’t have to follow the rules and excitement that they can follow their own instincts and create for the pure joy of creating.

But of course following this path comes with a price: others may not like your work, they may even be critical of it and you probably will not please judges or reviewers who believe in following rules.

But what would you rather do? Follow their advice and create images that they love but you don’t…or follow your own heart and create images that you love.

If it helps, you have my permission to ignore the rules, follow your Vision and create images that you love.

When you read these “Ten Things That I Would Never Do” you may disagree with one of them, you may disagree with several of them and you might even be offended…

Please don‘t be!

These are not ten things that YOU should never do, but ten things that I will never do…again.

1. Offer advice about someone else’s image.

Why? Because that advice would come from my perspective and Vision, not theirs.

People often ask me: what would you do with this image? And I say: if I were to tell you what I would do, and you followed my advice and you kept following my advice, soon your images would look like mine.

And please believe me, you don‘t want that. Ansel has already done Ansel and Cole has already done Cole. You want to do “you.”

Monolith No. 50

Created with a Manfrotto 3021 Pro Tripod and Lowepro Bag Model 200 AW.

2. Give technical specifications.

I hope you smiled when you read the technical specifications above image and said to yourself: the tripod and bag don’t have anything to do with this image!

I don‘t believe any specifications, including camera, lens, aperture, shutter speed and etc. have anything to do with an image either. It distracts from the image and worse, listing specifications furthers the false belief that they are the key to the image, when the real key is the creativity and Vision of the artist.

A few years back I submitted an image to a publication which responded that I “must” include the technical specifications…but they didn’t say which ones.

And so I gave them the specifications of my tripod, including how far the legs were spaced apart for the shot.

They did not respond…but published the image.

3. Use watermarks.

I think it sacrilegious to put a watermark on an image, it’s so distracting that it ruins my viewing experience.

I know the arguments for using them, but I love my images far too much to desecrate them in this way.

4. Copy someone else’s idea.

“Lesser artists borrow; great artists steal.”

Pablo Picasso.

I have no idea what Pablo was thinking, but I have to disagree…big-time.

Everyone sets their own standards, but in my quest to create “honest work,“ I refuse to borrow or steal.

But sometimes I do create work that is similar to others…

Several years ago, I submitted my “Grain Silos” portfolio to LensWork. Brooks Jensen responded that he liked the work, but that he had just published something very similar in the current issue by a photographer named Larry Blackwood.

The irony was that Larry and I were friends, and unbeknownst to each other we were working on similar projects and had produced similar results. This resulted in Brooks writing an article about Fellow Travelers who sometimes create similar work.

Coincidences…cool.

Borrowing someone else’s idea…not cool.

5. Imitate someone’s work and send it to them.

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.“

Charles Caleb Cotton

Here’s another generally accepted maxim that I disagree with.

I would never photograph “Half Dome“ like Ansel did, email it to him and proudly say: “Look what I did!“

When someone imitates one of my Harbinger images and sends it to me, I’m not flattered (however I‘m never offended either because I know their intentions are kind).

So what is the sincerest form of flattery? For someone to say: “I love this image!“ or loving it so much that they hang it in their home.

6. Ask someone what I should do with one of my images.

If I were to ask someone what should I do with this image, it would reveal something very important about me: that I don’t have a Vision for this image.

Instead of asking for someone else’s Vision, I should find my own.

Vision is what makes my image “mine.“

It’s what puts my mark on it.

It‘s what gives it spirit.

It’s what makes it more than “just a photograph.“

7. Shoot in color.

My eye has always been drawn to Black and White and I’ve never had an interest in color. Outside of family photos, I have only created two color images, one of them is above.

Ironically, I shoot all of my images in color and then convert them to black-and-white. When I’m converting them and can see the color and b&w image side-by-side, the color image rarely appeals to me.

But for some reason this one caught my eye, perhaps because it is so monochromatic?

8. Seek out the iconic shots and photograph them.

When I go to a location, I never research the iconic shots or seek out the “must see” sites.

