Category: Articles

April 23, 2013

Cole Thompson shares some of his latest long-exposure images from recent trips

John Holland Memorial – Convict Lake, California

“I was in the Sierras to attend the memorial of an old friend and mentor when I created this image.

“John was on my mind as I spent several days reminiscing about our times together and missing him. He loved the Sierras and this is where he wanted his earthly ashes to spend eternity. I loved him and wanted to create an image to honor him and to remind me of him for the rest of my life. This is that image.

“When I create an image, I do not plan it, but rather ‘see’ it in my mind through my vision, and from there my challenge is to recreate that vision on paper. I envisioned this scene as very dark with movement in the skies.

“There are certain things I cannot control when creating an image, and clouds are one of them. I took a number of exposures here because the clouds just didn’t look right at exposures of 30 and 60 seconds. Because the clouds were moving so slowly, I needed a 4-minute exposure to create the feel I wanted. And to obtain such a long exposure in bright sunlight, I used a Vari-ND and ten stops of fixed ND filters.

“While creating this image, two girls played in the water in front of the rocks. But because the exposure was so long, their appearance never registered and it was as though they were never there.

Monolith No. 52 – Bandon, Oregon

“Each autumn I photograph the ‘Monoliths’ at Bandon Beach on the Oregon coast. I’ve been working on this series for several years now and have photographed these Monoliths in every season, weather, light, angle and time of day, and yet I always come home with something new.

“That’s the beauty of the creative process, there is always something new, even at a location I’ve photographed many times. There are so many variables, and I never know how one will change and trigger a new vision of a familiar subject.

“I used a 30-second exposure to highlight and isolate this Monolith, and it also simplified the image by smoothing out the details in the water and sky. In this image the effect of the long exposure is very subtle. In the majority of the situations I encounter, a 30-second exposure is sufficient to provide the look I’m after.

“Sometimes the effect of the long exposure is not even noticeable as in this image. A fast exposure captured the ripples in the water and I found this distracting. I fixed this by using an 8-second exposure which smoothed out the water and simplified the image.

“The photographer does not always need to create an obvious long exposure look in order to improve and strengthen the image.

Pigeon Point Light House – California Coast

“When I came across this light house I almost dismissed it because it was such a very traditional black and white scene that had probably been photographed by every photographer who had ever passed this way. But it was such a beautiful scene that I wanted to try to put my touch on it and make it just a little unique.

“The wispy clouds in the sky were what caught my attention. I envisioned the final image with the water and sky tied together by a similar look. I tried dozens of different exposures from a few seconds to several minutes, with each exposure creating a very different look. Because the water and sky were constantly changing, I could sometimes get the sky just right but not the water, and vise versa.

“Finally I got the look I was after with this 100-second exposure.

Dunes of Nude No. 58 – Death Valley, CA

“This image is from my series ‘The Dunes of Nude’ which is my interpretation of sand dunes. Normally I get very close to the dunes and photograph them in a very intimate and almost abstract way, but in this image I took a much wider view. Like the Pigeon Point image above, I wanted to tie the sky to the foreground by making the clouds look like sand dunes in the sky.

Ancient Stones No. 12 – Joshua Tree, California

“This new addition to my ‘Ancient Stones’ portfolio was created in Joshua Tree. I want to emphasize the permanence of these stones and the movement in the clouds is a subtle way of doing that.

“A key to my work is being able to move quickly; to be able to compose quickly and to adjust my exposures quickly. If I cannot do that, conditions change and I miss the shot.

“That is the primary advantage of the Vari-ND filter over fixed filters. I can open up the filter to quickly change my composition and can quickly adjust from a 30-second to a 120-second exposure. The Vari-ND is one of my most important tools.”

