Tag: photographic celibacy

March 22, 2018

It’s hard to believe that it’s been ten years since I first started practicing Photographic Celibacy. It’s hard to believe because I never thought that I would do this for so long. I figured that it would last for 3-4 years and then be done with it.

So what is Photographic Celibacy, why did I start this practice, why am I still doing it and what are my thoughts some ten years later?

First, the story on how Photographic Celibacy came to be.

The Wake-Up Call

A few years ago I was attending Review Santa Fe where over the course of a day my work was evaluated by a number of gallery owners, curators, publishers and “experts” in the field.

During the last review of a very long day, the reviewer quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back to me and said “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I replied that I was, because I loved his work! He then said something that would change my life:

“Ansel’s already done Ansel and you’re not going to do him any better. What can you create that shows your unique vision?”

Those words really stung, but the message did sink in: Was it my life’s ambition to be known as the world’s best Ansel Adams imitator? Had I no higher aspirations than that?

I desperately wanted to know if I had a Vision, but there was a huge problem: what exactly was Vision and how did I develop it?

What is Vision?

I found little help when searching the internet: I found several definitions of Vision, but none of them made any sense to me. Was it something you were born with? Was it something you could learn? Was it a style or look? Was it a talent that you developed? Could you go to photography or art school and gain it?

The Plan

I desperately wanted to know if I had a Vision, but the possibility of finding out was scary. What if I found out that I didn’t have one…what did that mean for my photographic aspirations and future? Part of me didn’t want to find out (I figured it would be better to be mediocre and have hope rather than mediocre and have no hope). But after I got over the initial fear, I knew that I had to find the answer.

So I devised a plan to find my Vision. I created a list of ten things that made sense to me, including:

I separated my work into two piles: work that I really loved and everything else. And then I tried to understand what it was about those images that made me love them.

I then committed to never again create images like those in the second pile. That included images that others loved, images that sold well and images that had won contests. It also meant that I would continue to create images even if no one else liked them, they didn’t win contests and didn’t sell…as long as I loved them.

I stopped listening to other people’s advice about my images. I figured if I was going to find MY Vision, I needed to stop listening to others no matter who they were, how accomplished they were or how successful they were. Their advice came from their experiences and point of view and not mine.

I needed to stop paying attention to what others thought about my work and so I stopped posting images on social media and entering contests. I was doing all of that for the validation, because I lacked confidence in my work. Each time I got a like or won a contest, I saw that as evidence that my work must be good.

Photographic Celibacy

And I did one other thing, perhaps the most controversial and certainly the most significant: I stopped looking at the work of other photographers.

Why?

Because I felt that if I continued to immerse myself in the images of others, I would continue to create work that looked like theirs or was a derivative of theirs.

I wanted to create my own work, from my Vision. I wanted to see through my eyes and not through the eyes of those photographers whose work I spent hours and hours looking at.

Did It Work?

Did it work…did I find my Vision?

Yes!

As I stopped looking at other people’s images and focused on what I was creating and what I thought of my work, my Vision began to emerge. The work I am creating now is my work, not an imitation of someone else’s. Now that doesn’t guarantee that my work will be liked by others, will sell or win awards…but it does guarantee that I’ll love my work and have the satisfaction that comes from creating honest work.

Ten Years Later

Ten years later and I’m still practicing Photographic Celibacy because I find it a useful practice for two reasons: first I’m still inclined to copy other’s work

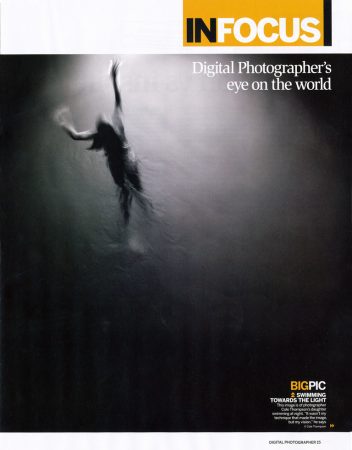

An example: a couple of years ago I had an image featured in the book “Why Photographs Work” by George Barr. When I looked through the book to find mine, I saw this wonderful image entitled “Three Crosses” by Brian Kosoff (above). I fell in love with the image, contacted Brian to purchase a print and hung it in my office to look at while I worked.