Why?

Because millions of others have photographed those locations a billion times before and I don’t want to create another “me too“ image.

9. Offer limited editions.

I cannot imagine printing The Angel Gabriel image 25 times and then not being able to print it again because it was in an edition of 25.

I could never do that…I would never do that.

In my opinion there’s only one reason to offer a limited edition: to artificially create scarcity to inflate the price. Fortunately for me, I do not pursue photography for money.

When I was trying to decide if I should offer limited editions, I asked the editor of LensWork, Brooks Jensen, what he thought. He asked me this question:

“Would you like to say that your work sold for thousands of dollars, or that your work was in thousands of homes?”

I knew what I wanted! I now number my prints, but in an open edition. If I’m lucky I’ll print a million copies of The Angel Gabriel!

I’ve had people refuse to purchase an image when the discovered it was not in a limited edition. That told me they were more interested in an investment, than the image.

I want people to purchase my image because they love it, not because it’s a “good investment.”

10. Attend a portfolio review.

When you get a portfolio review, you are getting the opinion of that person.

Opinion!

Embedded in that opinion is their Vision, their likes and dislikes, their prejudices, phobias and everything else. And the thing is, there are hundreds, no thousands, no millions of opinions out there!

Which one should you listen to?

Your own.

I don’t believe in portfolio reviews because I value my opinion of my work more than a reviewers.

A story:

A young artist was exhibiting his work for the first time and a well-known critic was in attendance.

The critic says to the young man: “would you like to hear my opinion of your work?”

“Yes” says the young man.

“It’s worthless” the critic says.

“I know” the artist replies, “but let’s hear it anyway.”

Experts may be expert in many things, but there’s one thing they can never be expert in: your Vision.

I’ve received one portfolio review in my life and the only good thing that came of it was a commitment to find my own Vision.

And finding my Vision changed my photography…and my life.

Criticism can be devastating,

but praise can be even more dangerous

In May of 2008 I created The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau which was widely published and exhibited. In addition to the public success, I consider the work a personal success because I love and am proud of the images.

And with the success came congratulations, praise and then the advice….

The overwhelming consensus was that I needed to strike while the iron was hot and take advantage of the publicity the project was receiving. I was encouraged to create additional ” The Ghosts of… ” projects and ride the wave of success.

It was suggested:

- The Ghosts of 911

- The Ghosts of Little Big Horn

- The Ghosts of Manzanar

- The Ghosts of The Killing Fields

My initial reaction? No way! I was inspired to create the Auschwitz series and unless I was inspired to do another location, I’m not interested.

But the praise and encouragement just kept coming in: fantastic!…brilliant!…do another Ghost series… ride the wave…take advantage…you have a winning formula…this could be your ticket to the big time!

Slowly I was seduced and finally I agreed. I chose as my next Ghost project: The Ghosts of Great Britain . It was to be shot at the castles of England.

So off I went with my family in tow. My young daughter was to be my ghost and she brought her ghost costume: a white sheet with eye holes cut out. We went from castle to castle with her wearing the sheet as she spun or walked slowly for 30 second exposures.

It was a fun trip and we had some laughs as other tourists looked on, wondering what we were doing.

Old Wardour Castle

When I got home and processed the images…I absolutely hated the results and scrapped the project. I kept only one image, “Old Wardour Castle” above.

Why did I hate the project? Because it was not inspired, it was not borne from Vision and I had no Passion for the project. Instead it was a contrived marketing strategy.

In Cole-Speak: it wasn’t an honest project.

It was an expensive failure, but it provided two invaluable lessons:

First, trust your instincts. Other’s advice may be sincere and right for them, but it may not be right for you. In this instance my definition of success was quite different than how the advice-givers defined success.

Second, I was reminded of the powerful influence praise has. I was too easily seduced and set aside my standards.

Not cool.

This experience reinforced my belief that criticism can be devastating, but praise can be even more dangerous.

