Category: Philosophy

July 4, 2014

I was exhibiting my “Ancient Stones” portfolio when someone approached.

We both stood there looking at the images when he said: “You just cannot do b&w work like this with digital!”

I didn’t have the heart to tell him, but thought of this anecdote:

“A photographer went to a socialite party in New York. As he entered the front door, the host said ‘I love your pictures – they’re wonderful; you must have a fantastic camera.’ He said nothing until dinner was finished, then: ‘That was a wonderful dinner; you must have a terrific Stove.'” Sam HaskinsJune 14, 2014

I have been thinking about two words lately: visualize and previsualize. What do they mean and how are they different?

I’ve used both words to describe my creative process and yet I’m not really sure if I’m visualizing or previsualizing?

So I looked them up in the dictionary:

Visualize: form a mental image of; imagine.

Previsualize: The word you’ve entered isn’t in the dictionary.

Hmmmm…so previsualize is not a “real” word?

I then turned to the ultimate authority of the universe (Wikipedia) to see what I could learn about previsualization. Here is what I found:

Visualization is a central topic in Ansel Adams‘ writings about photography, where he defines it as “the ability to anticipate a finished image before making the exposure”.

The term previsualization has been attributed to Minor White who divided visualization into previsualization, referring to visualization while studying the subject; and postvisualization, referring to remembering the visualized image at printing time.

However, White himself said that he learned the idea, which he called a “psychological concept” from Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

According to Adams and White, visualization and previsualization are the same and this process takes place before the exposure.

This has been my experience, that visualization takes place before the exposure. When I’m looking at the subject I can literally see the final image in my “mind’s eye.”

This Vision typically comes quickly and definitively and it guides me during the shot and the processing, helping me transform the captured image into to that visualized image. There is no question as to what the final image will look like, it is burned into my memory.

Inspiration may come after the exposure and during processing, but that would not be visualization according to Adams or previsualization according to White’s thinking.

I’m grateful for the inspiration whenever it may come, but I do find it most useful when it comes before the exposure.

What has your experience been with visualization or previsualization?

Cole

May 9, 2014

The Angel Gabriel

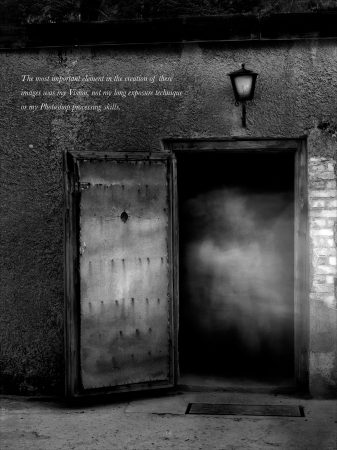

Why do I focus on Vision so much? It’s because I believe that Vision is what makes an image great. It’s what makes the difference between a technically perfect image and one with feeling. It’s what makes your images unique.

Great images do not come about because of equipment and processes, but rather from Vision that drives these tools to do wonderful things. What good are great technical skills if you don’t have an idea worthy of them?

If I had to choose between the best equipment in the world and no Vision or having a Kodak Brownie and my Vision…

I’d take the Brownie.

A lot of people ask: “How do I go about finding my Vision?” I’m not sure I can answer that for everyone, but here is how I discovered mine:

The Wake-Up Call

Several years ago I was attending Review Santa Fe where over the course of a day my work was evaluated by a number of gallery owners, curators, publishers and “experts” in the field.

During the last review of a very long day, the reviewer quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back to me and said “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I replied that I was, because I loved his work! He then said something that would change my life:

“Ansel’s already done Ansel and you’re not going to do him any better. What can you create that shows your unique vision?”

Those words really stung, but over the next two years the message did sink in: Was it my life’s ambition to be known as the world’s best Ansel Adams imitator? Had I no higher aspirations than that?

I desperately wanted to know if I had a Vision, but there was a huge problem: what exactly was Vision and how did I develop it?

I researched Vision but I couldn’t relate to the definitions and explanations that I found. Was it a look, a style or a technique? Was it something you were born with or something you developed?

And then there was the nagging doubt: what if I didn’t have a Vision? I feared that it was something you either “had” or you “didn’t have” and perhaps I did not?

And how was I to go about finding my Vision?

With so many unanswered questions and with no idea on how to proceed, I simply forged ahead with what made sense to me. Here is what I did:

1. Sort Your Portfolio

I took 100 of my best images, printed them out and then divided them into two groups: the ones I REALLY loved…and all the rest. I decided that the ones that went in the “loved” pile had to be images that “I” loved, and not just ones that I was attached to because they had received a lot praise, won awards or sold the best. And if I loved an image and nobody else did, I still picked it.

