Year: 2012

December 20, 2012

December 18th 2012 by Andrew S Gibson

This article is part of a series of interviews with long exposure photographers to celebrate the release of my ebook Slow. You can keep track of the interviews by clicking on the Long Exposure Photography Interviews link under Categories in the right-hand sidebar.

Cole Thompson is a fine art photographer based in Colorado in the United States. As part of the interview I asked him how, in a world where it seems that many photographers are producing similar work, it is possible to create original photography? His answer is worth reading, as it brings up one of Cole’s most interesting concepts, ‘photographic celibacy’.

Interview

How would you describe your photographic vision? What kind of look do you try and create in your photos?

I cannot describe my vision because I believe vision is intangible and indescribable. I view vision as the sum total of my life experiences. It is what makes me see the world a bit differently than another, because my experiences have been different.

I do not try to create a look or pursue a certain style in my images, I simply follow my vision. If you pursue a look, style or technique without vision, then those things are mere gimmicks and your images will lack power and conviction. I have been creating images since 1968 and so my skills would allow me to pursue many different styles or looks, but I’m only interested following my vision.

What I’ve learned is that vision must always come first and then techniques and style must flow from it. I’ve also learned that I must only create images that I love, that’s where my passion is and where my best work will come from.

Name three photographers you like and why.

Edward Weston is my photographic hero, not because of his images (although I do love them) but because of his attitudes. In my opinion Weston was a true artist and not a photographer (I draw a distinction between the two). He was independent in thought and did not care what others thought of his work. He created for himself and he had no obligation to explain his work to others.

One of my favourite stories is told by Ansel Adams on his first meeting Weston:

“After dinner, Albert (Bender) asked Edward to show his prints. They were the first work of such serious quality I had ever seen, but surprisingly I did not immediately understand or even like them; I thought them hard and mannered. Edward never gave the impression that he expected anyone to like his work. His prints were what they were. He gave no explanations; in creating them his obligation to the viewer was completed.”

In so many ways Weston has been my mentor. I re-read his Day Books every year and often read them just before I go out to create new images. His independence and obligation to self has inspired me.

Wynn Bullock. As a 14 year old boy I taught myself photography and part of what I did was to sit for hours looking at the work of photographers. Wynn Bullock was one whose work I admired and it wasn’t until years later I realised how much he and I saw alike, with both of us gravitating towards dark and contrasty images.

Ansel Adams. For many years I dreamed of being the next Ansel Adams (like millions of other young photographers). And for years I tried to imitate his look and even specific images. But then something happened to me that changed my attitude and led me on my quest to find my own vision. I was at a portfolio review and a gallery owner quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back towards me and said “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I proudly told him that I was because I loved his work! He then said something that really made me mad at the time, but later opened my eyes, he said:

“Ansel has already done Ansel and you’re not going to do him better. What can you create that demonstrates your vision?”

That was the beginning of the search for my vision. I still love Ansel Adam’s work, but I no longer want to be known as the “best Ansel Adams imitator in the world.” In fact, now if someone says to me “your work reminds me of Ansel Adams” I know that I have failed to distinguish myself with my own vision.

Long exposure photography – what’s the attraction and why do you do it?

The long exposure is not something I set out to pursue nor is it a marketing strategy I chose to become known as “the guy who uses long exposures.” But rather it’s the outcome from following my vision: it’s what I love, it’s how I feel and it’s how I see the world.

About 90% of my recent work was created using long exposures. I initially started off with water, then moved to clouds and now have been creating images of people with it as well. I suspect I’ll find other areas in which to use it as well.

Why black and white – what is the appeal for you?

That is a very difficult question to answer and perhaps my artist statement says it best:

I am often asked, “Why black and white?”

I think it’s because I grew up in a black-and-white world.

Television, movies and the news were all in black and white.

My childhood heroes were in black and white and even the nation was segregated into black and white.

Perhaps my images are an extension of the world in which I grew up.

I really don’t worry too much about the “why” behind things, I simply accept them as they are. I love black and white and always have. I’ve tried dabbling in colour and I’ve seen a few colour images that I’m drawn to, but in the end I really am just a black and white guy and I’m okay with that.

I can see from your portfolio that you are widely travelled, especially within the United States. How important is the contribution of travel to developing your portfolio from an artistic point of view? How has travel helped you develop as a person?

Travel is not critical for me in terms of subject matter, I can create similar images anywhere. But in terms of concentration and freeing my mind of my daily responsibilities, it is very important to get away. I have a full time job, a large family and many professional responsibilities, and I find that it’s difficult for me to concentrate when I’m on my home turf. However when I get away I’m able to leave all those things behind me. The best thing about being away is that I’m able to focus on just one thing: creating.

So travel has become very important for me. Many of these trips are to visit my children who have been stationed around the world. We visited my Marine Corp son who was stationed in Japan, my Peace Corp son in Ukraine and Poland and next year I’ll visit a son in Russia and Croatia. I am very fortunate to have family in these places because I probably wouldn’t have been brave enough to venture there without them. However next year will be a first for me as I visit Iceland by myself.

I do also travel within the United States. I go to Death Valley every January, the Oregon coast every September and I’m looking to add a third location, probably Hawaii. I like going back to the same spot each year because I can continue working on an idea, but once I’ve lost interest in that idea, I find a new location.

There are so many photographers working with long exposure photography techniques in black and white that sometimes it is hard to be original. Yet your work is very original. Can you give our readers any tips for finding an original approach to long exposure photography?