Georgia O’Keeffe addressed this:

“I decided to accept as true my own thinking.

I had already settled it for myself, so flattery and

criticism go down the same drain, and I am quite free.”

My goal is to be be free from the opinions of others, for good or for ill. But the truth is that praise is a seductive siren that beckons, influences and sometimes changes my actions and opinions.

Even today as I show these images, I worry that if I were to start receiving positive comments about them I would be persuaded to change my opinion of them.

If others love them…maybe they’re not so bad?

Maybe I was wrong, maybe these are good images?

Maybe that “Ghosts of…” idea wasn’t so bad?

And while I’d like to think I wouldn’t let that happen, this is exactly what did happen a few years ago with another one of my images: I traded my values for popularity.

But that’s a story for a future newsletter.

Tongariki, Easter Island

Perhaps you’ve noticed that for the past several years, most of my best images were created in exotic and far away places such as Easter Island, Ukraine, Newfoundland, Hawaii, Alaska, Poland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

You see the same coming from other photographers: exotic images coming from exotic lands. The conclusion is obvious:

To create great images you must go to great locations!

But that’s a lie.

The real truth is this: great images are created anywhere you can see them. Even at home, your back yard or hometown.

To illustrate this proposition I gathered together some of the images that I had created within 15 minutes of my home:

An abstract created on the Poudre River, minutes from my home.

Seen along I25 in Ft Collins, CO

Almost home when I saw this storm cloud

I’m driving with my daughter and son in the back seat, when I noticed her enjoying the warm summer day with the window open and her eyes closed.

In my backyard.

From my “Ceiling Lamp” series, this lamp is at the Mourning Dove Ranch, which is my home.

Looking for Grain Silos when I found these chairs.

Found while working on the Grain Silos series.

This is an old set of silos located right in town.

The Poudre River, near my home.

Two small cherry trees in my backyard.

A autumn day at at tree farm.

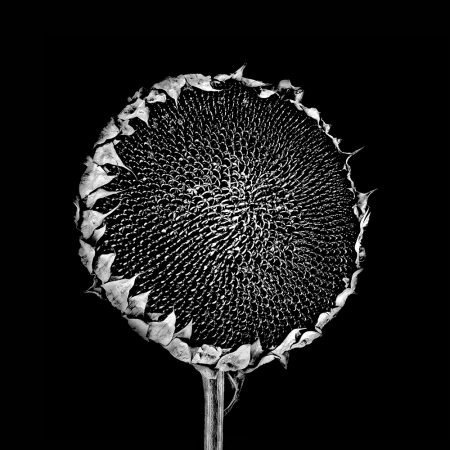

I found this sunflower on the ground alongside a field of sunflowers.

This is Ingrid. These are cows.

Ingrid wanted a “unique” photo for her yearbook.

I photographed this storm system just a mile from home.

I was driving in a snowstorm when I saw this Cottonwood. I love cottonwoods and fortunately I always have my camera with me.

I found this in an old and somewhat dangerous trailer park along the river.

It was raining and so I grabbed some leaves and nuts from outside, and photographed this on the kitchen table with a bare bulb.

A local cow.

Wandering about when I saw these tracks.

With one dahlia, I created a small series of images.

This is the dahlia, I found it discarded and on the ground at a local nursery.

At this greenhouse, was a tool room, but I couldn’t find any lights. So a penlight and a long exposure were used to create this image.

A pressed dandelion from years earlier, photographed in my office.

This old 34 Chrysler was found down the road in my neighbor’s yard.

This old bicycle was also found in my friend Frank’s yard.

A “Frozen Pond” near my home.

My cat Wiggles was sitting on my office chair, in this image she is yawning, but I didn’t think that the title “Wiggles Yawning” sounded very good. Instead this was named “Wiggles Roaring.”

This “Skeleton” was found as is along the Poudre River.

I was pumping gas at the Forks when I saw this “Packard” behind the gas station.

A long exposure water abstract created at a spillway on the Poudre River.