2. Make the Commitment

I committed that from that point on, I would only pursue those kinds of images, the ones that I really loved. Too often I had been sidetracked when I chose to pursue images simply because others liked them.

3. Practice Photographic Celibacy

I started practicing Photographic Celibacy and stopped looking at other photographer’s work. I reasoned that to find my Vision, I had to stop immersing myself in the Vision and images of others.

I used to spend hours and hours looking at other photographer’s work and would find myself copying their style or even their specific images. I knew that I couldn’t wipe the blackboard of my mind clean of those images, but I could certainly stop focusing on their Vision and instead focus on mine.

When I looked at a scene I didn’t want to see it through another photographer’s eyes, I wanted to see it through mine!

4. Simplify Your Processes

I embarked on a mission to simplify my photography. In the past I had focused on the technical and now I was going to focus on the creative. I disposed of everything that was not necessary: extra equipment, gadgets, plug-ins, programs, processes and all of those toys we technophiles love. I went back to the basics which simplified my photography, gave me more time and it reminded me that I wanted to put more focus on my creative abilities.

5. Ignore Other’s Advice

I ignored the advice that well intentioned friends and experts gave me. So much of this advice had never felt right for me and I was torn between following their recommendations or my own intuition. In the end I decided that only by pleasing myself could I create my best work, and that no matter how expert someone was, they were not an expert about my Vision or what I wanted.

6. Change Your Mindset

I worked to change my mindset from photographer to artist. I had always thought of myself as a photographer who documented, but I could see that this role was limiting and the truth was that I wanted to be an artist that created.

To help me make this mental shift I started calling myself an artist (I felt like such a fraud at first) figuring that I must play the part to become the part. I also stopped using certain words and phrases, for example instead of saying “take a picture” I would say “create an image.”

That may seem like small and inconsequential thing, but it helped to continually remind me that I wanted to be an artist who created, and not a photographer who documented.

7. Question Your Motives

I questioned my motives and honestly answered some hard question such as: why am I creating? Who am I trying to please? What do I want from my photography? How do I define success?

It seemed to me that Vision was something honest and that if I were going to find my Vision, I had to be honest about the reasons I was pursuing it.

8. Stop Comparing

I stopped comparing my work to other photographers. I noticed that when I compared, it led to doubts about my abilities and it left me deflated. All I could see were their strengths and my weaknesses, which was an unfair comparison.

I decided that if my goal was to produce the best work that I could, then it did not matter what others were doing. I had to remind myself that this was not a race or a contest, I was not competing against others…I was competing with myself.

9. Stop Caring What Others Think

I made a conscious decision to stop caring what others thought of my work. I recognized that in trying to please others, I was left feeling insecure and empty.

At the end of the day, it was just me, my work and what I thought of it. As long as I cared what others thought, I was a slave and could never be free.