But then something began to happen, for the next several weeks I found myself driving around, looking at telephone poles so that I could create such an image. But then I remembered:

Ansel’s already done Ansel and Brian’s already done Brian.

And the other reason I still find Photographic Celibacy useful: it keep me focused on what I am doing and not what others are doing. When I look at the work of others I find myself comparing their images and successes to mine. Sometimes I get discouraged at the large number of great photographers out there and all of the great images being created. All of this is an unnecessary distraction that keeps me from my purpose: creating images from my Vision.

Staying focused is hard and even harder when you are looking and comparing yourself to others. As my mother used to say: what others are doing is none of your business!

Lessons Learned

Here is what have I learned in these ten years regarding Photographic Celibacy:

Photographic Celibacy may not be for everyone. When I first shared my views on Photographic Celibacy, they were not well received. About 75% of the people thought it was just a stupid idea (and many said so), about 20% understood but said it wasn’t for them and about 5% understood and pursued the practice. One thing I see more clearly now is that while this practice works for me, it may not be right for everyone. Perhaps others are not as influenced by other photographer’s work as I am, or perhaps they are but feel that Photographic Promiscuity is the best creative path for them.

Not everyone is seeking their Vision. I have come to recognize that not everyone wants to create from their Vision. For some, photography is simply a hobby that they enjoy, others are interested in documenting while others still are focused on the technical aspects of photography. If you’re not seeking your Vision, you should keep enjoying the work of others!

Celibacy may be appropriate at a certain point in a person’s creative development. I am more open to the idea that Photographic Celibacy may be a practice that is best applied at a certain point in a photographer’s creative development.

For me, this point came during a creative crisis: I desperately wanted to do more than imitate…I wanted to create images that were mine! I wanted this so badly that any sacrifice was worth this prize, even not looking at other photographer’s images.

Photographic Celibacy still serves a purpose, even ten years later. I always thought that once I had answered the question: do I have a Vision? that I would be able to go back to looking at images. But I discovered that the same forces that kept me from my Vision are still at work ten years later. And so, I believe that practicing Photographic Celibacy is as important for me today, as it was ten years ago.

Conclusion

So here I am ten years later, more committed than ever to Photographic Celibacy. Why? Because it works for me.

Will it work for you? Only you can answer that.

It has been one of the key ingredients of my success, which I define as creating images that are honestly mine and that I love.

Will I practice Photographic Celibacy forever? I don’t know, but I will for as long as it serves a useful purpose.

Cole

December 19, 2013

Balance No. 1

I recently taught a workshop on Vision and was discussing my practice of Photographic Celibacy. I explained that the reason I do not look at other photographer’s work is that I don’t want my Vision to be tainted by the vision and images of others. And while that is completely true, there is another reason that I am embarrassed to admit: when I look at other people’s work, I doubt my abilities and get discouraged.

When I see all the many wonderful images out there, I feel mine are inferior by comparison. When I see the great images from locations that I have photographed, I am disappointed that I did not see them. I am overwhelmed by the sheer number of great photographers out there and think: there’s no room left for me. I feel inadequate when I see so many original ideas…that I did not think of.

And so I get depressed at the thought of competing with all of these great images and photographers.

But therein lies my mistake: creating art is not a competition and I should not compare my work to others. I am not trying to be better than someone else, I am trying to better myself.

Everyone has the ability to be great at something, but I cannot be great at all things. I cannot be a a great portrait photographer, a great landscape photographer, a great street photographer, a great floral photographer and a great still life photographer. But there is something I can be great at, and I cannot achieve that greatness by focusing on what I’m not good at. I must recognize my talents and be appreciative for those.