One of the side effects of the internet is that everyone quickly knows what everyone else is doing. When someone creates a new look, it seems as if overnight everyone is copying that look. I did that for many years, imitate others look, until I realised that I wanted to be more than an imitator or copycat. I want to create my own unique work and that is what I focus on, ignoring what others are doing.

I have a friend who thinks the key to success is to photograph something that nobody else has photographed before. He once told me that he had discovered something unique: frozen chickens. He said that he would always have a frozen chicken in his images (to this day I’m not certain if he was kidding or not!). In my opinion success is not about finding a subject that’s not been photographed before (I doubt there are many such things) but rather creating something unique, from your own vision.

I never focus what others are doing, I simply go down my own path. I am unaware what others are creating because I practice something that I call Photographic Celibacy. It’s the practice of not looking at or studying the work of other photographers. I do this to reduce the number of images floating about in my head and to reduce their influence on my own work. I find that when I see a great image, my first thought is “how can I do that?” Then I catch myself and remember that I do not want to imitate, but create. I’ve practicing Photographic Celibacy for five years now and it has been very helpful, but I still have some iconic images floating around in my head and when I go to the grocery store I have to admit that I still look at the bell peppers! But I’m doing better at not imitating others.

Most people who hear about this practice think I’m crazy, they believe that imitation is how we build our skills and grow creatively. I disagree, I believe imitation is harmful because it retards the development of our own vision.

Can you tell us a little about The Lone Man series? What inspired it? What are you trying to express with these images?

Like most of my series, the Lone Man was an idea that I just stumbled upon and spontaneously created. Whenever I get an idea for a new project, I write it down on a long list. However the truth is that I’ve never once used one of those ideas, all of the ideas for my portfolios have been spontaneous and just took off like a wildfire.

That’s what happened with the Lone Man series. I was in North Laguna at one of my favourite dive spots, creating long exposures of the water. It was a pretty crowded day at the beach and so people were out on the rocks looking for creatures in the tide pools. A group of people were in my shot and I was impatiently waiting for them to leave. While waiting I decided to do a test exposure so that I’d be all ready as soon as they left. After the 30 second test exposure, I noticed that one of the people had stood still for the entire 30 seconds and I recognised his body language. It was pensive, thoughtful and you could tell the man was thinking about things larger than himself.

Soon I started noticing this effect in a lot of people, they would come to the edge of the world and just stare off into the distance. I began photographing these people and the Lone Man series was born. Here is the artist statement for this series:

Something unusual happens when a person stands on the edge of the world and stares outward. They become very still and you can almost see their thoughts as they ponder things much greater than themselves:

Where did I come from?

What is my purpose?

What does it all mean?

What is beyond, the beyond?

Do I make a difference?

Is there more?

At that moment they are The Lone Man, alone with their questions and thoughts about life, the universe and beyond. People are affected by this time of meditation and they often vow to make changes in their lives. But this moment is short lived as these weighty thoughts are replaced with more immediate concerns:

Should I eat at McDonalds or Burger King and should I try that new green milkshake?

Normally I do not comment on what my images mean, sometimes because they are just beautiful images and don’t have any deeper meaning, and often because I think it’s the viewer’s job to decide what they mean. But in the case of The Lone Man, I have revealed a bit of what I’m thinking about in my artist statement. When I was creating these images I was impressed at how standing at the edge of the world causes people to ponder their smallness and their purpose in life.

So many people have asked me “how did you get those people to stand still for 30 seconds” and “did you ask them to stand still?” I didn’t have to ask people to stand still because this is just what people do! You could see them deep in thought as they stood there, often for several minutes, and pondering the “bigger questions” of life.

The last part of my artist statement is a little dig, at how little time we spend thinking about those bigger issues and how easily we are brought back to our own petty concerns; my burger wasn’t cooked right, I don’t get a good cell signal at my house, the guy in front of me is driving so slow etc. So much of what we concern ourselves with is so unimportant in the larger scheme of things.

Another series I like is Monoliths. What draws you to photographing seascapes? What’s the appeal of the giant rocks that appear in these photos?

I grew up in Southern California and spend my youth at the Huntington Beach pier, bodysurfing at lifeguard tower number 1. I spent countless hours diving Laguna, La Jolla and Catalina. The ocean was a large part of my life until I moved to Colorado in 1993. Truthfully the ocean is the only thing I miss about California and whenever I visit, I am drawn back to it.

Photographing the movement of the ocean with long exposure is just a part of my vision, it’s how I see the ocean. To photograph it with a static image, seems to me a sin!

I have always had a “thing” about Monoliths, first when I was a young boy and read Thor Heyerdahl’s “Aku-Aku, the Secret of Easter Island.” Those stone giants really captured my imagination and I wondered who created them, how and why?

Next I was fascinated with the Monolith in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” And so when I first saw the beaches of Bandon, Oregon with their statuesque “monoliths” (sea stacks to the locals) all of my past fascinations flooded back and I knew that I would photograph them. I am certain they have been photographed a million times before, but since I don’t look at others work, I am ignorant of how others have portrayed them. Even if I were to find out that I had unknowingly created images similar to others, it would not concern me, as my images are honest creations borne from my vision.

Perhaps related is your series Ancient Stones. What is the story behind these photos? What is significant about these stones, and where did you get the idea of photographing them?