10. Get Inspired

I re-read Ayn Rand’s novel “The Fountainhead” which I had first read at age 17. It has been one of the most influential books of my life because it gave me hope that I could become truly independent, that I could think for myself and define my own future. I know this book can cause strong reactions in people, both for good and ill, but it was a tremendous help in finding my Vision.

~~~~~~

I really was proceeding blindly, but I believed that if I listened to my own desires, pursued what I loved and eliminated all other voices, I would learn something about my Vision.

I did this for two years and there were many times that I became discouraged and didn’t feel like I was making any progress. I didn’t really know what I expected to happen, perhaps I thought I’d have a revelatory experience where my Vision would suddenly appear in a moment of inspiration!

But that didn’t happen.

And then one day it just occurred to me: I understood…I understood what my Vision was.

It came in an anticlimatical and quiet moment of understanding, and after all of that worrying and angst…it now seemed so incredibly simple. Vision was not something I needed to acquire or develop, it had been there all along and all that I needed to do was to “discover” it.

Vision was simply the sum total of my life experiences that caused me to see the world in a unique way. When I looked at a scene and imagined it a certain way…that was my vision.

My Vision had always been there but over the years it had been buried by layers of “junk.” Each layer obscured my vision until it was lost and I doubted my creative abilities. Some of those layers were valuing other’s opinions over my own, fear of failing, imitating others and creating for recognition.

Each time I created for external rewards, each time I put accolades before personal satisfaction, each time I cared what others would think…I buried my natural creativity under another layer until it was buried and forgotten.

Interestingly I came to conclude that Vision had little to do with photography or art and had more to do with being a well-adjusted, confident and independent human being. Once I had the confidence to pursue my art on my terms, and define success for myself, I was free to pursue my Vision without fear of rejection or need for acceptance.

Something else I learned about Vision: it is not a look or a style. It is not focusing on one subject or genre and following your Vision will not make your work look all the same. Vision gives you the freedom to pursue any subject, create in any style and do anything that you want.

But finding my Vision was not the end of the journey, because now I had to follow it which was equally as hard. I am still tempted to create for recognition, to care what others think and to want to be acknowledged. It takes constant discipline to stay centered, to remember why I’m creating and to follow my definition of success.

If you could have known me before I found my Vision, you would have found a technician that doubted his creative abilities, a photographer who felt that it was wrong to “manipulate” the image, a person who sought the generally accepted definition of success: money, fame and accolades, and you would have found an insecure person who needed others to like his images in order to feel good about his work.

Thankfully, that person is gone.

While my initial search was for my Vision, what I really found was myself which allowed my natural Vision to flourish once again.

Cole

March 1, 2014

I don’t wish to offend anyone, but watermarks drive me crazy!

I find them distracting and it ruins the viewing experience for me. I’m not sure which is more offensive, the transparent ones that go completely across the image or the bright white ones in the corner of the image.

