Category: Philosophy

March 24, 2013

Ancient Stones No. 12

“Ancient Stones” is a portfolio that I started last year when I visited Joshua Tree for the first time in 20 years. This trip brought back many great memories because it was the site of one of my earliest dates with my wife Dyan. We camped amongst the boulders, sunned ourselves on the rocks and listened non-stop to U2’s “Joshua Tree” album. What wonderful times those were!

Ancient Stones No. 12 above is the latest image in the series and I love it! But why do I love it? Is it because it evokes wonderful memories or do I love it because it’s a good image? Evaluating your own work is very difficult, especially when it’s tied to to things like memories, praise and the opinions of others.

Recently I’ve been corresponding with several photographers on the topic of finding your own vision. I explain that one of the first steps I took was to divide my work into two piles; work that I REALLY loved and everything else. By isolating the work that I really loved, I would then try to understand what those images had in common and pursue that “vision.”

It sounds like a simple exercise, but it wasn’t for me. I actually had difficulty in separating what I thought about my work from what others thought. I noticed that if a lot of people liked one of my images, it started to affect how I felt about that image also. If one of my images won a competition, I took that as evidence that it must be a good image and that affected my opinion of it. I became so addicted to “positive feedback” that I began seeking it by producing work that I thought others would like, and in time I lost sight of what I loved.

Upon realizing this, I committed that I would never again produce images simply because others liked them and I adopted a new policy: Never Ask Others About Your Work.

To isolate myself from other’s opinions I stopped asking my friends if they liked my work. I stopped asking my mentor what what she thought of my images. I no longer approached the experts to ask their opinions and I no longer attended portfolio reviews for input. I purposely removed the clutter of other voices and focused only on what I thought.

So what happened? I once again began to understand what I loved and focused only on that, which turned out to be a key ingredient to finding my vision. I became more confident in my work and I was certainly more satisfied. Now the measure of my work and success was internal rather than external.

There was another important reason why I stopped asking others about my work; no one knows more about my vision than I do. Their advice, though generally good and well intentioned, was not coming from my point of view or vision. Increasingly I found that my vision and their advice was in conflict, and I realized that I had grown to the point where I was ready to decide for myself what my work needed.

Those of you who are familiar with my practice of “Photographic Celibacy” might recognize a reoccurring theme in my decision to “Never Ask Others About Your Work.” In both cases I am attempting to understand myself and my vision, and to pursue it without being influenced by others. In both cases I am isolating myself from the thoughts, opinions and images of others.

This idea of never asking others about your work, was echoed and reinforced by one of my favorite books, The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. The main character is Howard Roark, an architect who is an uncompromising individualist, who defines success by being true to self and creating work that he loves. His designs are unique and he rejects the traditional designs and opinions of the experts.

However his friend and fellow architect, Peter Keating, has an opposite view of success: he seeks the approval and admiration of others. In one of my favorite scenes, Peter asks Roark what he thinks of his latest design and this is Roark’s response:

“If you want my advice, Peter,” he said at last, “you’ve made a mistake already. By asking me, by asking anyone. Never ask people, not about your work. Don’t you know what you want? How can you stand it, not to know?”

There is strength and power in knowing what you want. Finding your vision and pursuing it is a wonderful feeling that gives conviction to your work. Like Photographic Celibacy, “Never Ask Others About Your Work” may seem to run contrary to common wisdom, but I have found it to be instrumental in helping me to know what I really love and keeping me focused on my vision.

Cole

March 15, 2013

If I were to ask you to list five great locations for creating great images, what would you list? Here’s my list that might be typical:

- Yosemite

- Iceland

- Big Sur

- Japan

- The African Plains

These beautiful locations would almost guarantee a great image! Think of the great work done here: Yosemite and the iconic images of Ansel Adams. When I think of Iceland will I forever see the incredible iceberg images of Camile Seaman in my head. Or how about the work of Edward Weston in the Big Sur area or Michael Kenna’s incredible minimalistic work from Japan. And Africa…could anything be more definitive than the work of Nick Brandt?

But do you know what would happen if I were to visit these locations, say Yosemite for example? I’d be looking for the spots where Ansel created those famous images so that I could recreate them for myself. And while I might be able to create a pretty nice image, it would neither be original or be as good as Ansel’s. Remember, Ansel has already done Ansel and I’m not going to do him better!

And so it begs the question; do I need to photograph at places such as Yosemite, Big Sur or Africa in order to create great images? Can’t great images also be found in ordinary places?

Yes they can. I believe that ordinary places have just as many image opportunities as the exotic places we all dream of visiting. So let me suggest another list of locations where you can create great images:

- Your neighbor’s yard

- Your bedroom

- A greenhouse

- A hotel

- In your car

They don’t sound very exciting when compared to that first list, so let’s take a look at why I’ve chosen these ordinary and even mundane locations. First, they are very accessible: no passport needed, no time off from work and no travel expenses.

But there’s another more important advantage: Ansel and Seaman and Weston and Kenna and Brandt have not photographed there and so you don’t have their images floating around in your head. You are free to see these locations in a fresh and unique way, and you are free to be the first to create great images there!

Here are some examples of my images from those very “ordinary” locations:

My neighbor’s yard.

My bedroom.

A greenhouse.

A hotel.

In my car.

~

Great images do not need great locations…or perhaps better said; great images can come from everyday and ordinary great locations!

Yes, I have traveled to many exciting locations around the world and and I’ve created images there that I’m proud of, but I’m just as proud of my images from these “ordinary” locations.

Here are a few more examples of images from ordinary locations:

At my feet.

A friend.

Something my daughter made.

At a flea market.

Before my son’s senior prom.

The river in my town.

On the way to work.

My backyard.

At a local tree nursery.

On the side of the road.

At a family get together.

Along the railroad tracks.

At my kitchen table.

In my home office.

Along the river in my hometown.

~

The “key” to a great image is not location, but your Vision and your ability to see differently than those who have gone before you.

It’s a hard thing to do, but it is the key.

Cole

March 7, 2013

What do The Beatles, Las Vegas, Death Valley and three new images all have in common?

I often cite The Beatles as being one of my photographic inspirations. Not because I grew up with them and love their music, but because I admired how they never “froze in time” in a futile attempt to remain popular by staying the same. Rather, they flaunted conventional wisdom and would change styles at the height of their popularity. As I listen to their music I am in turn inspired to grow, change and to stay fresh by trying new things.

So what has that to do with this story? Well for Christmas my wife surprised me and purchased tickets to The Beatles LOVE by Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas. The seats could not have been better, the production was unbelievable and the music was…well…it was the Beatles!

We then decided to stay a few extra days in Las Vegas to celebrate our wedding anniversary and Valentine’s Day. The question was what to do with our extra time? We decided to head off to Death Valley so I could show her some of my haunts and so she, a runner, could run at 285 feet below sea level see what it felt like to be Superman!

While she was out running I was very anxious to have another go at Death Valley, but this time capturing my images as RAW files rather than puny JPEG’s! (see my last several posts for the full story). While there I did create three new images.

Time No. 4

Dunes of Nude No. 85

Discordant Lines No. 2

The Beatles, Las Vegas, Death Valley and three new images, how can life get any better than this?

Cole

March 1, 2013

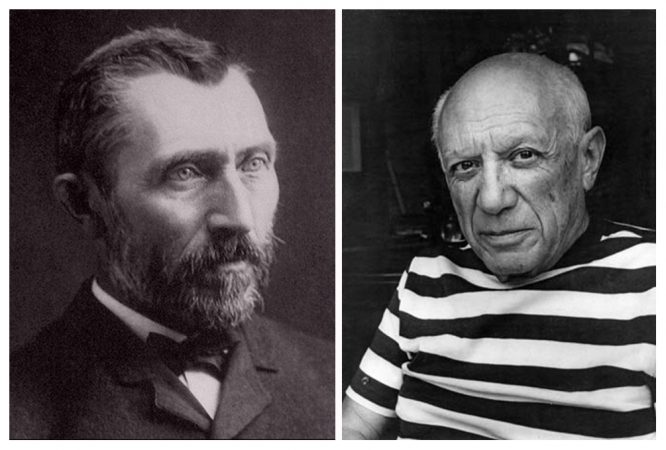

An imaginary discussion between Vincent Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso

Pablo: Vinnie, how have you been? Wonderful new piece, what do you call it?

Vincent: I’m not sure, maybe “Big Moon in Sky” or something like that. My friend Don suggests I call it “Starry Night.” He wants to write a song about it!

Pablo: Question for you, what paint did you use on this? Is this the 3000 series of paints?

Vincent: No! It’s the new 5000, I wouldn’t be caught dead using the 3000, have you seen the tonal range on those paints? Appalling!

Pablo: I agree, personally I wouldn’t ever purchase a painting if it used those paints.

Vincent: Agreed, what are those other painters thinking?

Pablo: This canvas is nice, what is it?

Vincent: It’s a new canvas, out of Germany and I like the texture on it but it’s still not exactly what I’m looking for. I’ve been searching and searching for the right canvas and I’m just not happy with anything yet.

Pablo: I know what you mean, I’ve been searching for years for the perfect canvas and will not rest until I do. Hey, I’ve been noticing the perspective on this piece and it leads me to believe that you’re using a 54″ easel? Placing your canvas a little higher are you?