The Ancient Stones series is related to the Monoliths in sense. I was wandering about in Joshua Tree, waiting for inspiration to hit me, and nothing was happening. In response to those “dry spells” I’ll usually find a nice spot to sit for a while, clearing my mind of clutter and trying to see more clearly. As I sat there looking at those large rocks, I had some thoughts that were similar to what I was thinking when looking at the monoliths in Bandon. How long have these rocks been here, millions of years? How many men have they seen scurrying about, going here and there, building this and that, full of self importance? I wonder if “they” find all of this amusing?

That made me want to photograph “them” in a way that showed their permanence and timelessness. I hoped the long exposure helped do that, contrasting the still stones against the movement in the sky. I’ve only just started this project and so I’m not sure where it will go from here.

I believe you earn a living, or at least a part-time living, as a fine art photographer. Do you have any advice for our readers on how they can work towards achieving the same goal? What can they do from an artistic viewpoint to improve their work and a practical viewpoint to selling their work?

I have a full time job and do not earn my living from my art. Many years ago I purposely chose not to pursue photography for my living because I feared it would take the fun out of it, and I’ve never regretted that decision. I create only for the pure love of it and am proud to be an “amateur” in the truest sense: I am self taught, I create for myself and I do not earn my living from my work.

What I dislike about earning a living from your art is that it invariably involves compromises and I never want to create for others. I want to create whatever and however I want, not caring if a single person likes my work. Ironically it is that independence that brings out your best work and may bring about success. I once posted on my blog that the fastest way to earn money from your photography is to sell your equipment. There is truth in that!

Links

Cole Thompson’s website

Cole Thompson’s blog

You can contact Cole by email at Cole@ColeThompsonPhotography.com

Photo Gallery

Here are some more of Cole’s long exposure photos:

December 3, 2012

Story Number One:

I was 16 years old and living in Anaheim California. I had this idea for an image, a gull flying against a clouded moon, but I couldn’t find a way to create the image with a single shot. So I decided to combine two images, not as a double exposure captured in-camera, but by combining two images in the darkroom. Composites are easily done in today’s digital world, but they were not easily done back in 1970. Back in the “old days” I would sandwich the two negatives together in the enlarger and project them as a single image.

The first image was taken at night in the local K-Mart parking lot. I took a series of shots with clouds floating past the moon. I had this idea (vision) in my head of what the final image would look like and so I placed the moon and clouds on the right and left room for the sea gull on the left. The shot of the sea gull was taken later during the daytime in my high school parking lot, I shot a series of gulls looking straight up. Working from memory of where I had placed the moon and cloud in the frame, I positioned the gull on the left.

After I processed the negatives, I had to find two images that would work together, not just in terms of composition but also exposure. Getting a good print with this method is a challenge since you have two negatives that may have different printing needs, but you must print them together as one.

I named the image “Gull and Moon” and while I loved the composition, I was never able to get the blacks that I envisioned, the print was very muddy.

Story Number Two:

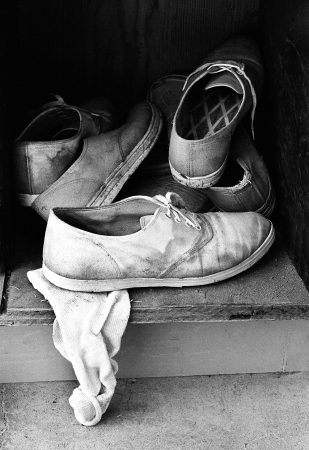

I was new to Loara High School and had joined the Yearbook staff as a photographer. The new yearbook advisor was John Holland the photography teacher, he became and remained a friend and mentor until last year when he passed away. What was so very different about John was that he encouraged us to create fine art images for the yearbook, not just pictures of the football players, cheerleaders and cheesecake shots. This was fun (!) and we had a wonderful time creating artistic images for the yearbook including my “Shoes” (above) which was prominently featured.

Unfortunately neither John nor any of us really stopped to consider why people purchased yearbooks. It was not for fine art images but for the pictures of the football players, cheerleaders and cheesecake shots! When the yearbooks arrived and were being handed out there was a near riot as the football players angrily confronted the yearbook staff. I was a junior (and small for my age) and I remember slowly slinking out through the back of the crowd and hiding in the photography room. I made myself scarce for several days.

Story Number Three:

After high school and for 30 years after, I focused on family and career and neglected my photography. During those years we moved several times and with each move I threw out more and more old things, including much of my photography. When I returned to photography around 2004 I wanted to feature some of my earlier work on my website and I began searching for anything that might have survived.

Most of my negatives were gone and only a few prints survived, in fact only 13 remained from all those years of work. Most of these images survived only because a single print was still around, and this was the case with “Mary at Corona.” I found a single 8 x 10, poorly printed and curled up print. This has always been a special image to me and I so set about the task of restoring it.

I scanned the image and worked on it in Photoshop. I was pleasantly surprised because not only was I able to restore the image, but I was able to bring it into compliance with my original vision, something I was never able to do in the darkroom! Just tonight I was comparing the original to the restored version and it reminded me of why I love digital.

If you are interested, you can see those restored images from my early years here: https://colethompsonphotography.com/portfolios/collections/1970s/

Recounting the story behind this image reminded me of the many lessons that I learned from this experience.

- Vision is the most important ingredient of a great image.

- Yearbooks are for documentary work, not fine art photography.

- Focus on the creative early on, it’s more important than the technical which can be learned quite easily.