Imagine if you printed your work with the watermark, how do you think it would affect the viewing experience? Not well, and now that most viewing of images takes place online, you are ruining a lot of viewing experiences!

Presumably it’s done to stop people from stealing your image, but I’ve never personally had a problem with this. What would they do with it, it’s low resolution and not suitable for printing. Or do I think they will use my image and claim that it’s theirs? I’ve never seen that happen, to anyone.

I think the worst thing that is likely to happen is that someone could use my image without giving me credit for it, but even if that occasionally occurs, no harm is done. I once found an online auto parts store using my “Old Car Interior” image above, I love free exposure and so I simply wrote and asked them to give me credit for the image.

Now, let me turn this personal rant into something useful. How can you know if someone is using one of your images? There is a very simple method using the Google search function. Using a technology similar to facial recognition, you can upload an image and have Google tell you everywhere that it’s posted. It’s very cool!

Here’s how you do it using Chrome (and I assume it’s the same with other browsers):

- Go to google.com and it will display a search window

- Choose “Images” in the top right corner

- Now, instead of typing something into the search window, click on the little camera over on the right side of the search window.

- Paste or upload the photo that you want to search for (you can use mine above)

- Click on the search logo and see everywhere this image appears.

If you’re concerned about people stealing your images, this is an easy way to confirm if it’s a problem or not. But I’m guessing it’s not.

Now back to my rant: watermarks are distracting and unnecessary…think about it!

Cole

February 25, 2014

Ancient Stones No. 23 – Alabama Hills – 2014

In the beginning was the scene, and the scene was good.

But not everyone could see the scene, and so man invented photography so that all could enjoy the beauty.

And then other men invented the art expert. The experts did not think it was enough to simply see the beauty of the scene, they needed to describe the scene and tell us what it meant.

And that was not good.

~ ~ ~

We like to say that a picture is worth 1000 words. So why do some feel the need to describe a beautiful image with a few paltry words?

People ask me “what are you saying with your image?” and I respond: “look at it, what is it saying to you?”

The words from Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy the Silence” echo in my head:

All I ever wanted

All I ever needed

Is here in my arms

Words are very unnecessary

They can only do harm

Enjoy the image, enjoy the silence.

Cole

February 19, 2014

The so-called rules of photographic composition are, in my opinion, invalid, irrelevant, immaterial.

Harbinger No. 16 – 2014

Ansel Adams said: “The so-called rules of photographic composition are, in my opinion, invalid, irrelevant, immaterial.”

And I’ll go one step further and say that in my opinion these rules are actually harmful because they get in the way of developing creativity and Vision.

For years I’ve rebelled against the rules of photography. Why? Because my experience has taught me that they encourage dependency and discourage independent seeing.

I’ve had people criticize my images because they didn’t follow some imaginary rule of composition and I thought: how sad that when they look at this beautiful image, all they can see are the rules. That’s called not being able to see the forest for the trees.

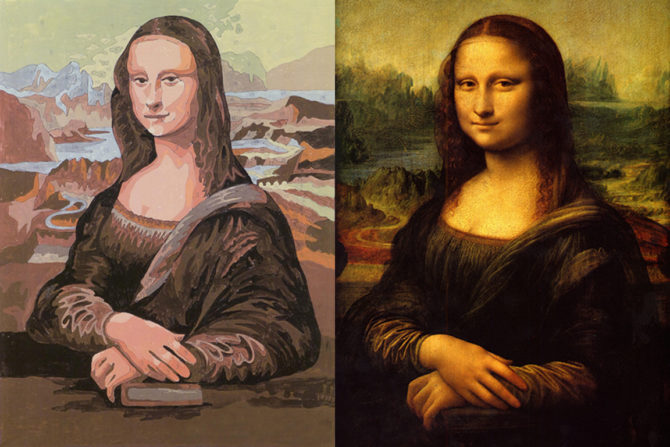