Vincent: Yes but not a 54, it’s a 57 and combined with those new Hartford stools (they have a great padded cushion) I sit so much higher and really like the feeling when I’m working. Plus, they adjust so easily.

Pablo: Wow, I’ll have to check those out, I think Al’s apothecary is carrying them.

Vincent: I heard a rumor that you’re trying some of those new camel hair brushes? Tell me it isn’t so Pablo!

Pablo: Where did you hear that? It’s true, but I’m not telling anyone. They are so much better than the cat hair brushes that I normally use. Have you tried them?

Vincent: I wouldn’t be caught dead with one of those, do you know what would happen people found out that I was using Camel hair! I don’t have to tell the scandal…

Pablo: I see you’re using those new frames from Friar Wilson, how do you like them?

Vincent: Pretty good, they’re a lot cheaper so my margins go way up. I need a little extra “ching” so that I can purchase that new satchel from Mary the Seamstress. Have you seen it, it matches my frock and is really nice for carrying around my art supplies.

Pablo: Yes, those are nice, but not as nice as those wild colored ones made by the Maid Vivian!

Vincent: You’re nuts, those look horrible! You’ve got a poor sense of color Pablo.

Pablo: Me??? You’re the one stuck in the past man, wake up!

Vincent: Look at us, talking about paints, easels and brushes. Does any of this really matter? I mean, do you think photographers sit around and talk like this? I suspect not.

Pablo: Good point. Maybe there’s more to painting than equipment and tools?

Vincent: Perhaps it ought to be more about the art?

February 23, 2013

http://nlwirth.com/blog/cole-thompson-interview

Typically, I begin with an obvious question about what initially inspired you to pursue photography. I’ll ask about that later, but I’d like to begin with asking you about your overall understanding of vision and why you think it is so important.

Cole: Why is vision so important? Because it’s what makes our work unique. It’s the one ingredient that can transform a “captured photograph” into a “created image.” It’s more important than technique or an exotic location; it’s more important than a great camera or an expensive lens. With vision, you can take the simplest scene and create a masterpiece. Without vision, you can have all of the best equipment and techniques, and all you’ll end up with is a technically perfect “photograph.”

My rule of thirds states that a great image is comprised of 1/3 vision, 1/3 the shot and 1/3 processing. However, vision is the most important of these because that is what should drive both the shot and the processing. Vision transforms what we see with our physical eyes into what we see with our mind’s eye.

Sometimes we focus on the other things– equipment, technique and gadgets– because developing one’s vision is hard. Understanding and achieving vision is a nebulous concept, and it doesn’t come very easy for many of us. I used to think that I could compensate for my lack of creative ability by becoming extremely good at the technical. I studied the works of other photographers and mimicked them– specificallyAdams and Weston– in an attempt to be as good as they were. However, in the end, all I became was a great imitator. I had focused on everything except that which would make my work unique! Vision.

Nathan: What, then, is your overall vision for your work? Is it a single thing– or, perhaps, many, ever changing things?

Cole: I hope semantics and words do not get in the way of my trying to explain vision. But, for me, vision is not a thing but an understanding. My vision was always there; I didn’t create it, and I didn’t develop it. I simply discovered it and have learned to use it. But to fully use it, I must put out of my mind all stumbling blocks such as pride, envy, competition, insecurity and seeking recognition. These are barriers to vision and they impede the creative process.

I know that some could argue that there is nothing wrong with wanting recognition, or that competition is good, or that envy can motivate you to do better. I understand those arguments and for many things in life that might be true, but I don’t believe it’s true for the creative process. Anything that shifts your focus away from your vision and creative process is a distraction. If you are shooting to become famous, to win competitions or to get praise … you will not do your best work. It is only by learning to ignore those distractions and focusing completely on your creation that you can excel.

But let me also be clear that once you’ve created honest work through vision and produced something that you love, then there is nothing wrong with exhibiting, winning competitions, receiving recognition and praise for your work. Those things are the natural outcomes from following your vision, but if you only create for those goals then your work will lack conviction and power. That is my honest opinion.

I sometimes do talk about “developing” vision, but the more I live with my vision and think about it, the more I believe we actually don’t develop it. I believe we just come to understand it better and learn to follow it more. As we have new experiences in life, our vision naturally changes and so does our work. I just had someone express the thought that vision sounded limiting, and that once you find your vision your work will forever look the same. I disagree with that; our vision has nothing to do with the subjects we photograph, our style, or the techniques we use. Discovering one’s vision does not mean one’s work is doomed to be forever the same. In fact, I think that the opposite is true, that as we continue to understand our vision better and clear our minds of those distractions, our work will be ever changing. This has been my experience.

Nathan: I find your response very intriguing because it addresses, in a sense, the mystery of where creativity even comes from. It sounds like you advocate getting out of the way of such questions– and the whole concern of how to find it or cultivate it– and just doing it, just creating the work, the rest inevitably falling into place. I think many would wonder, however, if this can really only be done after you have managed to harness the basic understandings necessary for working with the mechanisms, the workings of the camera. In retrospect, do you think you arrived at your conclusions about what vision means as a result of much trial and error– and, perhaps, even pursuing recognition and acceptance and praise too early (only to find that it did not really justify and/or satisfy what you were really interested in ultimately doing with your work because it was, as you suggest above, blocking your creative impulses)?

Cole: I think you’re right. I don’t care as much about the “why” behind things. I just want to create. Talking about it and analyzing it is not my style, and, besides, I’m not certain that knowing those answers will make me a better artist. In my opinion, doing trumps analyzing.

There is no doubt that a certain technical proficiency is needed to be a photographic artist. Without those skills, we would be unable to transform our vision into an image. We could see the image in our own minds, but we would never translate it into something that others could see.

However, I think that the pendulum has swung too far and for too long in emphasizing the role of technical skills in photography. Yes … theyare important, even critically important, but couldn’t the same be said for vision? Is one really more important than the other and do the technical skills truly need to come first? I frequently hear people say that that you cannot really excel in the creative until you have developed a certain technical proficiency, but I believe that kind of thinking is backwards. As I look back on my photographic life, I now see that my emphasis on the technical was a substitute for working on the creative and that focus actually retarded my creative growth. If I could do it all over again, I’d focus on the creative right from the start and learn the technical only as my images required it.

The technical, in my opinion, is far easier to learn than the creative. I believe that’s one of the reasons we photographers focus so much on equipment and technical processes; we do it because we know how to do that. I think we are a bit uncertain how to find our vision, so we take refuge in what we can grasp: the technical. That’s what I did. Because I doubted my creative abilities, I compensated by becoming an expert technician. And that did carry me for a while, but, in the end, I was just another photographer creating technically perfect images that lacked soul. Neglected, my creative side atrophied and that further reinforced my belief that I had no creative abilities.

So bottom line, I’d encourage people to focus much more on the creative and much less on the technical. And I’d pursue the technical only in response to a creative need.

Nathan: I think one of the most talked about and, perhaps, most misunderstood question on the minds of many artists, including, of course, photographers, is: what exactly is fine art? Typically, many seem to respond that the answer is inextricably bound to the taste of the viewer, the goals of the creator, and inevitably, the opinion of the critic and the curator. Is fine art even something concrete, palatable– or even real– or is it more of a marketing tool or, perhaps, even a way for critics, sellers, and artists to label the work? I am curious about what your response to these questions might be– especially taking into consideration your understanding of vision.

Cole: I am not interested in defining “fine art,” and I don’t care how anyone else defines it either. What some expert, art critic, gallery owner, or curator calls fine art has no impact on me or what I do. They are merely one of a million opinions floating around in the ionosphere. When I look at an image, I simply know if I like it or if I don’t. Does anything else matter? Do I like an image less because someone tells me that it’s not fine art? (I’ve had that happen before).

For me, creating is doing what I want and not caring what others think. It is pursuing my own vision regardless of what others think. It’s about being so absorbed in the creative process that I’m not even aware of what others think! That moment when you realize that it’s irrelevant what others think is a wonderfully liberating feeling.

At the end of the day there is only you, your creations, and your opinion of your work. In the end, nothing else matters.

So why do some feel the need to define fine art? I’m sure one reason is simply to be able to classify work into categories so that we can communicate; for example, when I say that I create “fine art photography,” we all generally know what I’m talking about. So to some degree, we use these terms simply to be able to communicate, but I don’t spend much time worrying about a precise or universally accepted definition. I don’t have the time nor the patience.

Just so someone doesn’t think me a hypocrite, I do use the term “fine art” in my marketing. For example, I have targeted the Google search phrase “B&W Fine Art Photography” (search me, I’m number 1 out of 2,650,000 search results). So even though I have no use for defining “fine art,” I do recognize that it has a generally accepted meaning and that people use it to search for a certain type of image. I do use that to my advantage.

Nathan: Looking through your various projects, I see quite a few directions that you have followed— from “The Lone Man” series to the “Monoliths” series to “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” series and others— do you think there is any particular thread or overall theme that ties these together or are you moving from series to series individually?

Cole: There is no intentional connection between my portfolios and there is very little connection in terms of subject matter, but my work is all tied together by my vision, and that sometimes can produce a similar look between bodies of work– even though it is not intentional.