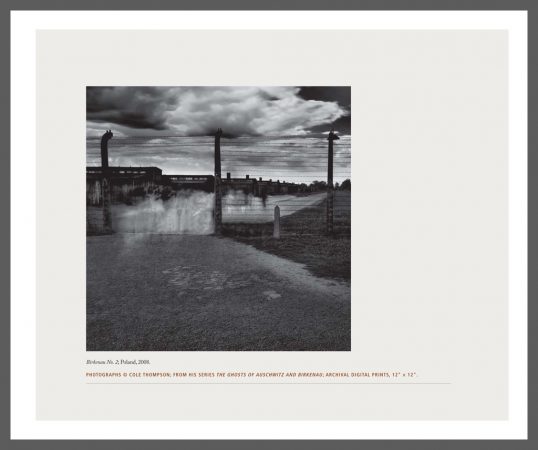

In May, Cole will be presenting an exhibition of his ‘The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau‘ portfolio in Split, Croatia at FotoKlub Split. You can check his website, blog, and social media for more news and information.

April 2, 2013

(click here to go to the Original Article)

(Puche, 2013b)

The landscape of nature is like the human figure – it is a subject with endless possibilities for expression. Photographs of the environment can be appreciated simply for their depiction of beauty; they can reveal truths about our relationship to nature and our understanding of wilderness; they can teach us the basic elements of design. Landscape photography can reveal as much about the photographer as it does about the meaning of the landscape, because their photographic treatment reveals their artistic vision.

In this essay, we will look at the design and meaning of an individual work from each of three landscape photographers, Fernando Puche, Jay Patel, and Cole Thompson who represent various directions in landscape photography.

Fernando Puche (http://www.fernandopuche.net/) is a Spanish photographer with many years of experience and significant public recognition for his work. He has published several books, including, Photography and nature: Beyond the light (2003), The Inner Landscape (2005), An Imaginary Journey (2007), Chronicles of a skeptical photographer (2009),How photographer Fernando Puche works (2009) and Diary of an amateur photographer (2012).

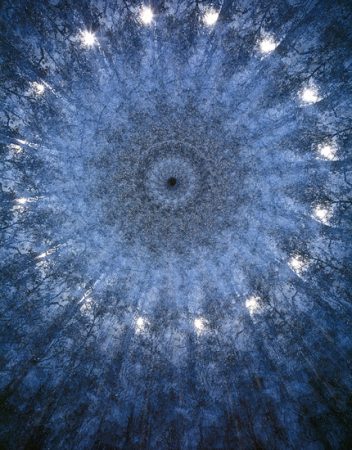

The work I’ve selected to look at for this essay translates as “Multiplied Forest #6? and is from a series of the same name where the photographer layers natural elements over each other to create an near-abstract image using multiple-exposure. He says of his this series:

This portfolio is an attempt to go beyond all those images which show the natural world as something beautiful and spectacular. A way to go beyond that “taste” of reality that exude my former images. The multiple exposures technique let me to create images standing between reality and fiction, so the resulting work is more abstract and much less “documentary”. (Puche, 2013c)

Many of the images take on a symmetrical composition, as it appears that he rotates the film (or sensor) holder in the 4 x 5 camera as each exposure is made. It seems clear that these works are still about what is “beautiful and spectacular” just as much as the photographer’s previous work, which consisted of images of nature a la Eliot Porter (an early pioneer of color landscape photography) – very tightly composed and subtly colored – that depict sublime nature.

To depart briefly from the main topic to discuss what it means to make photographs of the sublime in nature, we can simply consider what other approaches there are. Other photographers make images that are about other aspects of nature beside the sublime: how we view nature, how we treat it, how we try to replicate it.

Japan. Miyasaki. The Artificial beach inside the Ocean Dome. 1996 © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Japan. Miyasaki. The Artificial beach inside the Ocean Dome. 1996 © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos(Parr, 1996)

It is the case that these new images are no longer about the sublime, because the photographer is paying less attention to the appearance of the elements in their natural state and instead using their form to create other textures, colors and shapes. In other words, a photographer interested in depicting a romantic view of nature will compose the image to only include those elements consistent with grandeur and rationale order, often excluding details to create the illusion of nature untouched by humans. Puche’s images are still very much about beauty, but in a different way: they are carefully chosen elements that are delicately layered over each other to build intricate patterns and nuanced color.

Puche’s stated purpose is to use natural elements to create fictions of nature, but these images are as much fictions as the photographs in his portfolio which do not involve any obvious manipulation. In this older images, which Puche refers to as “documentary” he was also creating a fiction of nature, it was just a different story. For example, in the image below, Puche has created a fiction about water flowing down a cascading waterfall. It is an aesthetically pleasing image using the technique of long exposure to give the water a misty smooth experience, which contrasts with the sharp edges of the shale and the texture of the leaves.