The rules of composition is an attempt to distill the creative process into a series of simple guidelines that if followed, will produce a good image. It reminds me of the old “paint by numbers” painting kit: simply put the proper color into each numbered area, stay within the lines and you’ll have a “real” painting! Yes, but it’s not a very good painting and it’s certainly not an original.

Do you remember IBM’s Deep Blue computer? It was programmed to play chess and it beat the world champion chess player, Garry Kasparov. Do you think that if we were to program the rules of photography into Deep Blue and take it to Yosemite, that it could beat Ansel Adams?

Of course not, because composition is about seeing and feeling, not about following rules. And the irony of these rules is that they are supposed to help you learn to be creative, when what they actually do is cause dependency.

I love travelling with a GPS because I can plug in an address and it gives me turn-by-turn directions. But I’ve noticed that there’s a negative side effect that comes from relying on my GPS: I’ve become so dependent upon it that I cannot find anything without it, even in cities that I frequently travel. The GPS has made me so myopic that I’ve never developed the big picture of the city.

That’s what I believe happens when you rely on the rules of composition: you become myopic and dependent. You don’t develop the big picture, you don’t see for yourself, you don’t trust your own feelings.

“So Cole, if I shouldn’t follow the rules, how do propose that I learn to compose an image?”

I like the Professor Harold Hill approach, do you remember him? He was the likeable charlatan from The Music Man who rode into River City, Iowa selling band instruments. He taught the boys in town how to play their instruments using the Think System, that’s where you “think the notes and just play the notes.” It sounds silly, but I think there’s a lesson to be learned from this approach!

When I approach a scene, I simply look and see and feel. I compose instinctively until the scene feels right, without a single thought about the “rules.” And if the composition doesn’t feel right, I change it. I move the camera, I zoom in, I try another angle…but in the end all I care about is that it “feels right.” Does that sound as silly as Professor Hill’s Think System?

And after I’ve created the image, I don’t ask others what they think and I don’t listen to the “experts” who will tell me how I should have done it. I trust my instincts and remember that I’m learning to express my vision and not theirs. Learning to trust your instincts is one of the first steps in the creative process.

What a simple and empowering concept: to see and feel for yourself rather than following the rules. Creative people already know this secret: that great art comes from within and is not found in a set of rules.

Start by believing in yourself and your own inherent creativity. Then forget about the rules. Next comes practice, practice, practice and evaluating each image by asking yourself: “what could I have done differently to make this image better?” And most importantly, rely on your own opinion and don’t ask others what they think of your images.

This approach is not an easy shortcut, it’s a long and hard process in which you’ll create thousands of failures. But with each failure you’ll get better and most importantly, you’ll be creating originals and not “paint by number” counterfeits!

Cole

P.S. Here’s a test question: I have friends who ask me “how will I know if I have a good image if I don’t ask other people’s opinion of it?” How would you answer this?

January 23, 2014

“A photographer went to a socialite party in New York. As he entered the front door, the host said ‘I love your pictures – they’re wonderful; you must have a fantastic camera.’

December 19, 2013

Balance No. 1