I found this detail in old abandoned home.

A melted shower enclosure in an old burned out home.

A few years back almost all of my work was created locally, but then I started to travel. Photographing in exotic locations was exciting and easy, but it made me a lazy photographer.

When you go to a place like Easter Island, you cannot NOT come away with a great image, they almost fall into your lap! The same is true in the Faroe Islands, everywhere you point the camera is a great shot.

Travel photography is easy because I’ve chosen a location that I find particularly interesting. It’s easy because I can leave all my cares at home and focus 24/7 on just one thing: creating. It’s also easier because I come to each new location with “fresh eyes.”

Shooting at home is much more challenging. At home I’ve got a million things on my mind and a million things to do, that’s two million distractions! And this makes it hard to photograph because almost anything, no matter how small, seems to take priority.

I also find it difficult to get into a creative groove when I’m creating in bits and spurts. One minute I’m a house-husband, the next a photographer, then a grandpa and then a photographer, then a rancher and again a photographer…I find it hard to switch in and out of creative mode.

But the virus is here, most of us are restricted in our travels and photographing at home is the new reality. And instead of seeing this as a negative restriction, I see it as the silver lining of an otherwise dark cloud.

I believe the real test of creating isn’t cherry-picking great images from great locations, but rather to see the extraordinary in the ordinary. To be able to find something remarkable in my everyday surroundings.

Edward Weston, who is my photo-spiritual guide, was confined to a chair in later life with with Parkinson’s when he said:

So I look at the coronavirus home confinement not as a curse, but a blessing. Travel photography is fun and it’s helped me create some great images, but it’s made me lazy. I’m now being challenged to really see again.

So here’s how I plan to approach this challenge:

First, I’ll set aside time to go out and shoot every day. For me, the more I shoot, the more I see. My biggest challenge will be to not let the little things distract me from getting out.

Second, I must learn to see past the mundane. When you’ve lived at one location for years, it becomes ordinary to the eye. And so here’s a little game I play when I’m in a location where I cannot see: I pretend that I’ve created a time machine and have brought back all of the great masters of photography: Adams, Weston, Strand, Caponigro, Bourke-White, Lang, Bullock and others. I ask myself if they were turned loose on this location, could they find a great image?

And of course I know the answer before I ask it: Yes.

And once I’ve decided that a great shot must be there, I look for it.

Third, when I’m juggling a lot of balls at home, I go into hyper mode, which is great for getting things done but exactly the opposite of what’s needed to be creative.

So what I have to do is slow down…I need to slow my heart rate and my thinking. I need to empty my mind and just see and feel.

I do this by stopping, sitting and looking. This helps take some of the “hyper” out of me and allows me to connect with my surroundings.

I don’t know how long this virus is going to restrict travel, but I’m hoping to use the time to develop some new creative habits and to train my eye to once again see wherever I’m at.

Dark clouds always have silver linings, if you look for them.

The Fox – Anaheim 1971

I was talking with some friends recently and they asked why I write these articles. I thought about my motivations and wanted to share them.

First, I don’t do it for the money…because there is none! I don’t sell advertising or subscriptions.

I don’t do it to win followers. I tend to alienate as many as I endear – just bring up Photographic Celibacy at your next gathering of photographers and see what happens.

Maybe I do it for the likes? No, I’m not very likeable.

Or perhaps I want to be an “internet influencer?” (I don’t really know what that means)

Here’s the truth of it: I write because I know there are many photographers out there who are in the exact same place that I found myself some 15 years ago::

- I didn’t believe I was creative

- I had no idea if I had a Vision

- I wanted more than winning ribbons and earning likes

I write about my experiences and what I’ve learned to help others who are find themselves in a similar place.

Self-Portrait – 1969

My Photographic Story

My story begins at the age of 14 when I was living in Rochester, NY. A friend and I were out hiking when we came across an old house that my friend said had once been owned by George Eastman. That piqued my interest and so I downloaded Eastman’s biography from iTunes…I mean I checked out Eastman’s biography from the school library (coincidently I’m re-reading that biography right now).