Many times over the years, people have advised me to pick one subject, focus on that and become known for that. However, that advice never sat right with me and I’ve always ignored it. I’ve been very fortunate to photograph a wide variety of subjects, and I’ve loved each project that I work on. I’d be bored if I was restricted to landscapes or any other individual subject! I believe that great work comes from passion, and pigeonholing yourself is not likely to produce much, if any, passion.

My roots are in traditional landscape photography, so you will see that influence in my portfolios. For example, my Death Valley portfolio, which appeared in the Sept/Oct 2012 issue ofLensWork, hearkens back to my roots much more than my other recent work. Then take a look at my “Ceiling Lamps” series and you’ll see a completely different subject and approach. Move onto my “Monoliths” portfolio and I’ve again changed subject, look, and style. Then there is my architectural series, “The Fountainhead,” and, well, you get the idea. My variety seems to fly in the face of the conventional wisdom to pick one subject and become known for that, but I don’t agree with that conventional wisdom.

People write to me all the time, almost sorrowful because their work is so varied. They seem to feel that this indicates a lack of concentration or discipline, which I don’t think is necessarily so. Following your vision doesn’t mean that your work focuses on the same subject or is similar looking. Vision should never be confused with a “look” or “style,” but, rather, it should be understood as an approach to creating images. While my portfolios have no common subject or theme, I do believe there is a common thread connecting them, and that thread is the way Isee and treat those subjects. I reject the concept that you must focus on one thing or develop a “look” to become successful; I would, instead, propose that the key to success is finding and following your vision.

Sometimes my work is not a “critical” success, but that is not how I measure success. I measure it by how I feel about the project and not by how others react to it. Take my portfolio “Ukrainians, With Eyes Shut,” a series of street portraits in which I asked the subjects to shut their eyes: this portfolio generated very little critical interest, but I love it, nonetheless. And, conversely, my series “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” was extremely well received, but that does not make me feel any differently about this body of work or make me go out and duplicate it (which people have advised me to do). There is this great quote that I’ve modified to sum up how I feel: what anyone else thinks about your work is none of your business.

I think my work is so varied because I don’t study other people’s work, so I’m very unaware what others are doing. This means I’m less likely to say “Why bother photographing Auschwitz? It’s been done to death and I could never do better than so-and-so, so why try?” This kind of ignorance is bliss because it allows me to photograph something without being intimidated or influenced by others work.

Nathan: I have to talk to you about your photography celibacy, your decision to avoid looking at what others do with their photography so that you are not indirectly influenced by it or discouraged from pursuing a theme or subject matter that interests you because someone else has done it. How far do you take this? I know, from previous interviews that you have given that you have great admiration for Michael Kenna and Alexy Titarenko (two of my most favorite photographers). Do you still check in from time to time to enjoy their latest work? I’ll have to confess and say that while I most certainly understand your reasoning behind this, I personally could not sacrifice the pleasure of witnessing the ongoing “conversation” and “evolution” that has been happening since the beginning of photography. In other words, for me, a significant part of my enjoyment of photography is the work of others. I can easily guess that your photography celibacy is often met with a challenge from other photographers. I’d love to hear more about your thoughts on this.

Cole: I learned photography by reading and by studying the work of the great masters. As a boy, I spent hours a day looking at images, analyzing them, and trying to decide what I loved about them and why. It was such a huge part of my life that it might seem that photographic celibacy would be a difficult thing for me to undertake.

So why take the “vow of celibacy?” Well, because at some point, I transitioned from photographer to artist and my desire to uniquely create became the most important thing in my life, even more important than enjoying great photography. It’s really not a sacrifice for me because I’m so focused on my creative process that I don’t miss it.

Do I peek at Kenna’s or Titarenko’s work from time to time? No. The only work I look at now is the occasional friend’s images.

Why do I continue this practice after almost five years? Let me illustrate: not long ago I saw an image of three telephone poles entitled “Three Crosses” by Brian Kosoff. The image just floored me and I purchased it. But something else occurred; I immediately found myself thinking “where can I find telephone poles like that?” I had to consciously stop myself and remind myself of my goal! Perhaps it’s just me, but when I see a great image my mind immediately starts thinking about how I can imitate the shot or recreate the look. So now I just avoid that altogether.

There are many like you, who understand why I do this but you choose a different path, and I respect that. And there are a few who argue adamantly against my practice because they generally feel that art builds upon that which has come before, and so to progress you must be aware of what has come before.

Another variation of that argument is that you must study great art to be able to create great art. However, I just don’t buy the argument. How can filling your mind with other’s images help you to be more creative or unique? It has the exact opposite effect on me! Original thinking is hard to do, and while I have not completely achieved that yet, I’m determined to try.

I think the best defense I’ve heard for Photographic Celibacy is that it’s a useful tool at a certain point in a person’s creative development. And once that tool has served its purpose, you move on and find another. Certainly I don’t argue that I’ll be celibate for the rest of my life, but for now I find the practice useful in helping me to see more uniquely so that I can further develop my vision.

There is something else that I have found equally important in developing my vision, and that’s learning to not care what others think of my work. To create for oneself and not for the praise of others can bring great power and conviction to your work. I’m not saying that I don’t enjoy exhibiting and being published. I really do, but that’s no longer the reason why I create. That’s now an extra benefit of creating.

Edward Weston has always been a role model for me in this area. Here is my favorite Weston story as told by Ansel Adams:

“After dinner, Albert (Bender) asked Edward to show his prints. They were the first work of such serious quality I had ever seen, but surprisingly I did not immediately understand or even like them; I thought them hard and mannered. Edward never gave the impression that he expected anyone to like his work. His prints were what they were. He gave no explanations; in creating them his obligation to the viewer was completed.”

It is very hard to put out of your mind what others will think of your work, but it really is quite liberating. Ironically I’ve also found that, in pleasing myself, my work has become more pleasing to others.

Nathan: Do you think it is necessary for an artist to always remain fresh, unique, and on the cutting edge (whatever that actually even means)? For example, some might say that choosing to paint in a similar style to (or be influenced by) the great Dutch Masters– or the wonderful Hudson River School painters of sublime landscapes– would not be following the mandate that art must always progress, always change, always seek to say something new. I strongly feel that, by definition of the very act of the individual creating something in his or her own voice, that someone who does work in a style of the past– or any similar subject matter already covered by others– is still creating something unique and fresh because, by definition, it cannot be the same as the work that inspired it (the work being inextricably bound to the vision of its creator).

Cole: I’ll be honest Nathan: I’ve never studied art, so I cannot speak intelligently or with any perspective other than my own. I work hard to not think of my work in relation to what others are doing. I do not compare it in order to judge whether it is new, fresh, or unique. I do not care if it is cutting edge in someone else’s opinion; that type of thinking is not productive and would drive me crazy. I am completely serious when I tell you that I could care less if the most renowned art critic declared my work good or bad; it makes no difference to me.

But I do care if my work is new compared to what I have been doing, and I do care if it’s unique compared to my past work, and I do care if I think the image is good. This is all that matters to me.

Now it’s very hard to be objective about one’s own work and to answer the question “is it good?” I generally find that I love 100% of my images when I view them in the field, and about 50% of them when I look at them on the computer, about 10% of them when I do my first-pass processing, and about 1% of them when I look at them a couple of days later and finally about .25% of them when I view them a few weeks later. I do find that time helps give me a more objective and realistic perspective of my work.

Nathan: So let’s shift gears a bit and focus on some of your particular series/portfolios. I’d love to hear a little more about the vision or, if applicable, thinking behind some of your series. Specifically, “The Lone Man,” “Monoliths,” “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau,” “Dunes of Nude,” “Harbinger,” and “Ceiling Lamps.”

Cole: Each of my portfolios have come about spontaneously, suddenly, and without planning. When I see something, it excites me and I pursue it. How could life be any simpler or better than that? For a long time, I’ve kept a list of ideas, projects that I hope to pursue, but the truth is that I’ve never started a single one of them! I still keep the list, and I still think they’re good ideas, but I’ve never gotten excited enough to start one of them.

I typically complete my portfolios very quickly; many have been completed in days and weeks while some others have dragged on for a couple of years. This brings to mind a misconception that I had most of my life and one that I think others have: that a “serious” project will take years to complete. I always thought that the longer a project took, the better it must be. However, I no longer believe that. I don’t think there’s necessarily a correlation between how long a project takes and how good it is. For example, “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau”portfolio was completed in less than two hours.

So how long, then, should a project take? It takes as long as it takes.

The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau: I was visiting my son, who was serving in the Peace Corps in Ukraine, and because I’m part Polish we decided to see Krakow. As we planned our activities, the family decided that they wanted to visit the concentration camps. I didn’t want to visit there because sad places make me sad, and while my wife loves a good cry, I tend to avoid discomfort! However the majority ruled and so off we went.