White National Forest, New Hampshire, by Fernando Puche

White National Forest, New Hampshire, by Fernando Puche(Puche, 2013)

Water does not look like this in nature to the human eye – the image is a fiction about nature. This view of running water exists only because the photographer used a long exposure. It is as realistic a view of nature as water frozen in motion at a very high shutter speed – our eyes cannot perceive either end of the spectrum of motion. A photographer chooses this technique for a variety of reasons: it looks magical, soft and smooth; it creates an unexpected and pleasing texture; it cleans up any imperfections in the water; and it creates a spatial layer in the image. The story it tells is of the place; it is a story of the sound of the water as it rolls over the shale, the transparency of the water as it bends over the edge of the stone and the idea of an unending flow of water passing down the mountain into the valley.

When we talk about creating a fiction of nature, it is not to be critical, rather, is is simply important to acknowledge that the act of making a photograph is a complete fiction – the photographer starts changing reality the minute they frame the image, choose an exposure, select a shutter and aperture combination, among many other choices.

Are Puche’s new images between reality and fiction? This is not really their main topic. In other words, the technique the photographer uses extracts shapes and textures from the reality of nature and combines them in a manner not visible in nature, but this is exactly the same as use of long exposure.

My interpretation of these photographs is that they are still very much about place, but the photographer is acting more vigorously to tell that story. As we look at the image of the tree tops layered over each other in “Multipled Forests # 6?, it conveys the feeling of expansiveness, layered space, and even the dizziness resulting from tilting your head back and looking at the tops of the trees. The layering of pattern that Puche builds his images with amplify the design of nature and convey the quality of the space and place.