I recently taught a workshop on Vision and was discussing my practice of Photographic Celibacy. I explained that the reason I do not look at other photographer’s work is that I don’t want my Vision to be tainted by the vision and images of others. And while that is completely true, there is another reason that I am embarrassed to admit: when I look at other people’s work, I doubt my abilities and get discouraged.

When I see all the many wonderful images out there, I feel mine are inferior by comparison. When I see the great images from locations that I have photographed, I am disappointed that I did not see them. I am overwhelmed by the sheer number of great photographers out there and think: there’s no room left for me. I feel inadequate when I see so many original ideas…that I did not think of.

And so I get depressed at the thought of competing with all of these great images and photographers.

But therein lies my mistake: creating art is not a competition and I should not compare my work to others. I am not trying to be better than someone else, I am trying to better myself.

Everyone has the ability to be great at something, but I cannot be great at all things. I cannot be a a great portrait photographer, a great landscape photographer, a great street photographer, a great floral photographer and a great still life photographer. But there is something I can be great at, and I cannot achieve that greatness by focusing on what I’m not good at. I must recognize my talents and be appreciative for those.

I need to remember that art is not a competition. When I create from my vision there are no losers, only winners.

Cole

P.S. I used to think I was alone in having these feelings, but as I have shared these thoughts with others (including some big name photographers) I’ve learned that many feel the same way. We are all human and share the same frailties, foibles and insecurities. No matter who we are, it seems to be human nature to compare ourselves to others and to sometimes feel inadequate.

December 14, 2013

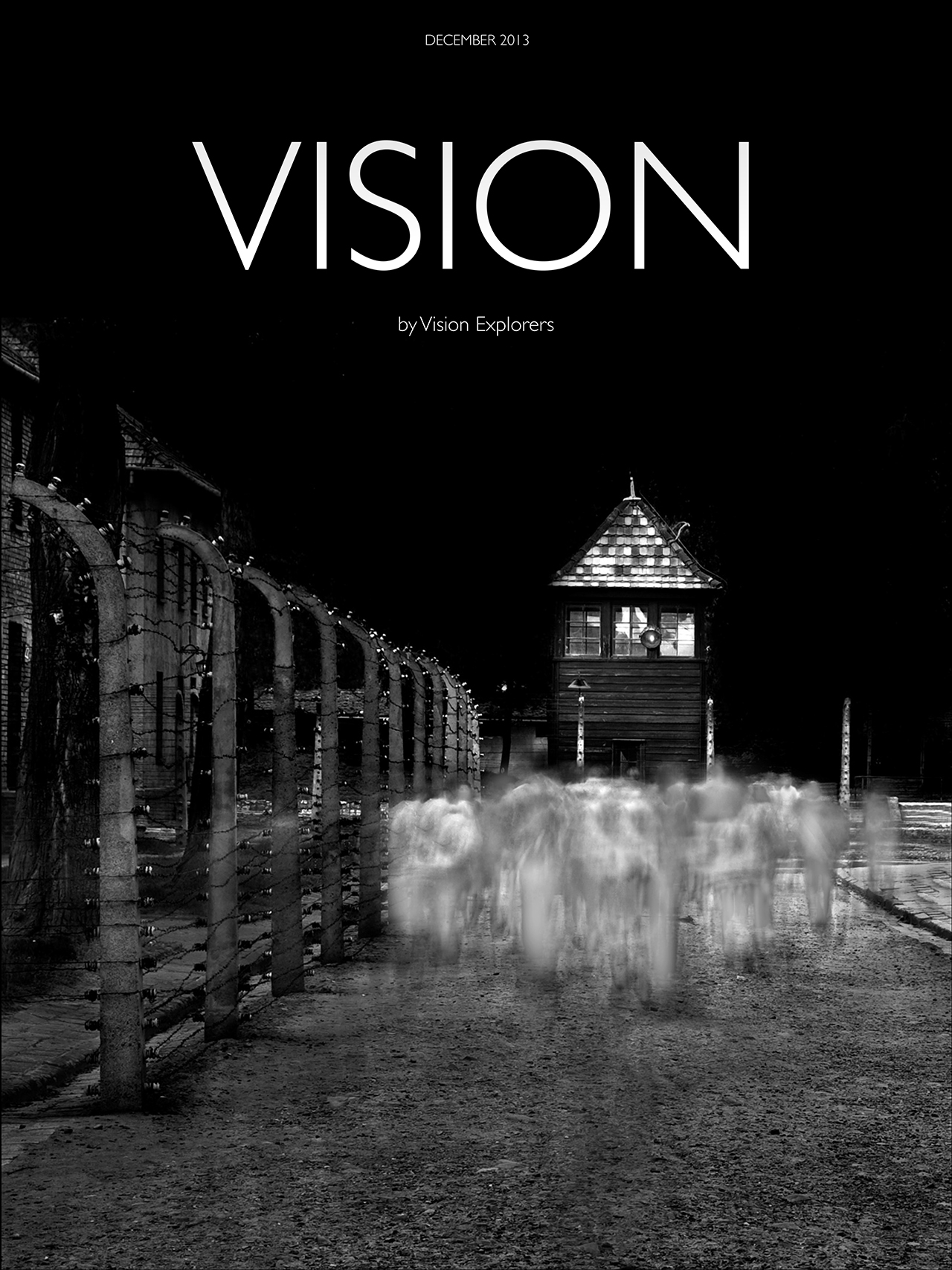

Are you familiar with the new publication Vision? It’s produced by friends of mine: Joel Tjintjelaar, Sharon Tenenbaum, Armand Djicks and Daniel Portal.

What I love about this beautifully simple magazine is that it focuses on Vision rather than equipment, processes and techniques. Here’s a great quote from their website:

“You are an artist before you are a photographer”

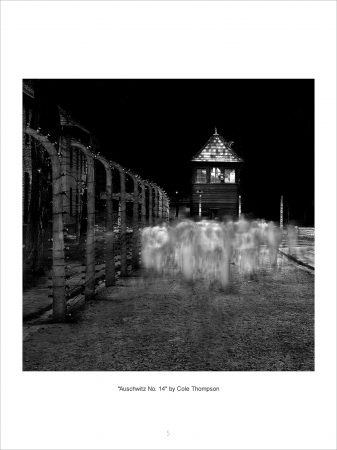

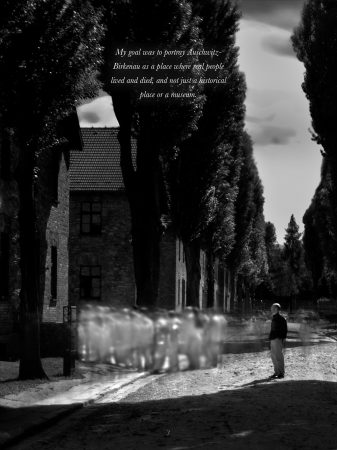

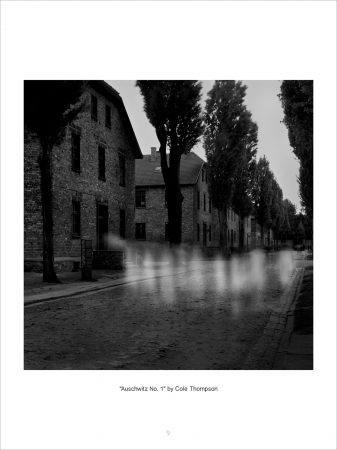

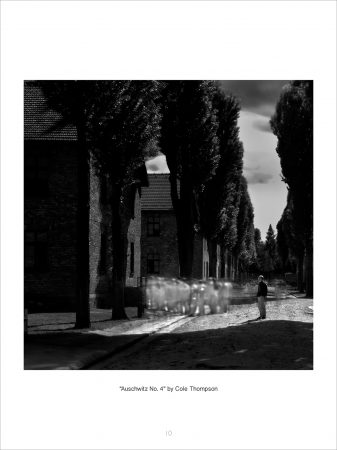

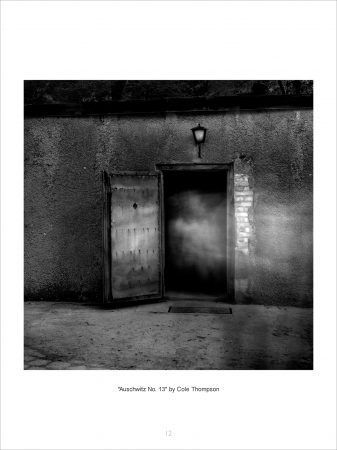

Because we share such similar views on vision, they asked to speak with me about the vision that created “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau.” The interview is in the December 2013 issue.

Vision is a relevant and important publication for those who seek to improve their creative abilities. Vision is free and you can subscribe here: http://visionexplorers.com/magazine/

You can view and enlarge the individual pages of the article below, or you can View the Entire Article Here

August 31, 2013

Dunes of Nude No. 89

There are so many times that have people said to me: to be successful you must…

focus on one thing and be known for that

promote yourself

get in a big name gallery

publish a book

be active in social media

get reviewed

be number 1 in SEO

offer small limited editions and high prices

create unique work

etc, etc, etc.

Here’s the problem: how can anyone give relevant advice if they don’t know what my definition of success is?

And more importantly, how can I pursue success if I don’t know what success means to me?

I didn’t ask myself “what is success” until many decades into my career, and what I discovered was that I didn’t like the standard definitions.

I found them to be unfulfilling.

So…take a few minutes and define what you want from your art and what success means to you.

Cole