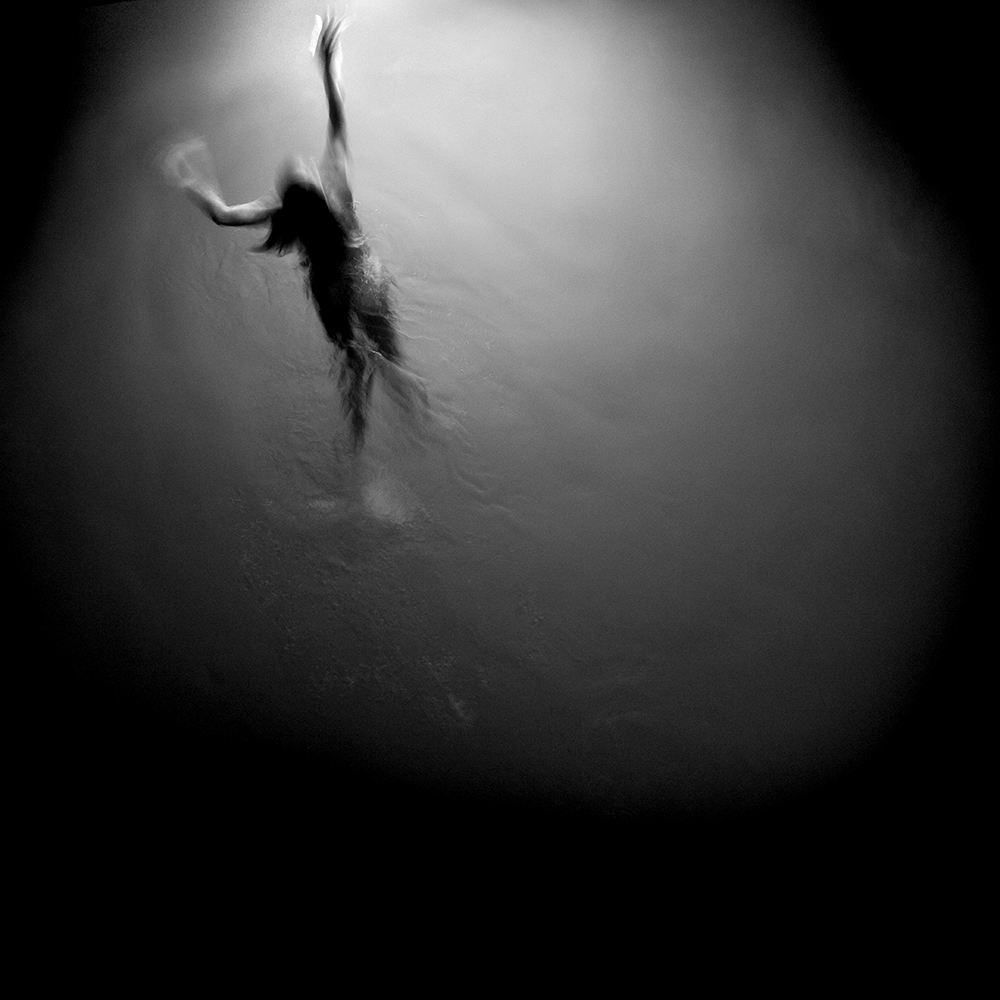

I had my equipment with me but decided not to photograph because I thought it might be sacrilegious. The tour started inside a building where we saw the documentation that was kept on each prisoner. We saw the infamous piles of shoes, glasses, hair and etc. We were about ten minutes into the tour when I started feeling claustrophobic and found it difficult to breathe. I signaled to the family that I was going outside to seek relief, and once outside I did feel a bit better. However, as I began to slowly walk, I looked down at my feet and began to wonder who had walked in these same footsteps before me, and what had been their fate? With each step I could not shake that question: who had walked here before me and now were dead? Then I wondered, perhaps metaphorically, if their spirits still walked here. And then the idea hit me; I must photograph the spirits of the dead who still walked the camps.

I had been working with long exposures for some time, so I was technically prepared. I had even used long exposures to create two recent images with people in them; “The Angel Gabriel” and “Two Kimonos,” so I understood a bit about creating ghosts. Armed with a little experience, an idea, and some inspiration, I started to work. I would use long exposures to photograph the other visitors at the camps and to turn them into ghosts. These unsuspecting tourists would stand in proxy for the spirits who had died there. Our tour bus was to leave in less than one hour and so I had to work quickly. I literally ran from shot to shot to complete these images.

One of the largest challenges was surreptitiously photographing the other tourists. When they saw my camera and tripod pointed at a scene, they politely held back and didn’t enter the area, which, ironically, was exactly what I wanted! Fortunately, I had encountered this challenge before when I was photographing in Tokyo, so I had developed some simple techniques to trick people. I’d turn my back, act like I was on the phone and when they wandered back in I would use a remote shutter release to take the picture.

To create the ghosts, I used 10 to 30 second exposures, and I had to take about ten shots to get a single one that worked, which consumed precious minutes as I raced against the clock and the departing bus. In the end, the bus tried to leave, but my family protested and my wife dragged me back to the bus. In that short time at Auschwitz, I was able to create twelve images and then another three at Birkenau, our next stop. These were the fifteen most important images in my photographic life thus far, and if I never create any better than this, I’ll be happy with this accomplishment. Often the shot was ruined if someone stopped moving during my long exposure because this person would then be recorded as a mortal instead of a ghost. In only one of my images do I purposely leave a “mortal” in the scene, and it’s been interesting to watch people interpret what that means. I have my own interpretation, but I enjoy hearing what others think– and I’ve heard a number of very interesting interpretations.

View the complete “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” series here.

The Lone Man: I was shooting long exposures at one of my favorite dive spots inLaguna Beach when a group of tide poolers walked into my scene. While I was waiting for them to leave, I decided to take a test shot so that I would have my exposure all set when they left. I recorded a 30 second exposure and when I looked at the image, I was surprised to see that one man had been perfectly recorded because he had stood perfectly still for the 30 seconds. As I looked at him, I noticed something very familiar about his stance; I had seen this attitude before. I realized that what I was seeing was the look that comes over people as they stand on the “edge of the world” and look out into the infinite expanse of ocean. They become still, contemplative, pensive, and thoughtful. And now that I had consciously noticed this, I began to see it in people everywhere which inspired me to create “The Lone Man” series. Here is my artist statement for the project:

Something unusual happens when a person stands on the edge of the world and stares outward. They become very still and you can almost see their thoughts as they ponder things much greater than self:

Where did I come from?

What is my purpose?

What does it all mean?

What is beyond the beyond?

Do I make a difference?

Is there more?

At that moment they are The Lone Man, alone with their questions and thoughts about life, the universe and beyond. People are affected by this time of meditation and often vow to make changes in their lives. But this moment is short lived as these weighty thoughts are replaced with more immediate concerns:

Should I eat at McDonalds or Burger King and should I try that new green milkshake?

View the complete “The Lone Man” series here.

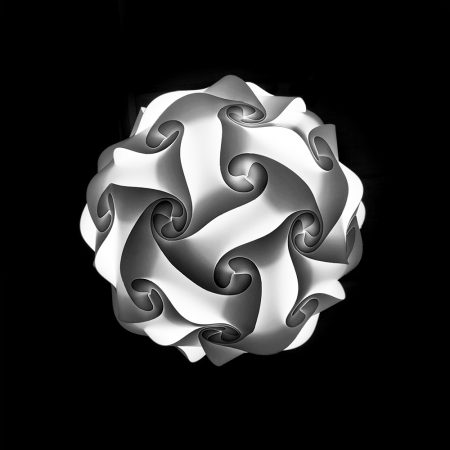

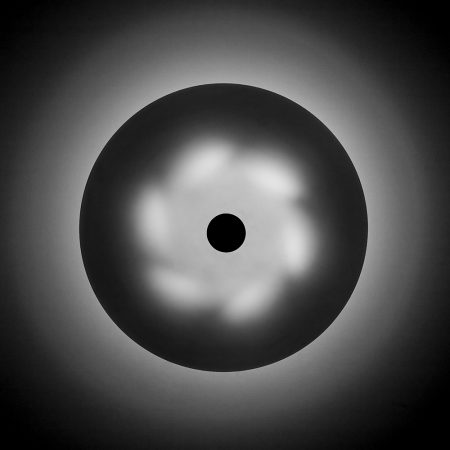

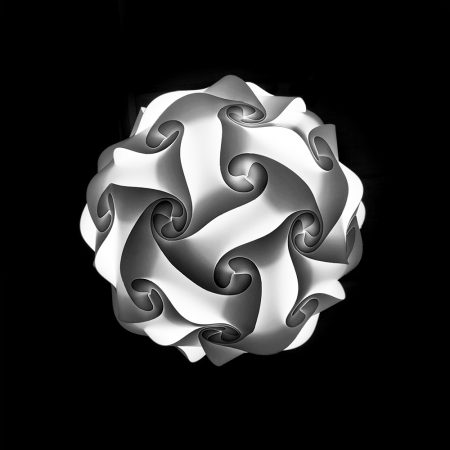

Ceiling Lamps: I was standing in a hotel lobby in Akron, Ohio, waiting to check out, when I happened to look up. What I saw was a ceiling lamp that looked fantastic when viewed from directly below. It really didn’t look like a ceiling lamp to me at all!

I pushed all the lobby furniture out of the way and lay on my back to get a better perspective (which triggered offers of CPR, mouth-to-mouth, and calls to 911). This is the first ceiling lamp I created and from there it was all great fun to seek out these lamps and photograph them– all from the same perspective and style.

This was a fun, whimsical project, and I had a great time creating it. Once you become attuned to something, you begin to see it everywhere, and that’s what happened to me with this project. Someone once told me that I’d probably never win any critical acclaim for this project, and that’s okay. That’s not why I created it.