- Don’t throw things away when you are young, you’ll regret it later.

- If you have an image that you cannot get just right, keep working on it.

November 2, 2012

I just spent the most wonderful five days in the San Francisco area. I was warmly received by the Palo Alto Camera Club and then spent some time in the City where my wife and I enjoyed the sights and some fantastic food. Then we spent a day walking on and around the Golden Gate Bridge with spectacularly perfect weather.

While on the bridge I spied this Monolith which I wanted to photograph. I spent several hours trying to find a vantage point where I could photograph it alone, separated from the city. However due to a restricted area under the bridge, I was unable to find such a shot and gave up. But I’ve learned that when the ideal conditions do not exist, you should look for other opportunities in the non-ideal conditions.

Instead of photographing this Monolith alone as I had done with all of the other images (https://colethompsonphotography.com/portfolios/series/monoliths/) I decided to include a man made structure to show the contrast between the two.

I like how the contrast between nature and man works in this image to make it stronger.

Cole

October 20, 2012

Many people assume that I’m working in film and others are surprised to learn that I photograph in color. Let me explain.

All of the work you see on my website (with the exception of the 1970’s portfolio) was created digitally. I switched to digital in 2004 after working 35 years in the darkroom. And I’ll be honest, while I have fond memories of those darkroom days, I do not miss them and I would not go back.

Why? Because my work is better since I began using digital.

I’ve often heard the assumption that digital is suitable for color but not for black and white. That has not been my experience. I’ll use whatever tools give me the results I’m looking for and I have absolutely no allegiance to the process; film is not sacred, digital is not sacred, old processes are not sacred…the only thing that is sacred to me is the image.

Perhaps more surprising to some is that I shoot all of my images in color. I’ve written that I shoot in B&W mode and so you might wonder how can that be? Shooting in B&W mode allows me to see the camera’s preview image in black and white, but I save my files in RAW which means they are really in color.

Confusing? When you shoot in RAW all of those settings such as B&W mode, sharpness, saturation, toning, color balance…are not recorded in the image. RAW means just that, it’s a raw capture without any of those tweaks and the image is recorded in color.

This is a wonderful thing! This combination of B&W mode and RAW allows me to preview the image in black and white but process from the color image. Why do that? Because I don’t want my camera or software to decide how my images should look in black and white, the black and white processing is what makes my images “mine!”

Sometimes I’ll show people the “before” color photograph to illustrate how my vision and processing has changed the image.

My vision drives my processing and I’ll happily use whatever tools and processes best helps me do that.

Cole

October 4, 2012

Recently a friend told me of her frustrations as she sought to find her Vision and this brought back memories of my own journey. For years I was confused as to what Vision was and frustrated because I didn’t know how to find mine.

I had absolutely no idea how to find my Vision. I was told that I had to keep working at it, but how? It was frustrating because it was such a nebulous concept and I had no idea how to proceed.

And the truth was that I wasn’t sure that I was capable of having Vision. I was raised in a home where the arts were not emphasized and I never developed creative skills; instead I was logical, methodical and gravitated towards mechanical things. I wondered if some people were just naturally creative and others were not, and feared that I was in the “not” category.

The good news is that not only did I find my Vision but I am absolutely convinced that everyone has one. It may be buried deep under a lot of “stuff” and it may be atrophied from lack of use, but it is there and you can find it.

What is Vision? It is the sum total of my life experiences that makes me see the world in a particular way. Because my experiences are different than yours, my Vision will be different than yours. And since my Vision is based on my experiences, it will change with time.

Vision is what makes me see an image that others may not see, or see it differently. Have you viewed a great image that was created where you had photographed before? I used to wonder why someone else could see that image and I could not, I believe it’s because we have different Visions. The good news is that it works both ways and sometimes you’ll see an image where others do not. The important point is that you should pursue your Vision and not try to see what others see.

Because Vision is simply your experiences and how you see life, I am convinced that everyone has one. It just needs to be discovered. Sometimes that is hard because it can be buried beneath a lot of “stuff” such as self doubt and a lack of creative experience, as was in my case. But I found mine and am absolutely convinced that each person is capable of finding theirs too.

So how did I go about finding my own vision? I had this idea that to follow my Vision was synonymous with following my heart and so I took all of my images and divided them into two piles; ones that I REALLY loved and everything else. I purposely ignored “good” images or ones that others liked and ones that sold the best because I didn’t want to consider what others thought, I only wanted to consider what I thought.

Then I started studying those images to understand what they had in common. I noticed that when I was doing what I loved and pleasing myself, my images had a particular look and mood. I also noticed that what I was photographing and how I was photographing was changing; I was moving away from my landscape roots and creating a different kind of work.

Once I found my Vision, there was still a challenge, and that was to religiously follow it. I was so used to copying others, pleasing others and following trends that I had to train myself to only pursue images that followed my Vision. When you copy others, the best you can ever hope to achieve is being a great imitator. When you seek to please others, you end up not pleasing yourself. When you follow trends, you are like the blowing grasses which are buffeted by every wind. Following your Vision is the only way to achieve satisfaction.

Over the course of two years (it was a slow and painful process) I found my Vision. It was not a “Eureka!” moment, but rather it crept up on me slowly until one day I just realized that I had one. I cannot put my Vision into words, but now I understand it and what was once so mysterious now seems so simple.