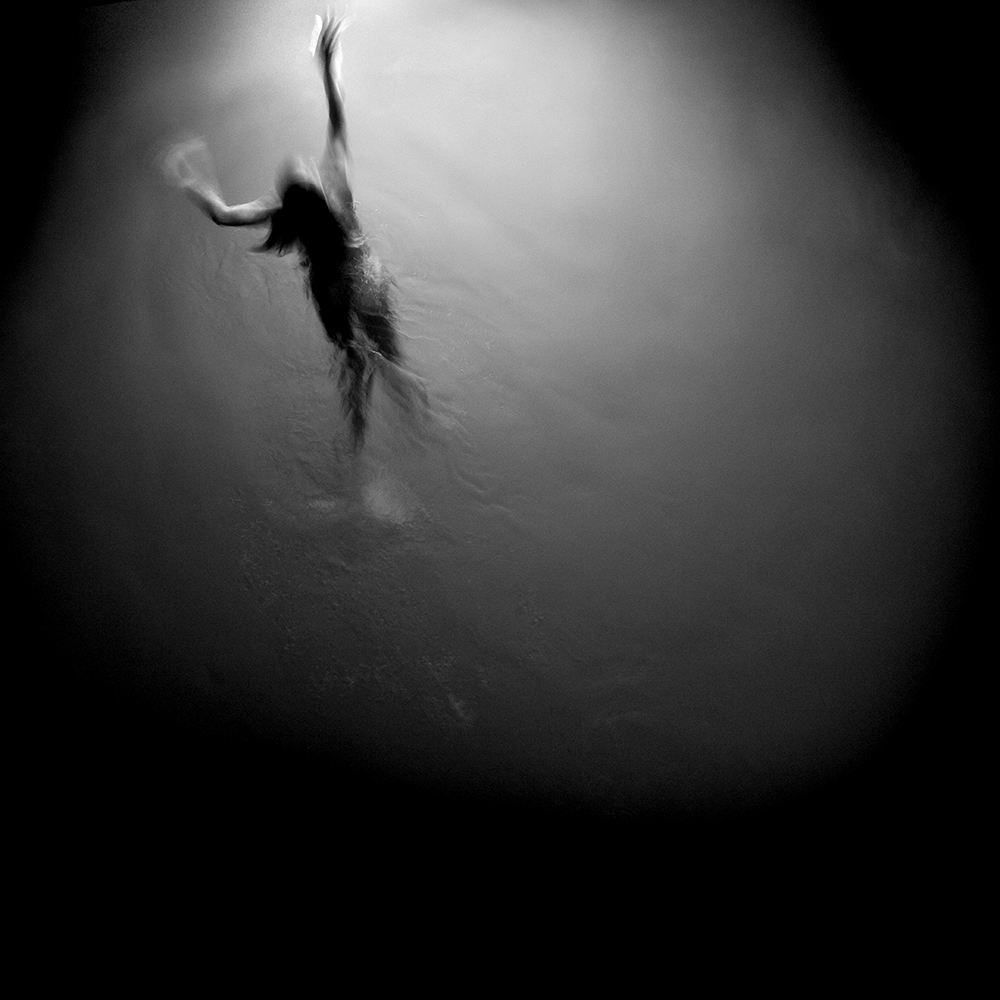

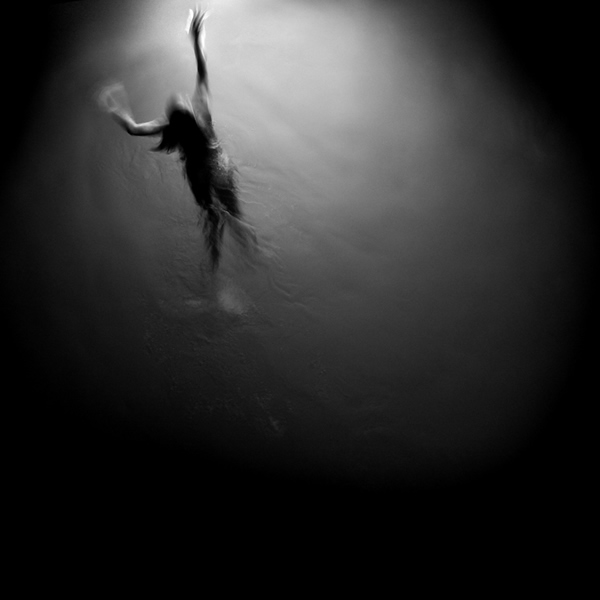

Harbinger No. 1 by Cole Thompson

(Thompson, 2008)

Cole Thompson (https://colethompsonphotography.com/Portfolios.htm) is a versatile photographer with interests that span from documentary photography, portraiture, and landscape, but for the purpose of this essay we will focus on the Harbinger series. Many of his landscapes images are not about the landscape at all, rather, they are analogies of emotional or spiritual states. This is actually quite different than Patel and Puche, who both keep their work referenced to the subject itself. Thompson introduces us to his series using the definition of harbinger:

Harbinger: \?här-b?n-j?r\ noun

1. one that goes ahead and makes known the approach of another; herald.

2. anything that foreshadows a future event; omen; sign.

(Thompson, 2008)

Although this textual context is important to help the viewer have a point of departure to interpret the images, he does an effective job of getting this across in the image itself. Lets look at how he goes about this.

Thompson’s compositions have a minimalist style in this series – they only include the essential elements to make the visual statement. He uses framing and exposure to do so. Many of the images are low key, in other words the middle tones are darkened considerably, the shadows are exposed to be solid black, and the highlights shown are only those at the high end of the spectrum. It is likely that he uses filters or digital color conversion to achieve this effect. The result is an image in which the sky is surrealistically dark, the landscape is reduced to limited detail and basic forms, while the light tones of the cloud are dramatically emphasized. The cloud as “harbinger” appears either as a menacing element or as an omen of good on the horizon, although centering the cloud in the frame leads to a more optimistic possibility. Cole Thompson’s photographs build expectation; the image is frozen, but a mysterious event is implied. His images are a visual representation of a foreshadowing.

The idea that photographs of elements in nature could refer to other possibilities was popularized by Alfred Stieglitz with his “Equivalents” series in 1926, so Thompson is building on an a tradition in photography as valid and as significant as landscape photography that is completely self-referential

(Patel, 2012a)

Jay Patel (http://www.jaypatelphotography.com/) is a meticulous landscape photographer who uses the latest developments in HDR techniques to present highly detailed, richly colored, and carefully crafted compositions of nature. His website describes the purpose of his work:

His photographs try to capture both the physical and emotional nature of light. “Light in nature takes on astonishingly diverse shapes, forms and colors that allow us to interact with the world around us…. He is well aware, however, that his photographs can convey only so much of the wonder as it is beyond his abilities to replicate the awe and magnificence of the natural world. (Patel, 2012b)

Jay Patel uses the highly controlled digital exposure and layering techniques he has developed to fill his shadows, midtones, and highlights with even more tonal detail than our eyes can perceive. His application of technique is directly related to his objective of exploring the way light describes elements of the landscape.