View the complete “Ceiling Lamps” series here.

Harbinger: “Harbinger” was a single spontaneous image that I never thought would lead to a portfolio. I was photographing some mud hills in Utah,where it was over 100 degrees and my teenage son was doing the “are you almost done?” routine (if you have children, you understand). A parent can only take so much of that, so I finished up, and, as we were heading back to the car, I saw this solitary cloud moving rapidly across the sky. In an instant, I could tell by its trajectory that this cloud was going to pass over those beautifully symmetrical mud hills that I had been photographing and I wanted that image! I ran back up the hill, set up my camera and tripod in mere seconds … and got off this one shot.

I named it “Harbinger” because it seemed to me that this one little cloud was a harbinger of things to come. I absolutely loved the image but instantly wrote it off as a “one hit wonder,” not because I didn’t think it was a good image, but because I thought the chances of finding another similar cloud and interesting scene were about zero. Surprisingly, I have found a few more, and I continue to work on this project as the opportunity arises. Now this is a project that will take me years and perhaps my lifetime to complete!

Recently, I added a new Harbinger image that has more than one cloud, but I feel it still fits the description of a Harbinger [note: it is the middle image below].

View the complete “Harbinger” series here.

View the complete “Harbinger” series here.

Monoliths: When I first saw the Monoliths on the Bandon, Oregon beaches, I knew that I would photograph them. I have always been fascinated with what I call “Monoliths.” First, as a boy I read “Aku Aku” by Thor Heyerdahl and learned about the giant stone statues of Easter Island, and, later, I saw 2001 A Space Odyssey and was fascinated by the monolith discovered on the moon. I don’t know why Monoliths fascinated me so much, but I have always thought of them as conscious beings who have always existed. I imagined them standing there motionless for eons, observing man as he scurried about full of self importance. That always made me smile.

Each September I return to Bandon to photograph, it’s my favorite stretch along the Oregon Coast. And each year I question whether I should return because it seems as though I’ve photographed the Monoliths in every conceivable light, from every angle and in every type of weather. But I do return and I do always find new images.

View the complete “Monoliths” series here.

Dunes of Nude: During my trips to Bandon, I always drive down the coast to this great wind surfing spot. It has this very narrow strip of sand dunes that are compressed against the highway, and because of the very small space, it creates this miniature sand dune system. It looks just like a regular dune system except that it’s in 1/4 scale with everything miniature and compacted. This spot has always attracted me, but I never really came away with images that I liked.

However, on my last trip there, as the sun set, something really spectacular occurred. The low sun transformed the dunes into something completely different and during every minute of that last low sun, the shadows and shapes of the dunes changed. You have to work furiously because the sun is so fleeting. I became enthralled with this last 20 minutes of sunlight and this work has developed into a new project entitled “The Dunes of Nude.”

Initially I portrayed the dunes with very light tones, an unusual choice for me, but one that I thought I’d try. But after living with the images for a while, I reworked them all to be dark and “contrasty.” Sand dunes have been photographed by thousands of people and in a thousand different ways, and so part of me says that I’m unlikely to portray them uniquely. But another part of me considers that a challenge and that makes it all great fun.

The Dunes of Nude is a work in progress.

View the complete “Dunes of Nudes” series here.

Nathan: I’d like to shift gears again. One of the many parts of your talk in Palo Alto that I enjoyed the most, was your various pieces of advice, your useful chunks of wisdom, to photographers. I especially loved your advice to photographers to keep it simple, both with the purchase of the latest and greatest equipment and with processing images. I’d love to hear more about your thoughts on these matters.

Cole: I am a recovering technophile. I’ve always loved gadgets and always needed to have the latest equipment before anyone else did. My home was gadget central, and I thought that being able to own all of this equipment somehow qualified me. However, all of this equipment and these programs required a lot of time to learn and to maintain, so much so that I had less time for actual photography. It also led to the twisted belief that a great image was dependent upon my equipment. When I saw a photograph that I admired, I would ask the photographer about the camera, the lens and settings. What was I thinking? That if I knew their settings I could create the image myself?

This attitude continued until I started discovering my vision, and, as a part of that journey, I made the commitment to stop focusing on the things that didn’t matter and to focus, instead, on the things that do. I started focusing on my vision, composition and the image. I reduced my equipment and processes to the minimum “needed” to do the job. The first benefit of this new thinking was simply that I had a simpler workflow with fewer things to go wrong.

Then something else started to happen, this philosophy of simplification started affecting my work. I noticed that I was focusing more on simple images, simple shapes, and simple concepts. Over time, I found my vision, and my work became simpler in its construction and it improved.

I am not against technology or equipment or processes; in fact, I’ll adopt any tool or process that is needed to fulfill my vision. But all of those “things” are merely tools that are servants to my vision. They are not the masters.

Nathan: What equipment (camera, lenses, and filters) and software do you use?

Cole: I use the following:

- Canon full frame cameras with a 16-35, 24-105 and 100-400 lens.

- Tripod and remote shutter release.

- A polarizer, a Singh-Ray Vari-ND filter and an assortment of fixed ND filters.

- A HoodLoupe by HoodMan

- Photoshop and typically six tools [note: see Cole’s answer to the question below for what those six tools are].

- Wacom Tablet

- Epson 7900 printer using the supplied Advanced Black and White mode

Nathan: I’d love to hear about your basic (or not so basic) approach to processing. Do you know, when in the field, how you are going to later process an image or is this discovered during the actual processing (or, perhaps, a little of both)?

Cole: My belief is that the image begins with your vision. Most of the time I know exactly how I want the final image to look and I can “see it” in my mind’s eye. I’ve become comfortable enough with my Photoshop capabilities to know that if I visualize it, I can usually make it happen. And if I don’t have the skills to make it happen, then I’ll research and learn until I have found a way to translate that vision into my image.

You do not need a lot of Photoshop knowledge to be able to create with vision; in fact, I know very little about Photoshop, but I know enough. I typically use only six tools inPhotoshop because I’ve found that I don’t need more than that. I believe that many of the “extras” that people use just add another layer of cost and complexity to the process with very little improvement in the image.

Here’s an overview of the six tools that I use:

- RAW Converter – I use Photoshop’s RAW converter to set my image to a 16 bit, 360 ppi, 10X15 TIFF file.

- B&W Conversion tool – I like Photoshop’s b&w conversion tool and play with each color channel to see how it affects the different parts of my image.

- Levels – One of the most basic secrets to a great b&w image is to have a good black and white. I use Levels to set the initial black and white point and I use the histogram to judge this, never my eyes. Throughout my processing I keep my eye on that histogram to maintain a true black and white. Something else I do while in Levels is to adjust the midtones, which can radically change the look of my image and tends to set the direction I will take it.

- Dodging and Burning – This is where I do most of my processing and where I have the most fun! I feel most at home with dodging and burning because that’s how I did things in the darkroom. However the primary difference today is that I can take my time and exercise minute control over every part of the image. I use a Wacom tablet to dodge and burn because you CANNOT do a good job with a mouse.

- Contrast Adjustment – After I have the image looking great on screen, experience teaches me that it will print flat, and so I add some contrast. A monitor uses transmitted light and a print uses reflective light, so that means it will take a lot more work to get your print to look as snappy as it does on the monitor. Contrast helps.

- Clone Tool – I use the clone tool to spot my images. Cloning is so much better than in the old days when you had to spot every single print and your mouth tasted like Spottone all day!

I also like to mention what I don’t use: I do not use any plug-ins or b&w conversion programs. I do not use a monitor calibrator. I do not use curves or layers. I do not use special RIP’s or printer drivers. I do not use special inks and I am not on a lifelong search for “the perfect paper” (life is too short). I find that most of these “extras” only add a very small amount to the image, and that generally when an image misses the mark, none of those things would have made a difference anyway.

What would benefit most people’s work is to focus on vision, work on their composition skills and then hone the technical skills that are needed.

Nathan: I also love your advice about how one should not take advice and criticism from other photographers about how you should have or should not have made a particular choice when composing or processing an image.

Cole: People who give advice are generally well intentioned and oft times experienced. However their advice comes from their vision and their point of view, not yours which makes all the difference in the world. If I were to tell you how to process your images and you listened to my advice, then your images would begin to look like mine. That’s not right, they should look like your images that were created with your vision. Consequently I try very hard to not give advice to others about their images, how they should process them or how they should look.

Nor should you listen to the critics; art critics, professionals or others on photo sharing websites. Listen only to yourself and ignore the world. I remember the first image that I had created with my own vision, The Angel Gabriel. I showed it to my mentor at the time and she immediately said “Never center the image!” Something about her advice felt wrong, I had purposely centered it because that is how I had envisioned the image and how it felt. But, she was the expert and so I tried cropping it off center.

Seeing this image almost made me sick, this is not how I saw it through my Vision. This taught me to always follow my Vision, and to not to follow others advice (no matter how well-intentioned).

There is a saying that I try to live by: what others think of your images is none of your business. This requires a confidence in your vision and in your work, and when you have that confidence you’ll not need other’s advice.