I was immediately fascinated by photography and before I had finished that book, before I had ever taken a picture or seen a print develop in the darkroom, I was convinced that I was destined to be a photographer. This sounds silly I know, coming from a 14 year old boy, but that is how I felt then and how I still feel today.

And so for the next several years, photography was my entire life. My every waking moment was spent reading, photographing and experimenting. I skipped so many classes because I was out photographing, that I barely graduated high-school.

I grew up with no art or music in the home, and because I was not taught to be creative, I came to believe that I wasn’t. I surmised that you were either born with the creative gene or you were not…and I definitely did not have it (this is something I frequently hear from other photographers).

This belief reinforced my conclusion that photography was the perfect art form for me. While it was creative, it was also technical. I decided that I could compensate for my lack of creative ability by excelling in the technical.

Looking back at that now, it seems like a silly thing to believe, but that’s what I thought…or perhaps what I hoped.

Men Watching Construction – 1970

I had been self-taught but now I was planning to attend College for a formal photographic education. But unexpectedly I had this jarring epiphany: if I chose photography as a career, it might become “just a job” and I could lose my passion for it. I didn’t want that and so I chose a career in business and planned on pursuing photography as a passion in my spare time.

What I didn’t know is that while raising a family and building a career, there would be little spare time left for photography. And so for the next 30 years, my personal photography largely languished.

Fast forward to 2004: my children are older, I have a little more free time and digital photography is making its way onto the scene. I decide that I’m now ready to return to photography and learn digital.

And so I picked up right where I left off: pursuing photography as a technical art and turning out average images that looked just like everyone else’s. They were technically good and followed the rules of composition but they were mundane and soulless. They could have filled a calendar of cliché images quite nicely, but they didn’t fill my soul.

I also began entering contests and started to win, which was exciting…at first. But I noticed that winning didn’t change my life and it didn’t make me any happier…and in fact the opposite seemed to be true.

Winning was leaving me with this empty feeling and I wasn’t sure why.

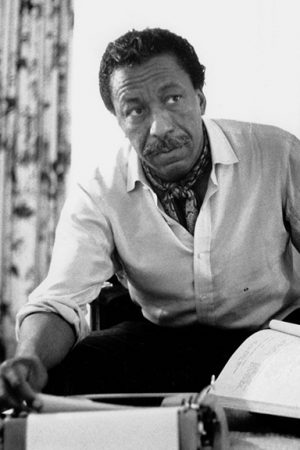

Vered Galor

About this time I made friends with an artist, Vered Galor, who became my mentor. She and I could not have been more different: she was an artist who created using photography and I was a technically oriented photographer who documented. These differences were the basis for many a “spirited discussion” about photography and art. Vered would encourage me to be creative and I’d resist, telling her that I thought it was a photographic sin to “manipulate” an image.

Looking back, the truth was that I didn’t know how to create and I didn’t believe that I had it in me. I told myself that I wasn’t creative for so long, that it had become a fact.

Fortunately, Vered was stronger willed than I was and she kept pushing me to move beyond documenting. Slowly I started down the path by first desiring to be creative and then by believing it was possible.

One thing that I did to help me remember my goal of becoming an artist, was to change the words that I used. For example, instead of saying that I was a photographer I would tell people that I was an artist who used photography. You cannot imagine how phony I felt doing this! I could barely call myself an artist without feeling guilty and blushing.

But it reminded me of what I wanted to become.

The Angel Gabriel

My focus on being creative was starting to work and I soon began “creating images” more often than “taking pictures.” The Angel Gabriel was the first image that I consciously “created” and it remains to this day one of my best images.

Thanks to Vered’s influence, I had started to transform from photographer to artist. I wish you could have known me back then so that you could appreciate the magnitude of the transformation that has taken place.