I need to remember that art is not a competition. When I create from my vision there are no losers, only winners.

Cole

P.S. I used to think I was alone in having these feelings, but as I have shared these thoughts with others (including some big name photographers) I’ve learned that many feel the same way. We are all human and share the same frailties, foibles and insecurities. No matter who we are, it seems to be human nature to compare ourselves to others and to sometimes feel inadequate.

March 24, 2013

Ancient Stones No. 12

“Ancient Stones” is a portfolio that I started last year when I visited Joshua Tree for the first time in 20 years. This trip brought back many great memories because it was the site of one of my earliest dates with my wife Dyan. We camped amongst the boulders, sunned ourselves on the rocks and listened non-stop to U2’s “Joshua Tree” album. What wonderful times those were!

Ancient Stones No. 12 above is the latest image in the series and I love it! But why do I love it? Is it because it evokes wonderful memories or do I love it because it’s a good image? Evaluating your own work is very difficult, especially when it’s tied to to things like memories, praise and the opinions of others.

Recently I’ve been corresponding with several photographers on the topic of finding your own vision. I explain that one of the first steps I took was to divide my work into two piles; work that I REALLY loved and everything else. By isolating the work that I really loved, I would then try to understand what those images had in common and pursue that “vision.”

It sounds like a simple exercise, but it wasn’t for me. I actually had difficulty in separating what I thought about my work from what others thought. I noticed that if a lot of people liked one of my images, it started to affect how I felt about that image also. If one of my images won a competition, I took that as evidence that it must be a good image and that affected my opinion of it. I became so addicted to “positive feedback” that I began seeking it by producing work that I thought others would like, and in time I lost sight of what I loved.

Upon realizing this, I committed that I would never again produce images simply because others liked them and I adopted a new policy: Never Ask Others About Your Work.

To isolate myself from other’s opinions I stopped asking my friends if they liked my work. I stopped asking my mentor what what she thought of my images. I no longer approached the experts to ask their opinions and I no longer attended portfolio reviews for input. I purposely removed the clutter of other voices and focused only on what I thought.

So what happened? I once again began to understand what I loved and focused only on that, which turned out to be a key ingredient to finding my vision. I became more confident in my work and I was certainly more satisfied. Now the measure of my work and success was internal rather than external.

There was another important reason why I stopped asking others about my work; no one knows more about my vision than I do. Their advice, though generally good and well intentioned, was not coming from my point of view or vision. Increasingly I found that my vision and their advice was in conflict, and I realized that I had grown to the point where I was ready to decide for myself what my work needed.

Those of you who are familiar with my practice of “Photographic Celibacy” might recognize a reoccurring theme in my decision to “Never Ask Others About Your Work.” In both cases I am attempting to understand myself and my vision, and to pursue it without being influenced by others. In both cases I am isolating myself from the thoughts, opinions and images of others.

This idea of never asking others about your work, was echoed and reinforced by one of my favorite books, The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. The main character is Howard Roark, an architect who is an uncompromising individualist, who defines success by being true to self and creating work that he loves. His designs are unique and he rejects the traditional designs and opinions of the experts.

However his friend and fellow architect, Peter Keating, has an opposite view of success: he seeks the approval and admiration of others. In one of my favorite scenes, Peter asks Roark what he thinks of his latest design and this is Roark’s response:

“If you want my advice, Peter,” he said at last, “you’ve made a mistake already. By asking me, by asking anyone. Never ask people, not about your work. Don’t you know what you want? How can you stand it, not to know?”

There is strength and power in knowing what you want. Finding your vision and pursuing it is a wonderful feeling that gives conviction to your work. Like Photographic Celibacy, “Never Ask Others About Your Work” may seem to run contrary to common wisdom, but I have found it to be instrumental in helping me to know what I really love and keeping me focused on my vision.

Cole

May 19, 2012