Finding my Vision gave me a tremendous feeling of freedom and confidence. I no longer felt constrained or bound by the opinions of others, I was free to create what I wanted and how I wanted, regardless of who liked it. The most important thing was that I was happy with my work. Finding your vision does not guarantee critical or financial success, but it will bring about personal satisfaction. Ironically, as I stopped caring what others thought and created for myself, my work became more popular with others.

Vision is more important than your equipment, your location or your processing techniques. Vision is the most important ingredient in a great image and I am absolutely convinced that everyone can find theirs.

Cole

September 20, 2012

I’m back from my annual retreat in Bandon, Oregon. It’s a very small town and I think it’s the most beautiful and unique spot on the entire Oregon coast. I go there each year for about 10 days to photograph, to be alone and to contemplate. I found some wonderful new dunes on this trip and the Gods of wind and weather smiled favorably upon me. Here is a new “Dunes of Nude” image I created while on this trip.

~

I mentioned that one of the reasons I go to Bandon each year is to be alone and think. Here are some of the thoughts I had while on this trip:

- It’s amazing that birds can fly.

- Driving alone for miles on the beach is great fun.

- Life is very short. The older you get, the shorter it seems.

- Fog can come in very, very quickly.

- I don’t trust people who don’t like dogs.

- As much as I love photography, I’m not sure how important it is in the larger scheme of things.

- Why do we spend so much of our lives caring what others think?

- Halibut fish and chips; much more expensive than Cod, but worth it.

- Teenage daughters are difficult to understand.

- Two “thumbs up!” to El Sombrero in Coos Bay, Oregon.

~

Yesterday I had my interview with Brooks Jensen for LensWork Extended. It’s always nice to talk with Brooks because he’s so down to earth and pragmatic. But in truth I always feel intimidated because of my lack of knowledge of art and “art talk.” I am unschooled in such things and simply know what I like.

~

Tomorrow (Saturday) I’m off on another trip and hope to see some new images. I say “see” because I know the images are there, it really is just a matter of being able to see them!

Aloha.

September 7, 2012

![]()

Zocalo Public Square recently hosted a discussion on “Idea Theft” and asked me to participate.

Up for Discussion

Theft Is In the Eye Of the Beholder

When Is It OK For Someone in Your Field To ‘Steal’ an Idea?

Did Samsung violate Apple’s intellectual property rights by making a phone with a pinchable screen? Should one-click online ordering be an idea owned by one corporation? Should the day come when Mickey Mouse belongs to everyone? Can Chinese companies make shoes featuring a swoosh? At what point would our paraphrasing of someone else’s paraphrasing of what someone else said amount to plagiarism?

Our culture, our laws and our technologies are all grappling these days with the meaning of intellectual property and the boundaries between improving upon past innovations, and misappropriating them. In advance of the Zócalo event “Does Imitation Breed Innovation?” we asked five artistic minds to ponder when it’s OK for someone to steal an idea.

The case for artistic celibacy

Most of us would never steal an object…but the issue is not so simple or clear when we’re talking about something as intangible as an idea, especially in art. If someone were to copy an image from the Internet and put their name on it, we’d all call that stealing. But what if someone creates an image that uses a similar look, style, technique or subject matter to mine…would that be stealing? And what if upon investigation I found that the other artist’s work had pre-dated mine or that they were unaware of my work?

This has happened to me several times. Sometimes the work had been developed in parallel, with each of us unaware of the other’s work. Sometimes the other person’s work had pre-dated mine, and sometimes people loved my idea and were simply imitating it. All art is evolutionary, some say, built upon the work that comes before.

Ultimately I came to the conclusion that I cannot determine the difference between stealing, copying, imitating, working in parallel or building upon another’s work. Most importantly, I shouldn’t care! As an artist I need to stay focused on what I am doing and not what others are doing. Not only would that be a waste of time, it would take energy and focus away from my art. My job as an artist is to create as uniquely as possible and I personally do not wish to build upon the work of others.

To facilitate seeing uniquely, I have been practicing “Photographic Celibacy” for the last five years. It is the practice of not looking at other photographers’ work. I do this to minimize the influence others have on my art and to reduce my temptation to “copy” them. I personally find the unconscious inclination to imitate to be destructive to the creative process.

Cole Thompson is a black-and-white fine art photographer living on a small ranch in Northern Colorado. He began creating at age 14 and has always worked in black and white. He is often asked, “Why black and white?” His answer: “I think it’s because I grew up in a black-and-white world. Television, movies and the news were all in black and white. My heroes were in black and white and even the nation was segregated into black and white. My images are an extension of the world in which I grew up.”

—————————————————————————————————————

How can you not copy a classic drink?

It’s never acceptable to take from another and claim it as your own, although in the tight-knit fraternity of cocktail mixing, ideas and past traditions are widely celebrated and emulated.

Today it is en vogue to be a bartender. However, for a long time bartending was not considered to be a professional end goal. In fact we had been considered downright disreputable. That’s one reason we celebrate those who came before us, who taught us everything we know and inspire us to be better and question the received wisdom. This questioning spawns conversation or variations. The same thing is done in literature, for example when James Joyce wrote Ulysses he wasn’t stealing from the Odyssey but rather having a conversation with Homer.

We too are storytellers but with drinks. When we make a variation of a classic and don’t tell the story behind the drink we rob our guests of a rich and enduring connection that they can in turn share with others. I am no different than you when I walk into a bar. When it is a bar manned by someone I like and respect, I am filled with an excitement that borders on mania. I feel the same way every time I make a drink I love, I can’t help but tell the story of that drink and when I slide it over to my guest in my mind there is diffused lighting and Teddy Pendergrass playing because that is love.