One of my favorite books is The Fountainhead which is the story of Howard Roarke, an architect full of vision and self confidence. His friend Peter is a fellow architect who is insecure about his work and is constantly asking others what they think of it. At one point Peter comes to the Howard to ask his opinion about a building he has designed, here is Howard’s response:

“If you want my advice, Peter,” he said at last, “ you’ve made a mistake already. By asking me, by asking anyone. Never ask people, not about your work. Don’t you know what you want? How can you stand it, not to know?”

Now this vision and confidence does not come overnight, but it is my goal and I am constantly striving to reach that level of independence.

Nathan: Do you have any general advice for aspiring photographers?

Cole: My advice will be pretty predictable:

- Don’t listen to other’s advice (anyone see the irony here?)

- Define success for yourself before you go seeking it.

- Focus on your vision and do not imitate others.

- Understand the role of equipment and processes, they are subservient to vision and the simplest tools can produce incredible images!

- Be honest and sincere, these qualities have much more to do with being a good artist than most people understand.

Nathan: Are there any artistic influences outside of photography that have inspired your work– for example, painters, poets, writers, films, music, etc?

Cole: Yes, several.

- The Poem Invictus – My success is not dependent upon others; “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”

- The music of The Beatles – it reminds me to not to keep producing the same type of work simply because it was successful, in an attempt to remain successful. Experiment, grow, change, and shake it up!

- The novel The Fountainhead – It taught me to not care what others think, to follow my own vision, to define success for myself, to be independent.

- Edward Weston – I learned from Weston to not care what others think of my work, in creating the images my obligation to the viewer is complete.

- God – I believe we all have been given unique talents and that we should develop them. I have always believed that I was destined to be a photographer and artist.

Nathan: Do you listen to music when you process your photos? If yes, what do you listen to. And does music play a significant role in your creative process?

Cole: Yes I do listen to music while I work, I have splurged and installed a nice system in my office. As we write this I’m listening to the Alan Parsons Project. My library consists of 60?s and 70?s music, Jazz, Classical and Latin.

I’m not sure if listening to music while I process my work helps or not, but I do enjoy it!

Nathan:Any last thoughts or anything you would like to add?

Cole: I know that not everyone will agree with all of my ideas. Despite how I might come across, I am not advocating that this is the “right way” or that my approach is right for everyone. This is simply what I have learned and what I now believe. So I hope that nothing I’ve said has offended someone who believes or practices differently.

Who knows, in a few years I may look back to what I’ve said here and think “what a load of horse crap!”

Nathan: Now that we have talked about your vision, process and other thoughts about photography, I’d like to end with the beginning and the future: when did you first become involved with photography? What first inspired you? And do you have any specific direction you would like to take your work in the coming years? I’ll also take this moment to thank you for doing this, Cole. It’s been a pleasure to read your responses. I look forward to seeing where you take your work in the days, months and years to come.

Cole: You’ve always been so kind and supportive of me, Nathan, thank you. I enjoyed meeting you last year in Palo Alto. In this Internet age I’ll often “know” someone for years before I ever meet them! And thank you for asking me to talk with you about these things, I always enjoy expressing my thoughts because this process helps me refine my beliefs.

I discovered photography at age 14 and immediately knew that I was destined to be a photographer. I was out hiking with a friend in Rochester, NY when we came across an old ruin. My friend told me that the home had once been owned by George Eastman, the father of Kodak and in many ways the father of modern photography. This piqued my interest and so I checked out Eastman’s biography from the school library. I was fascinated by the story of photography and before I had finished the book, before I had taken a picture or watched a print come up in the darkroom, I knew that I would be a photographer. I felt destined.

I know that sounds silly and perhaps presumptuous, but it is honestly how I felt and have continued to feel throughout my life. This feeling of destiny started a 10 year intensive journey of personal study and self-education. I am self taught, I’ve never taken a photography class or workshop in my life. I literally spent every waking moment either reading and learning technical processes, working in the darkroom or studying the images of the great masters of photography. I was drawn to the work of Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Paul Strand, Wynn Bullock, Paul Caponigro, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham and others. I noticed that I was drawn to a particular type of image, dark images and contrasty images. When I’d see an image that struck me, I’d get this chill that would run down my spine. I wanted so badly to be able to create images like that and I worked hard to learn to do that.

Over the years my goals have changed and will probably continue to develop. Instead of wanting to be a photographer, I wanted to become an artist who used photography. Instead of documenting, I wanted to create. Instead of copying others, I wanted to find my own vision. Instead of being famous, I wanted to please myself.

What direction do I want to go in the future? I want to continue to try and see uniquely, to find joy in creating, and to combine my desire to see the world with my desire to create art

In so many ways I feel I am the luckiest person in the world.

Explore More of Cole’s Photography: website | blog | newsletter | emai

All images on this page– unless otherwise noted– are protected by copyright and may not be used for any purpose without Cole Thompson‘s permission.

The text of this interview is also protected by copyright and may not be used without the permission of Nathan Wirth or Cole Thompson.

September 20, 2012

I’m back from my annual retreat in Bandon, Oregon. It’s a very small town and I think it’s the most beautiful and unique spot on the entire Oregon coast. I go there each year for about 10 days to photograph, to be alone and to contemplate. I found some wonderful new dunes on this trip and the Gods of wind and weather smiled favorably upon me. Here is a new “Dunes of Nude” image I created while on this trip.

~

I mentioned that one of the reasons I go to Bandon each year is to be alone and think. Here are some of the thoughts I had while on this trip:

- It’s amazing that birds can fly.

- Driving alone for miles on the beach is great fun.

- Life is very short. The older you get, the shorter it seems.

- Fog can come in very, very quickly.

- I don’t trust people who don’t like dogs.

- As much as I love photography, I’m not sure how important it is in the larger scheme of things.

- Why do we spend so much of our lives caring what others think?

- Halibut fish and chips; much more expensive than Cod, but worth it.

- Teenage daughters are difficult to understand.

- Two “thumbs up!” to El Sombrero in Coos Bay, Oregon.

~

Yesterday I had my interview with Brooks Jensen for LensWork Extended. It’s always nice to talk with Brooks because he’s so down to earth and pragmatic. But in truth I always feel intimidated because of my lack of knowledge of art and “art talk.” I am unschooled in such things and simply know what I like.

~

Tomorrow (Saturday) I’m off on another trip and hope to see some new images. I say “see” because I know the images are there, it really is just a matter of being able to see them!

Aloha.

September 7, 2012

![]()

Zocalo Public Square recently hosted a discussion on “Idea Theft” and asked me to participate.

Up for Discussion

Theft Is In the Eye Of the Beholder

When Is It OK For Someone in Your Field To ‘Steal’ an Idea?

Did Samsung violate Apple’s intellectual property rights by making a phone with a pinchable screen? Should one-click online ordering be an idea owned by one corporation? Should the day come when Mickey Mouse belongs to everyone? Can Chinese companies make shoes featuring a swoosh? At what point would our paraphrasing of someone else’s paraphrasing of what someone else said amount to plagiarism?

Our culture, our laws and our technologies are all grappling these days with the meaning of intellectual property and the boundaries between improving upon past innovations, and misappropriating them. In advance of the Zócalo event “Does Imitation Breed Innovation?” we asked five artistic minds to ponder when it’s OK for someone to steal an idea.

The case for artistic celibacy

Most of us would never steal an object…but the issue is not so simple or clear when we’re talking about something as intangible as an idea, especially in art. If someone were to copy an image from the Internet and put their name on it, we’d all call that stealing. But what if someone creates an image that uses a similar look, style, technique or subject matter to mine…would that be stealing? And what if upon investigation I found that the other artist’s work had pre-dated mine or that they were unaware of my work?

This has happened to me several times. Sometimes the work had been developed in parallel, with each of us unaware of the other’s work. Sometimes the other person’s work had pre-dated mine, and sometimes people loved my idea and were simply imitating it. All art is evolutionary, some say, built upon the work that comes before.

Ultimately I came to the conclusion that I cannot determine the difference between stealing, copying, imitating, working in parallel or building upon another’s work. Most importantly, I shouldn’t care! As an artist I need to stay focused on what I am doing and not what others are doing. Not only would that be a waste of time, it would take energy and focus away from my art. My job as an artist is to create as uniquely as possible and I personally do not wish to build upon the work of others.

To facilitate seeing uniquely, I have been practicing “Photographic Celibacy” for the last five years. It is the practice of not looking at other photographers’ work. I do this to minimize the influence others have on my art and to reduce my temptation to “copy” them. I personally find the unconscious inclination to imitate to be destructive to the creative process.

Cole Thompson is a black-and-white fine art photographer living on a small ranch in Northern Colorado. He began creating at age 14 and has always worked in black and white. He is often asked, “Why black and white?” His answer: “I think it’s because I grew up in a black-and-white world. Television, movies and the news were all in black and white. My heroes were in black and white and even the nation was segregated into black and white. My images are an extension of the world in which I grew up.”

—————————————————————————————————————

How can you not copy a classic drink?

It’s never acceptable to take from another and claim it as your own, although in the tight-knit fraternity of cocktail mixing, ideas and past traditions are widely celebrated and emulated.

Today it is en vogue to be a bartender. However, for a long time bartending was not considered to be a professional end goal. In fact we had been considered downright disreputable. That’s one reason we celebrate those who came before us, who taught us everything we know and inspire us to be better and question the received wisdom. This questioning spawns conversation or variations. The same thing is done in literature, for example when James Joyce wrote Ulysses he wasn’t stealing from the Odyssey but rather having a conversation with Homer.