Although Patel describes his purpose as “replicating the awe and magnificence of the natural world” (it would be hard to describe the sublime in nature any more clearly), I see Jay Patel’s work as being about abstraction even more than the work of Puche. Jay Patel’s work is unabashedly about the way he sees nature – about the beauty that he sees… and he has developed the visual and technical skills to really communicate this very effectively. The reason he can make such compelling images of nature is because he is able to abstract the essential design elements of the scene. He communicates his vision and feeling for the place by deconstructing the space into essential forms and carefully arranging his composition to build an image that communicates his vision.

For example, in “Elowah Falls”, Patel uses the same long exposure technique as Puche in White National Mountain Forest” to transform the waterfall into a misty stream of flowing white energy that creates a dominant vertical presence in the frame positioned right at the 2/3rds mark of a horizontal grid of the frame. The very diffuse light that describes the rest of the valley, which is dominated by large massive shapes in the form of moss covered boulders, creates soft undulations of green hues. The large shapes of the stones are broken up by the diagonals of fallen tree limbs which add more visual movement to the frame without disrupting the dominance of the waterfall. In order for Patel to compose this frame, he must look at it abstractly – he must move conceptually past the moment and the physical three-dimensional reality and see it as form being shaped by light.

You can read more about this particular image and how he actually cropped it from his original exposure here. His crop removed an appearance of the mountain stream from the bottom of the frame, which improved the composition by providing a stronger visual foundation to the image and gave the waterfall much more preeminence in the image.

If you were thinking that a good landscape photographer brings you a document of the landscape they photographed, think again, because what Puche and Patel reveal to us is that good landscape photographers present us is with their coherent and striking vision of how they saw and experienced nature.

So how do we compare the three photographers? Jay Patel and Fernando Puche’s work depart from a similar premise – to share their vision of place – they speak to use about their subject, telling us stories of the design of nature and light. Cole Thompson uses the landscape to express a concept that is not related to the landscape at all, but rather is related to the human condition and our expectations in life. All three photographers create work that merits reflection and consideration.

References

Parr, Martin. (1996). Japan. Miyazki. The artifiical beach inside the Ocean Dome. Retrieved 3/30, 2013, fromhttp://mediastore2.magnumphotos.com/CoreXDoc/MAG/Media/Home1/e/8/7/c/LON14581.jpg

Patel, Jay. (2012)a. Elowah Falls, Columbia River George, Oregon. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, from http://www.jaypatelphotography.com/photography/quick-tips/quick-tips-cropping

Patel, Jay. (2012)b. About. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, fromhttp://www.jaypatelphotography.com/jay

Puche, Fernando. (2013)a. White Mountains National Forest. The Charm of Fall. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, from http://www.fernandopuche.net/Files/portfolio0201.html

Puche, Fernando. (2013)b. Multiplied Forest #6. The Multiplied Forest. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, from http://www.fernandopuche.net/Files/portfolio0909.html

Puche, Fernando. (2013)c. Artist Statement. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, from http://www.fernandopuche.net/artiststatement.html

Thompson, Cole. (2008)b. Harbinger 1. Harbinger. Retrieved 3/29, 2013, fromhttps://colethompsonphotography.com/HarbingerImages.htm

February 23, 2013

http://nlwirth.com/blog/cole-thompson-interview

Typically, I begin with an obvious question about what initially inspired you to pursue photography. I’ll ask about that later, but I’d like to begin with asking you about your overall understanding of vision and why you think it is so important.

Cole: Why is vision so important? Because it’s what makes our work unique. It’s the one ingredient that can transform a “captured photograph” into a “created image.” It’s more important than technique or an exotic location; it’s more important than a great camera or an expensive lens. With vision, you can take the simplest scene and create a masterpiece. Without vision, you can have all of the best equipment and techniques, and all you’ll end up with is a technically perfect “photograph.”