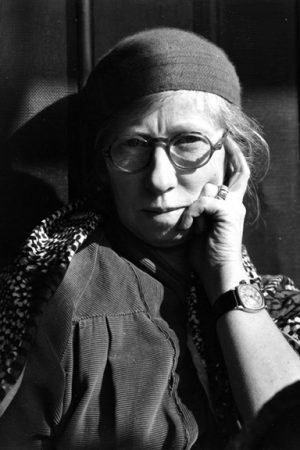

Vivian Maier

Edward Weston

Gordon Parks

Imogen Cunningham

What about this idea that some people are just more creative than others? Look at artists such as Weston, Cunningham, Parks and Maier…they seem more creative than the average photographer.

Perhaps these artists are more creative because they have focused on their creative side more. I spent 50 years focusing on the technical and my creativity atrophied. Can I really expect to be their creative equal after only a few years practice?

If you want to be creative, focus on the creative.

Review Santa Fe

Finding My Vision

Several years ago I was attending Review Santa Fe where over the course of a day my work was evaluated by a number of gallery owners, curators, publishers and “experts” in the field.

During the last review of a very long day, the reviewer quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back to me and said “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I replied that I was, because I loved his work! He then said something that would change my life:

“Ansel’s already done Ansel and you’re not going to do him any better. What can you create that shows your unique vision?”

Those words really stung, but over the next two years the message did sink in: Was it my life’s ambition to be known as the world’s best Ansel Adams imitator? Had I no higher aspirations than that?

I desperately wanted to know if I had a Vision, but there was a huge problem: what exactly was Vision and how did I develop it?

I researched Vision but I couldn’t relate to the definitions and explanations that I found. Was it a look, a style or a technique? Was it something you were born with or something you developed?

And then there was the nagging doubt: what if I didn’t have a Vision? I feared that it was something you either “had” or you “didn’t have” and perhaps I did not?

And how was I to go about finding my Vision?

With so many unanswered questions and with no idea on how to proceed, I simply forged ahead with what made sense to me. I came up with 10 ideas that would help me determine if I had a Vision.

I really was proceeding blindly, but I believed that if I listened to my own desires, pursued what I loved and eliminated all other voices, I would learn something about my Vision.

I did this for two years and there were many times that I became discouraged and didn’t feel like I was making any progress. I didn’t really know what I expected to happen, perhaps I thought I’d have a revelatory experience where my Vision would suddenly appear in a moment of inspiration!

But that didn’t happen.

And then one day it just occurred to me: I understood…I understood what my Vision was.

It came in an anti-climatic and quiet moment of understanding, and after all of that worrying and angst…it now seemed so incredibly simple. Vision was not something I needed to acquire or develop, it had been there all along and all that I needed to do was to “discover” it.

Vision is simply how you see the world!

Vision was simply the sum total of my life experiences that caused me to see the world in a unique way. When I looked at a scene and imagined it a certain way…that was my vision.

My Vision had always been there, but over the years it had been obscured by what I call “Vision Blockers.” Some of my Vision Blockers were:

- Valuing other people’s opinions over my own

- Imitating other photographer’s work, look or style

- Creating for recognition

- Following the rules

- Conforming

- Caring what others think of my work

Once I learned to “let go” of all of these bad habits and insecurities, my Vision was set free. It was no longer constrained by rules, expectations or dishonest motives. It was such a great feeling to know that I could do anything that I wanted, nothing or no one could hold me back.

After finding my Vision and living with it for a while, I came to conclude that Vision has little to do with photography or art, but has more to do with being a well-adjusted, confident and independent human being. Once I had the confidence to pursue my art on my terms, I was free to pursue my Vision without fear of rejection or need for acceptance.

Something else I learned about Vision: it is not a look or a style. It does not force you to focus on one subject or genre and following your Vision will not make all your work look the same.

Vision gives you the freedom to pursue any subject, create in any style and do anything that you want.