We too are storytellers but with drinks. When we make a variation of a classic and don’t tell the story behind the drink we rob our guests of a rich and enduring connection that they can in turn share with others. I am no different than you when I walk into a bar. When it is a bar manned by someone I like and respect, I am filled with an excitement that borders on mania. I feel the same way every time I make a drink I love, I can’t help but tell the story of that drink and when I slide it over to my guest in my mind there is diffused lighting and Teddy Pendergrass playing because that is love.

Zahra Bates is head bartender at Providence Restaurant.

—————————————————————————————————————

True stealing is better than borrowing

It depends what’s meant by the word “steal.” It’s never OK for someone to literally steal something, however the question usually isn’t one to take literally. An idea itself isn’t what’s valuable. It’s how the idea is implemented that creates value.

In Web design, as in any industry with a creative component, people copy each other’s ideas all the time. Sometimes these ideas have become so much a part of the standard or the convention that not using them would lead to a less effective design. For example, most people expect to arrive at a website and find a list of links across the top or down the side that serves as global navigation. On the other hand, exactly how one designer crafts a navigation bar isn’t part of that convention.

There’s a famous quote attributed variously to Picasso, Stravinsky and others, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal,” which is often misunderstood, but applies well to this question. When you borrow something, it’s not yours. You plan to give it back. When you steal something, you make it yours. It’s this notion of making it yours that’s the important part of the quote.

The proper way to steal an idea in design or any industry is to make it your own. Take it apart. Understand what makes it a good idea. Assimilate it and internalize it. Mix it with all the other ideas within you. Something new will arise from the combination of the ideas within and the idea you’ve stolen.

That new idea may recognizably come from the idea you’ve stolen, but it won’t be the same. It will be improved. It will be different. It will be something of your own. When you steal ideas in this way you add to them and contribute to your industry. If all you do is copy them outright you’ve only taken something that doesn’t belong to you.

Steven Bradley is a web designer and WordPress developer who moved to Boulder, Colorado to be near the mountains. He blogs at Vanseo Design and owns and operates a small business forumhelping people learn how to run and market their business more effectively.

—————————————————————————————————————

Fashion, the ultimate minefield

I work as a professional fashion illustrator. I am also an enthusiastic, non-professional fashion blogger. Of these occupations, illustration is more clearly governed by law when it comes to intellectual property. Although I’ve discovered that explaining the nuances of copyright to clients unfamiliar with the concept is so confusing in the digital age, the conversation can be counterproductive to developing relationships and doing business. This means that my business is often run more on intuition and good faith than on contract. As an illustrator who works in the fashion industry, my laissez-faire approach to enforcing my own copyright would horrify illustrators who work in traditional publishing. But, with my limited time on Earth, I’d rather draw than practice the law.

Fashion blogging is a virtual Canal Street of grey-market intellectual property violation. A lot of this is lazy blogging—just appropriating other people’s creations. Then there are a few clever bloggers who are combining images and ideas in startling new ways, creating a fascinating and viral universal cultural pulse.

When is it not OK to take an idea? That may be the more interesting question. I believe the answer relates to power dynamics. When a wealthy corporation profits off the idea of an independent creative, something feels unjust about that. But if a teenager somewhere throws an appropriated image up on their Tumblr, logging it into the stream of consciousness of modern youth, throwing the book at them just seems petty… and old-fashioned.

Danielle Meder is a fashion illustrator. She blogs at Final Fashion.

—————————————————————————————————————

Ideas can’t be locked up

“A great artist never borrows; he steals.” Variations on this insinuatingly provocative quip have been ascribed to so many artists—including Balanchine and Stravinksy, to name only two prominent figures in my field, which is dance—that it is impossible to know who originated it. The remark itself appears to have been borrowed—or stolen—multiple times. The point: that an idea completely appropriated, digested, and re-presented by an artist is not merely borrowed but transformed, and therefore rightly owned. If that is true, then stealing is always acceptable—and a prerogative of greatness.

The problem of “stealing” arises only when an aggrieved artist alleges that this taking-and-changing process has been insufficiently transformative, especially when there is prestige, career advantage, or, above all, serious money involved. Anxieties over influencing versus being influenced are sharpened to the point of drawing blood when more than a given instance of influence per se lies at stake. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery only until someone else is getting royalties—or selling at auction prices—you think rightly yours.

Artists of the past would find our modern attitude to ownership of ideas strange, to say the least. In Shakespeare’s day, for example, the notion barely existed, if at all. If Shakespeare were our contemporary, he would likely find himself embroiled in a lawsuit for copyright infringement with the chronicler Hollinshed, whose prose the playwright rather openly pillaged. In the words of one scholar, passages of several of Shakespeare’s history plays are more or less metrical transcriptions of Hollinshed into blank iambic pentameter. If that isn’t stealing, what is?

Of course, few would argue that the body of law that attempts to define intellectual property and copyright of artistic production should be abolished altogether. Nonetheless, if only for the sake of intellectual honesty and good faith, we ought to acknowledge how dubious, if not self-contradictory, it is to attempt somehow to define the expression of an idea (which is intrinsically protected by copyright) apart from an idea itself (which is not protected)—the key distinction that undergirds the whole legal apparatus.

In fact, the single most powerful driver behind the series of extensions of copyright beyond the death of the author has been the Walt Disney company, a corporate behemoth which has successfully pressured the US government to prevent Mickey Mouse from dancing into the public domain—Mickey, who, at his birth in 1928, really was a character, but who has long been reduced (or elevated) to the status of brand identity, corporate icon, and so on.

Ultimately, the whole concept of intellectual “property” that underlies the possibility of one artist’s accusing another of “stealing” an idea is rooted in the bourgeois attitude towards knowledge—which is entirely intangible—as a kind of thing. (I mean bourgeois in the historical sense of term, not, as the word is usually used vernacularly in the U.S., as a mere hip insult). The finer the distinctions made in any given lawsuit, the more a detached viewer may see the concerted attempts involved to shore up a giant castle built of sand. For ideas are not, and never really can be, things.

The deepest fear that flows beneath the whole discussion is not the fear of being insufficiently original, or of having our ideas stolen, or of some other artist’s making money that is rightfully ours. The immateriality of all mental activity, including all acts of artistic creation, is what terrifies and appalls and makes us all a little bit desperate. Ideas, ultimately, cannot be owned, borrowed, or stolen—and you can’t take them with you. What we really fear when we admit that we are afraid of having our ideas stolen is death: the howling, unimaginable silence that will ultimately engulf all we do or have ever done.

Christopher Caines is artistic director of Christopher Caines Dance. His most recently published writing is a commissioned essay on Antony Tudor for the Dance Heritage Coalition’s America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures online project. Upcoming performances include his company’s appearance at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City for the Feast of St. Francis/The Blessing of the Animals on October 7.

*Photo courtesy of cangaroojack. Photo of Danielle Meder courtesy of Matthieu Da Cruz.