Zahra Bates is head bartender at Providence Restaurant.

—————————————————————————————————————

True stealing is better than borrowing

It depends what’s meant by the word “steal.” It’s never OK for someone to literally steal something, however the question usually isn’t one to take literally. An idea itself isn’t what’s valuable. It’s how the idea is implemented that creates value.

In Web design, as in any industry with a creative component, people copy each other’s ideas all the time. Sometimes these ideas have become so much a part of the standard or the convention that not using them would lead to a less effective design. For example, most people expect to arrive at a website and find a list of links across the top or down the side that serves as global navigation. On the other hand, exactly how one designer crafts a navigation bar isn’t part of that convention.

There’s a famous quote attributed variously to Picasso, Stravinsky and others, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal,” which is often misunderstood, but applies well to this question. When you borrow something, it’s not yours. You plan to give it back. When you steal something, you make it yours. It’s this notion of making it yours that’s the important part of the quote.

The proper way to steal an idea in design or any industry is to make it your own. Take it apart. Understand what makes it a good idea. Assimilate it and internalize it. Mix it with all the other ideas within you. Something new will arise from the combination of the ideas within and the idea you’ve stolen.

That new idea may recognizably come from the idea you’ve stolen, but it won’t be the same. It will be improved. It will be different. It will be something of your own. When you steal ideas in this way you add to them and contribute to your industry. If all you do is copy them outright you’ve only taken something that doesn’t belong to you.

Steven Bradley is a web designer and WordPress developer who moved to Boulder, Colorado to be near the mountains. He blogs at Vanseo Design and owns and operates a small business forumhelping people learn how to run and market their business more effectively.

—————————————————————————————————————

Fashion, the ultimate minefield

I work as a professional fashion illustrator. I am also an enthusiastic, non-professional fashion blogger. Of these occupations, illustration is more clearly governed by law when it comes to intellectual property. Although I’ve discovered that explaining the nuances of copyright to clients unfamiliar with the concept is so confusing in the digital age, the conversation can be counterproductive to developing relationships and doing business. This means that my business is often run more on intuition and good faith than on contract. As an illustrator who works in the fashion industry, my laissez-faire approach to enforcing my own copyright would horrify illustrators who work in traditional publishing. But, with my limited time on Earth, I’d rather draw than practice the law.

Fashion blogging is a virtual Canal Street of grey-market intellectual property violation. A lot of this is lazy blogging—just appropriating other people’s creations. Then there are a few clever bloggers who are combining images and ideas in startling new ways, creating a fascinating and viral universal cultural pulse.

When is it not OK to take an idea? That may be the more interesting question. I believe the answer relates to power dynamics. When a wealthy corporation profits off the idea of an independent creative, something feels unjust about that. But if a teenager somewhere throws an appropriated image up on their Tumblr, logging it into the stream of consciousness of modern youth, throwing the book at them just seems petty… and old-fashioned.

Danielle Meder is a fashion illustrator. She blogs at Final Fashion.

—————————————————————————————————————

Ideas can’t be locked up

“A great artist never borrows; he steals.” Variations on this insinuatingly provocative quip have been ascribed to so many artists—including Balanchine and Stravinksy, to name only two prominent figures in my field, which is dance—that it is impossible to know who originated it. The remark itself appears to have been borrowed—or stolen—multiple times. The point: that an idea completely appropriated, digested, and re-presented by an artist is not merely borrowed but transformed, and therefore rightly owned. If that is true, then stealing is always acceptable—and a prerogative of greatness.

The problem of “stealing” arises only when an aggrieved artist alleges that this taking-and-changing process has been insufficiently transformative, especially when there is prestige, career advantage, or, above all, serious money involved. Anxieties over influencing versus being influenced are sharpened to the point of drawing blood when more than a given instance of influence per se lies at stake. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery only until someone else is getting royalties—or selling at auction prices—you think rightly yours.

Artists of the past would find our modern attitude to ownership of ideas strange, to say the least. In Shakespeare’s day, for example, the notion barely existed, if at all. If Shakespeare were our contemporary, he would likely find himself embroiled in a lawsuit for copyright infringement with the chronicler Hollinshed, whose prose the playwright rather openly pillaged. In the words of one scholar, passages of several of Shakespeare’s history plays are more or less metrical transcriptions of Hollinshed into blank iambic pentameter. If that isn’t stealing, what is?

Of course, few would argue that the body of law that attempts to define intellectual property and copyright of artistic production should be abolished altogether. Nonetheless, if only for the sake of intellectual honesty and good faith, we ought to acknowledge how dubious, if not self-contradictory, it is to attempt somehow to define the expression of an idea (which is intrinsically protected by copyright) apart from an idea itself (which is not protected)—the key distinction that undergirds the whole legal apparatus.

In fact, the single most powerful driver behind the series of extensions of copyright beyond the death of the author has been the Walt Disney company, a corporate behemoth which has successfully pressured the US government to prevent Mickey Mouse from dancing into the public domain—Mickey, who, at his birth in 1928, really was a character, but who has long been reduced (or elevated) to the status of brand identity, corporate icon, and so on.