Lone Man No. 35

Wanting More Than Winning Ribbons and Earning Likes

I talked about how winning was increasingly leaving me with this empty and hollow feeling. The problem I concluded, were my motives. I wasn’t creating for myself, but rather I was creating for validation, accolades and wins.

When I created for accolades, my motives were not “honest” because I was creating for the wrong reasons. And when I created for other’s approval, the images were not really mine.

I wanted to love my work even if other people did not. I wanted my opinion of my images to be the only one that mattered.

Learning to do this was hard and uncomfortable work, it required me to honestly evaluate my motives. At one point I asked myself this question:

If I had to choose between creating images that I loved,

or images that sold and won accolades, which would I choose?

It was really, really hard to be completely honest with myself, and it still is. I love the win, the attention, the likes…but if that is the reason why I create, then my work will not fulfill me and it will fail to convey conviction to the viewer.

The Road to Nowhere No. 1

Sometimes I still create dishonest images, and each time I see them I feel a pang of guilt. The Road to Nowhere No. 1 (above) is one such image (but that’s a story for a future article).

Conclusion

What I’ve learned and believe is:

- We all have the ability to be creative, even the biggest, nerdiest, technical photo nut among us. Even those who insist they are not creative. Even those who have just read this article and still insist they are not creative.

- We all have a Vision, in fact you cannot not have a Vision. Vision is simply how you see the world when you strip away all of your Vision Blockers.

- Creating images for yourself and images that you love will bring meaning and satisfaction to your photography that far outlasts accolades, wins and likes.

If you find yourself where I was 15 years ago, and you want more…then I’m here to tell you that it’s possible.

How do you get started? Try reading my article on ”

How I found My Vision ” for some ideas on how to proceed.

Cole

P.S. And after reading the article, please don’t write to tell me how much you disagree with Photographic Celibacy! I know, I know, I know

Five Simple Steps to Create Award Winning Images

You clicked on this link? Seriously, how gullible are you?

There are no simple steps or secret tips to creating a great image. If anything the title of this article should read:

5 Hard Things You Must Do To Create Images That YOU Love.

That’s the reality.

My goal is to create images that I love (not award winning images) and there are no set of rules, no camera, no magic settings, no new gadget, no plugin or secret technique that’s going to transform my work.

It takes hard work. It takes introspection. It takes persistence.

Since I tricked you into clicking on this link, I feel obligated to give you five tips. So here they are:

1. There are no simples steps!

It takes hard work to find and follow your Vision, to know what you love and then to single-mindedly pursue it.

2. A “great image” has little to do with your equipment.

Never has owning a prime lens, shooting at the optimal aperture or having a better camera made a poor image good or a good image great.

A friend and I were recently looking at one of Dorothea Lang’s images when we noticed that it was not very sharp. And yet that did not detract from the image. The image was powerful because of her Vision, not because of her equipment.

3. Don’t follow rules but rather see for yourself.

Rules are for people who have not yet found their Vision. Instead of following rules that will take you down the path millions of others are following, find your own Vision and create your own path!

Ansel Adams said “There are no rules for good photographs, there are only good photographs.“

4. Create for yourself!

Create an image that you love and don’t be concerned if others will like it. Don’t worry if your photo club expert “Herb” will like it and don’t be concerned if it will win a contest or get a lot of likes.

Care only what you think of the image and don’t worry how anyone else will receive it. You are not creating for them (at least you shouldn’t be).

5. Create an image and then be brutally honest with yourself about it.

Ask yourself:

Do I love this image?

What do I like or dislike about it?

What would I do differently next time?

Is this image good enough?

That last question, “is this image good enough” requires so much honesty! If the image isn’t quite up to snuff…then admit it, trash it and move on.

And PLEASE don’t ask other people these questions about your work, you must answer them for yourself and then work to improve. This is hard introspective work and you must do it over and over again.

________________________________

The next time you’re tempted to click on a link that offers a secret something, a simple something or a new something that will transform your work into award winning images…save your time and money and instead Find your Vision and work to create images that you really, really love.

Cole