August 31, 2012

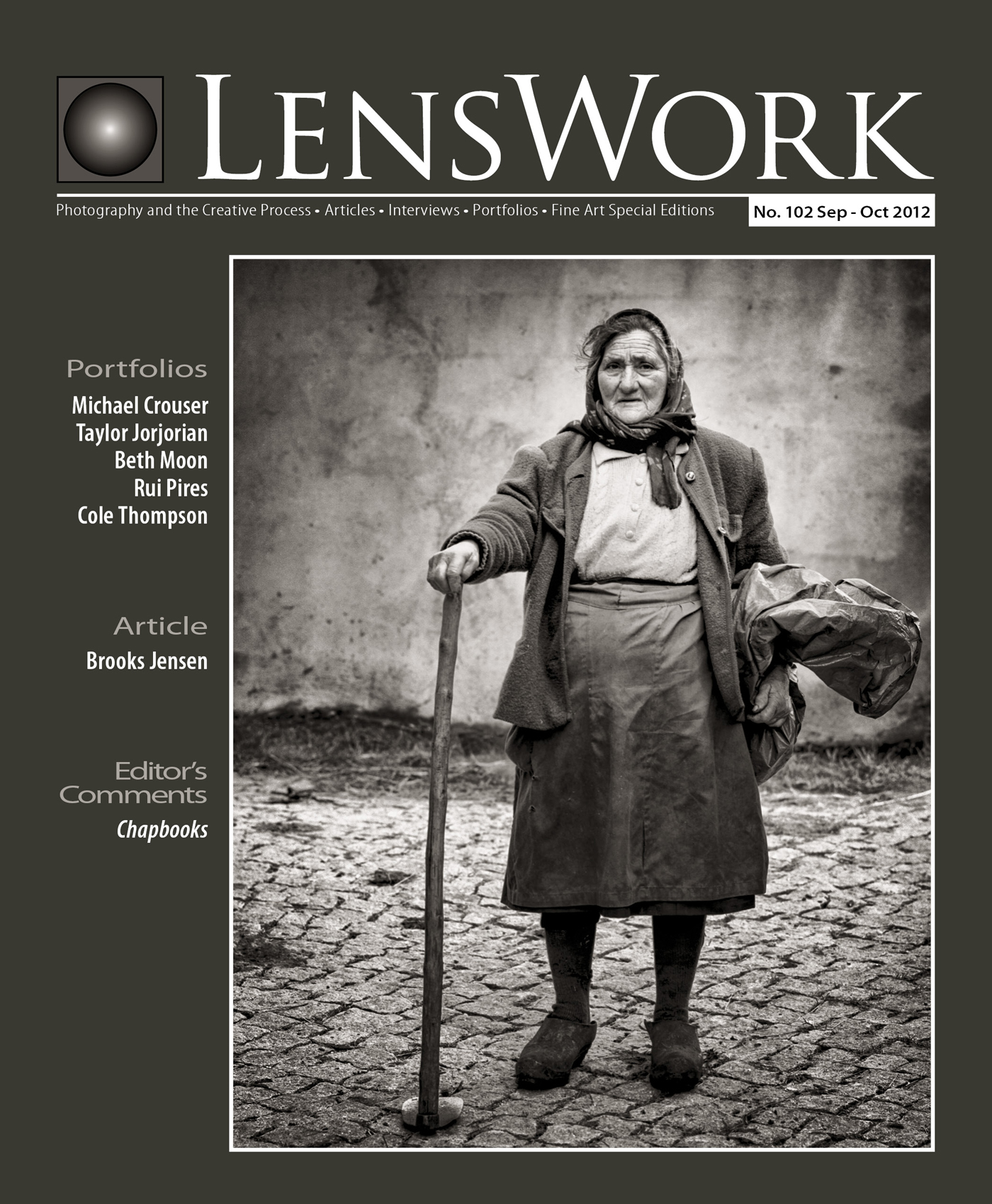

My portfolio “Death Valley: Where Time Stands Still” is featured in the current issue of LensWork. It is always an honor to be featured here.

If you’ve never seen a printed copy of LensWork, then you are missing out on one of the finest printed publications in the world. The quality of their duotone printing surpasses most of the photo books I own and the quality of their featured photographers is consistently high. And then there is LensWork Extended, a DVD with additional content such as audio interviews, additional images, video and even…dare I utter the word…color!

Something else I love about LensWork are the writings of editor Brooks Jensen. I have always liked his out-of-the-mainstream views and appreciated his common-sense wisdom about art and photography (even though we differ in opinion on “Photographic Celibacy!“)

So far I have had these portfolios featured in LensWork and LensWork Extended:

- Grain Silos

- Ceiling Lamps

- The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau

- Death Valley: Where Time Stands Still

Unfortunately you can no longer purchase LensWork on the newsstands, however you can purchase a copy or subscribe here:

http://www.lenswork.com/previewpages/lw102/lw102preview.html

If you were going to read just one photo publication, I’d suggest that you get rid of the ones that focus on equipment and subscribe to LensWork that focuses on art. At $39 a year, it is a steal and I’m not sure how Brooks Jensen can afford to do it!

Cole

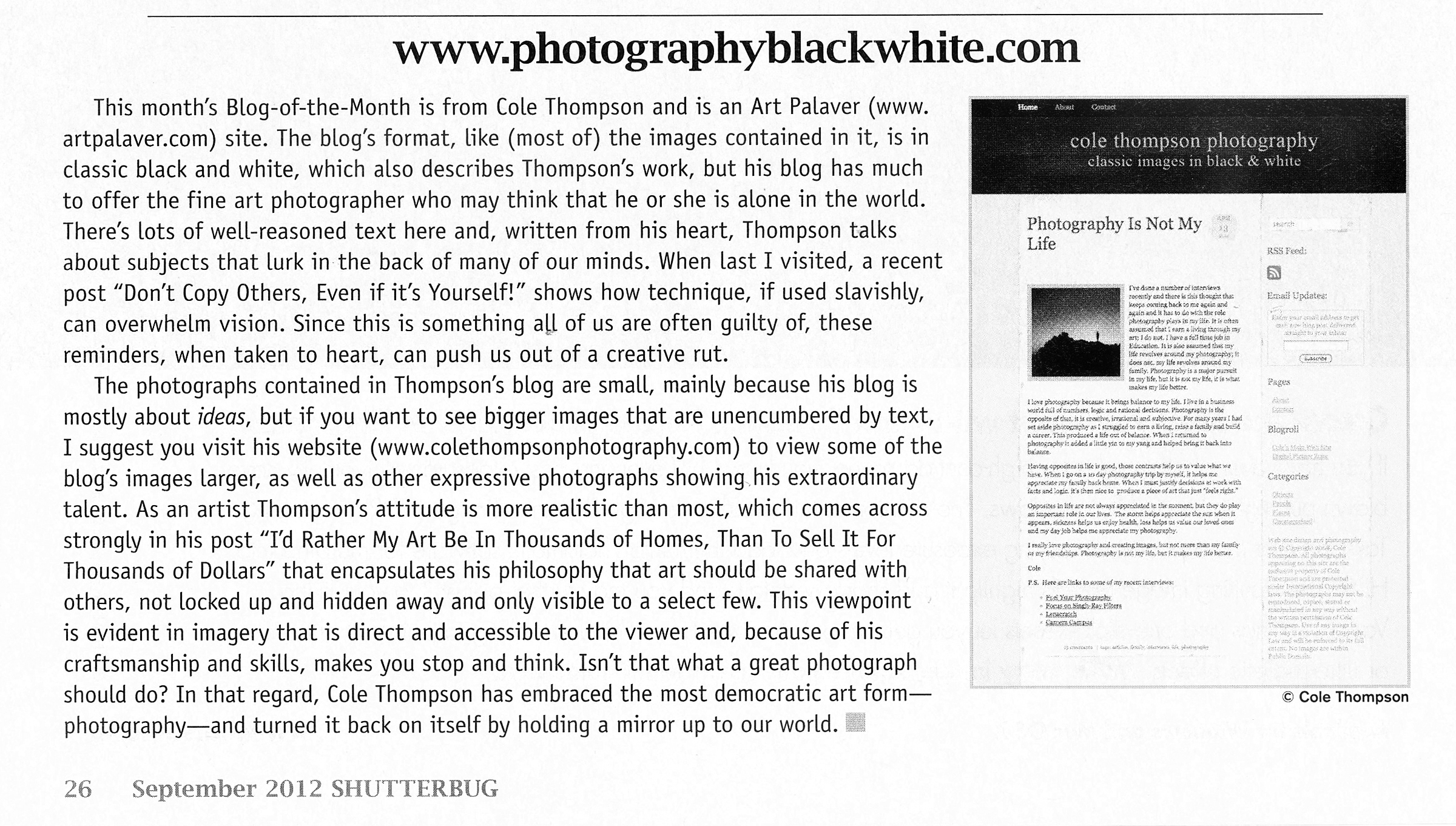

August 17, 2012

Joe Farace writes a column for SHUTTERBUG. I knew I was going to like Joe’s views and attitude when I saw this tag line:

“Ultimately, it’s all about the image…”

You can visit Shutterbug at http://www.shutterbug.com/

This month Joe introduces his readers to four new photographers, including myself and my blog.

Cole

July 28, 2012

I often tell people not to follow other people’s advice. However, if you follow this advice then you wouldn’t follow my advice…which would mean that you actually should follow my advice. What a conundrum!

Everyone loves to give advice; we all know how others should live their lives even better than we know how to live our own, and it’s no different with our art. Everyone wants to tell us how we should process our images and how we should best achieve success. The advice givers are good people, who are well intentioned and who have had some wonderful life experiences, so why shouldn’t you follow their advice?

Because their vision is different from your vision and their definition of success may be different than yours. Can you imagine what might happen if I was inclined to give you lots of advice and you were inclined to follow it? One day you might wake up to the realization that your images bore a striking resemblance to mine and that you had met every one of the goals that I had set for myself! It’s not that my advice is bad, it simply may not be right for you.

Over the years I’ve come to learn that the only opinion that really matters is your own. Let me illustrate with two examples of some well-intentioned advice that I’ve received:

Never Center the Image!

A few years back my friend and mentor saw my latest image entitled The Angel Gabriel and almost yelled “Never center the image!” I was frequently presenting her with centered images (see above) and she constantly told me that I was breaking one of the rules of photography. I respected her position and experience but the advice just didn’t feel right to me. However since she was the teacher and I the student, I reluctantly re-cropped the image as she had advised… and I just hated it! It literally made me ill to look at it and at that moment I realized that this was my image and my vision and no one could tell me how it should look. It wasn’t that her experience wasn’t good, but it came from her vision and it wasn’t right for me.

It is critically important that you find your own vision and once you do, you’ll find less and less of a need to ask others for advice about your work.

Large Prints, Small Editions:

I have a friend who is attempting to earn his living from his photography. He has chosen to offer large prints and very small editions (as low as 12). He believes this will maximize his profits and thinks my open editions and lower prices is a bad idea. He has frequently tried to convince me that I am making a mistake and that I should follow his example.

The problem with his advice is that he and I have different definitions of success and therefore different goals. I am not trying to earn a living from my art, I wouldn’t be happy in the Gallery environment and I couldn’t stand the thought of printing only 12 images and then never any more! This formula would not work for me, even though it may work for him.

It is so important that you define success for yourself. What do you want from your art? What will bring lasting satisfaction? In five years, what would you like to accomplish with your art? Only once you know the answer to these questions, can you set your own course with confidence.