Ultimately, the whole concept of intellectual “property” that underlies the possibility of one artist’s accusing another of “stealing” an idea is rooted in the bourgeois attitude towards knowledge—which is entirely intangible—as a kind of thing. (I mean bourgeois in the historical sense of term, not, as the word is usually used vernacularly in the U.S., as a mere hip insult). The finer the distinctions made in any given lawsuit, the more a detached viewer may see the concerted attempts involved to shore up a giant castle built of sand. For ideas are not, and never really can be, things.

The deepest fear that flows beneath the whole discussion is not the fear of being insufficiently original, or of having our ideas stolen, or of some other artist’s making money that is rightfully ours. The immateriality of all mental activity, including all acts of artistic creation, is what terrifies and appalls and makes us all a little bit desperate. Ideas, ultimately, cannot be owned, borrowed, or stolen—and you can’t take them with you. What we really fear when we admit that we are afraid of having our ideas stolen is death: the howling, unimaginable silence that will ultimately engulf all we do or have ever done.

Christopher Caines is artistic director of Christopher Caines Dance. His most recently published writing is a commissioned essay on Antony Tudor for the Dance Heritage Coalition’s America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures online project. Upcoming performances include his company’s appearance at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City for the Feast of St. Francis/The Blessing of the Animals on October 7.

*Photo courtesy of cangaroojack. Photo of Danielle Meder courtesy of Matthieu Da Cruz.

August 31, 2012

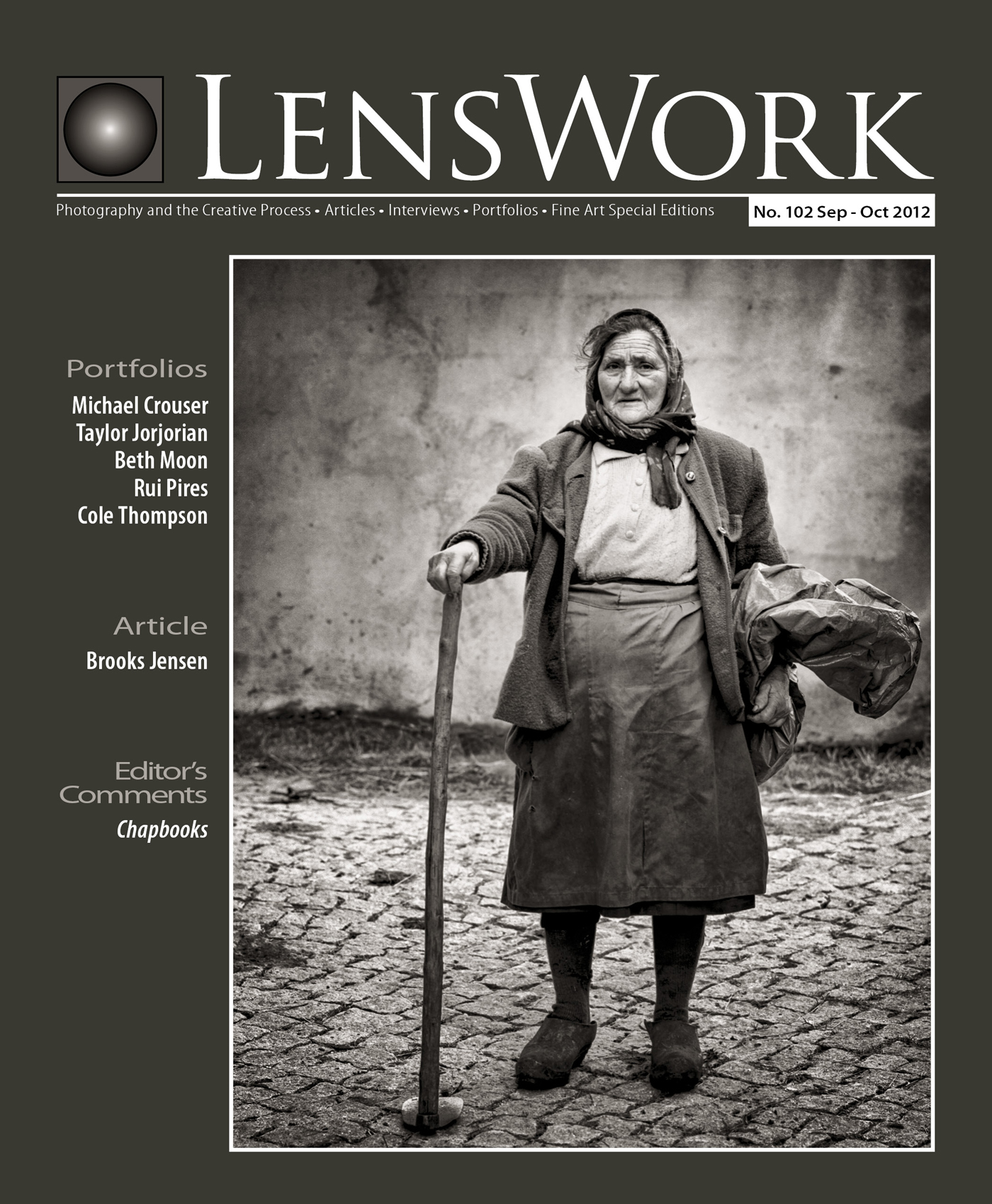

My portfolio “Death Valley: Where Time Stands Still” is featured in the current issue of LensWork. It is always an honor to be featured here.