My rule of thirds states that a great image is comprised of 1/3 vision, 1/3 the shot and 1/3 processing. However, vision is the most important of these because that is what should drive both the shot and the processing. Vision transforms what we see with our physical eyes into what we see with our mind’s eye.

Sometimes we focus on the other things– equipment, technique and gadgets– because developing one’s vision is hard. Understanding and achieving vision is a nebulous concept, and it doesn’t come very easy for many of us. I used to think that I could compensate for my lack of creative ability by becoming extremely good at the technical. I studied the works of other photographers and mimicked them– specificallyAdams and Weston– in an attempt to be as good as they were. However, in the end, all I became was a great imitator. I had focused on everything except that which would make my work unique! Vision.

Nathan: What, then, is your overall vision for your work? Is it a single thing– or, perhaps, many, ever changing things?

Cole: I hope semantics and words do not get in the way of my trying to explain vision. But, for me, vision is not a thing but an understanding. My vision was always there; I didn’t create it, and I didn’t develop it. I simply discovered it and have learned to use it. But to fully use it, I must put out of my mind all stumbling blocks such as pride, envy, competition, insecurity and seeking recognition. These are barriers to vision and they impede the creative process.

I know that some could argue that there is nothing wrong with wanting recognition, or that competition is good, or that envy can motivate you to do better. I understand those arguments and for many things in life that might be true, but I don’t believe it’s true for the creative process. Anything that shifts your focus away from your vision and creative process is a distraction. If you are shooting to become famous, to win competitions or to get praise … you will not do your best work. It is only by learning to ignore those distractions and focusing completely on your creation that you can excel.

But let me also be clear that once you’ve created honest work through vision and produced something that you love, then there is nothing wrong with exhibiting, winning competitions, receiving recognition and praise for your work. Those things are the natural outcomes from following your vision, but if you only create for those goals then your work will lack conviction and power. That is my honest opinion.

I sometimes do talk about “developing” vision, but the more I live with my vision and think about it, the more I believe we actually don’t develop it. I believe we just come to understand it better and learn to follow it more. As we have new experiences in life, our vision naturally changes and so does our work. I just had someone express the thought that vision sounded limiting, and that once you find your vision your work will forever look the same. I disagree with that; our vision has nothing to do with the subjects we photograph, our style, or the techniques we use. Discovering one’s vision does not mean one’s work is doomed to be forever the same. In fact, I think that the opposite is true, that as we continue to understand our vision better and clear our minds of those distractions, our work will be ever changing. This has been my experience.

Nathan: I find your response very intriguing because it addresses, in a sense, the mystery of where creativity even comes from. It sounds like you advocate getting out of the way of such questions– and the whole concern of how to find it or cultivate it– and just doing it, just creating the work, the rest inevitably falling into place. I think many would wonder, however, if this can really only be done after you have managed to harness the basic understandings necessary for working with the mechanisms, the workings of the camera. In retrospect, do you think you arrived at your conclusions about what vision means as a result of much trial and error– and, perhaps, even pursuing recognition and acceptance and praise too early (only to find that it did not really justify and/or satisfy what you were really interested in ultimately doing with your work because it was, as you suggest above, blocking your creative impulses)?

Cole: I think you’re right. I don’t care as much about the “why” behind things. I just want to create. Talking about it and analyzing it is not my style, and, besides, I’m not certain that knowing those answers will make me a better artist. In my opinion, doing trumps analyzing.

There is no doubt that a certain technical proficiency is needed to be a photographic artist. Without those skills, we would be unable to transform our vision into an image. We could see the image in our own minds, but we would never translate it into something that others could see.

However, I think that the pendulum has swung too far and for too long in emphasizing the role of technical skills in photography. Yes … theyare important, even critically important, but couldn’t the same be said for vision? Is one really more important than the other and do the technical skills truly need to come first? I frequently hear people say that that you cannot really excel in the creative until you have developed a certain technical proficiency, but I believe that kind of thinking is backwards. As I look back on my photographic life, I now see that my emphasis on the technical was a substitute for working on the creative and that focus actually retarded my creative growth. If I could do it all over again, I’d focus on the creative right from the start and learn the technical only as my images required it.