If you’ve never seen a printed copy of LensWork, then you are missing out on one of the finest printed publications in the world. The quality of their duotone printing surpasses most of the photo books I own and the quality of their featured photographers is consistently high. And then there is LensWork Extended, a DVD with additional content such as audio interviews, additional images, video and even…dare I utter the word…color!

Something else I love about LensWork are the writings of editor Brooks Jensen. I have always liked his out-of-the-mainstream views and appreciated his common-sense wisdom about art and photography (even though we differ in opinion on “Photographic Celibacy!“)

So far I have had these portfolios featured in LensWork and LensWork Extended:

- Grain Silos

- Ceiling Lamps

- The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau

- Death Valley: Where Time Stands Still

Unfortunately you can no longer purchase LensWork on the newsstands, however you can purchase a copy or subscribe here:

http://www.lenswork.com/previewpages/lw102/lw102preview.html

If you were going to read just one photo publication, I’d suggest that you get rid of the ones that focus on equipment and subscribe to LensWork that focuses on art. At $39 a year, it is a steal and I’m not sure how Brooks Jensen can afford to do it!

Cole

August 23, 2012

Here’s a new video featuring my Death Valley images. They will be appearing somewhere special in the near future.

Here’s a hint; it’s a black and white publication.

Cole

August 17, 2012

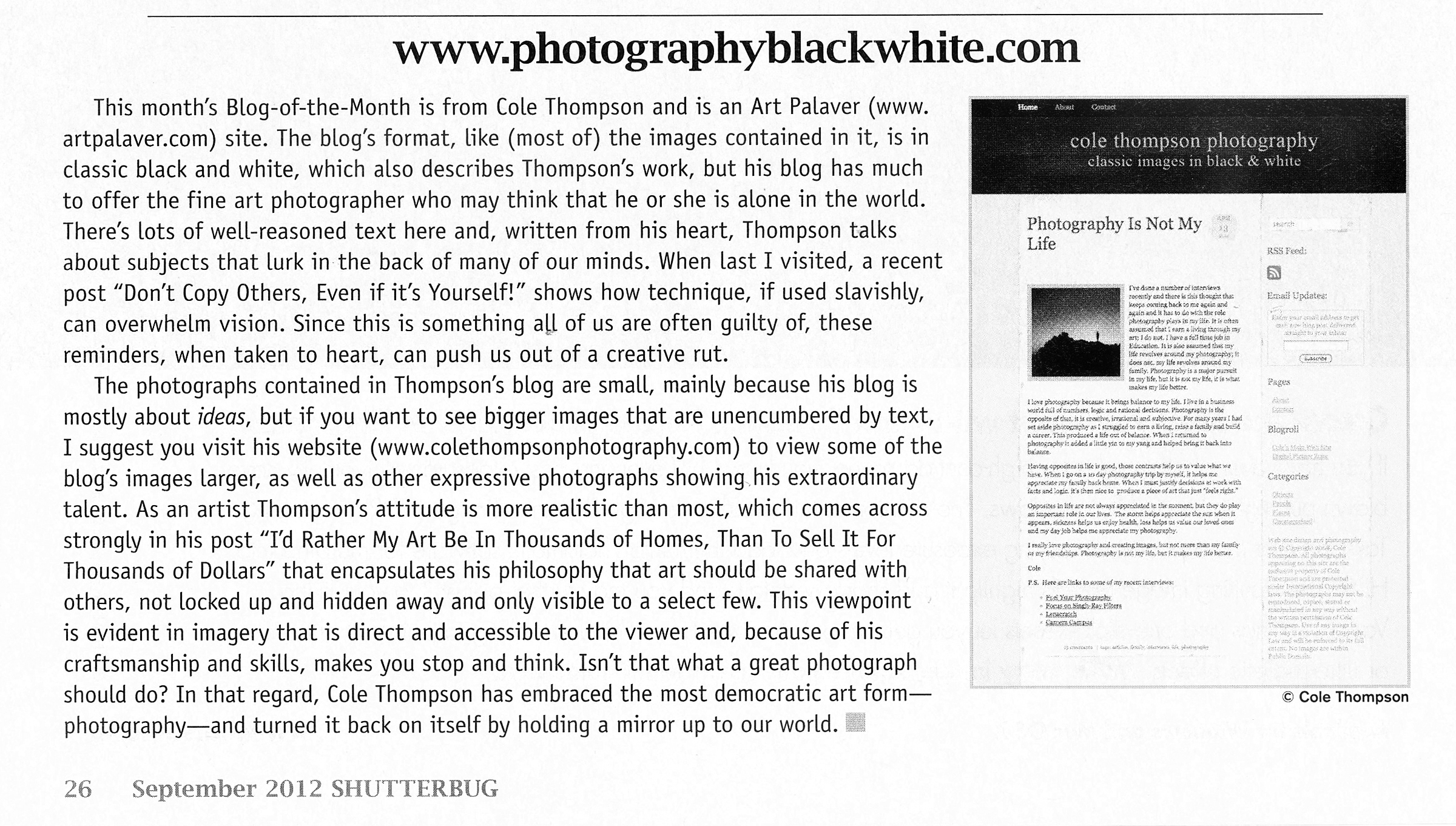

Joe Farace writes a column for SHUTTERBUG. I knew I was going to like Joe’s views and attitude when I saw this tag line:

“Ultimately, it’s all about the image…”

You can visit Shutterbug at http://www.shutterbug.com/

This month Joe introduces his readers to four new photographers, including myself and my blog.

Cole