The technical, in my opinion, is far easier to learn than the creative. I believe that’s one of the reasons we photographers focus so much on equipment and technical processes; we do it because we know how to do that. I think we are a bit uncertain how to find our vision, so we take refuge in what we can grasp: the technical. That’s what I did. Because I doubted my creative abilities, I compensated by becoming an expert technician. And that did carry me for a while, but, in the end, I was just another photographer creating technically perfect images that lacked soul. Neglected, my creative side atrophied and that further reinforced my belief that I had no creative abilities.

So bottom line, I’d encourage people to focus much more on the creative and much less on the technical. And I’d pursue the technical only in response to a creative need.

Nathan: I think one of the most talked about and, perhaps, most misunderstood question on the minds of many artists, including, of course, photographers, is: what exactly is fine art? Typically, many seem to respond that the answer is inextricably bound to the taste of the viewer, the goals of the creator, and inevitably, the opinion of the critic and the curator. Is fine art even something concrete, palatable– or even real– or is it more of a marketing tool or, perhaps, even a way for critics, sellers, and artists to label the work? I am curious about what your response to these questions might be– especially taking into consideration your understanding of vision.

Cole: I am not interested in defining “fine art,” and I don’t care how anyone else defines it either. What some expert, art critic, gallery owner, or curator calls fine art has no impact on me or what I do. They are merely one of a million opinions floating around in the ionosphere. When I look at an image, I simply know if I like it or if I don’t. Does anything else matter? Do I like an image less because someone tells me that it’s not fine art? (I’ve had that happen before).

For me, creating is doing what I want and not caring what others think. It is pursuing my own vision regardless of what others think. It’s about being so absorbed in the creative process that I’m not even aware of what others think! That moment when you realize that it’s irrelevant what others think is a wonderfully liberating feeling.

At the end of the day there is only you, your creations, and your opinion of your work. In the end, nothing else matters.

So why do some feel the need to define fine art? I’m sure one reason is simply to be able to classify work into categories so that we can communicate; for example, when I say that I create “fine art photography,” we all generally know what I’m talking about. So to some degree, we use these terms simply to be able to communicate, but I don’t spend much time worrying about a precise or universally accepted definition. I don’t have the time nor the patience.

Just so someone doesn’t think me a hypocrite, I do use the term “fine art” in my marketing. For example, I have targeted the Google search phrase “B&W Fine Art Photography” (search me, I’m number 1 out of 2,650,000 search results). So even though I have no use for defining “fine art,” I do recognize that it has a generally accepted meaning and that people use it to search for a certain type of image. I do use that to my advantage.

Nathan: Looking through your various projects, I see quite a few directions that you have followed— from “The Lone Man” series to the “Monoliths” series to “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” series and others— do you think there is any particular thread or overall theme that ties these together or are you moving from series to series individually?

Cole: There is no intentional connection between my portfolios and there is very little connection in terms of subject matter, but my work is all tied together by my vision, and that sometimes can produce a similar look between bodies of work– even though it is not intentional.

Many times over the years, people have advised me to pick one subject, focus on that and become known for that. However, that advice never sat right with me and I’ve always ignored it. I’ve been very fortunate to photograph a wide variety of subjects, and I’ve loved each project that I work on. I’d be bored if I was restricted to landscapes or any other individual subject! I believe that great work comes from passion, and pigeonholing yourself is not likely to produce much, if any, passion.

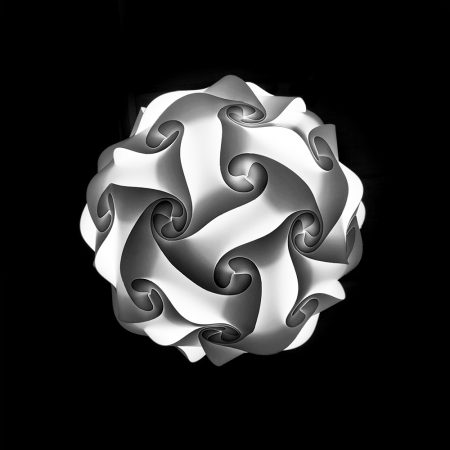

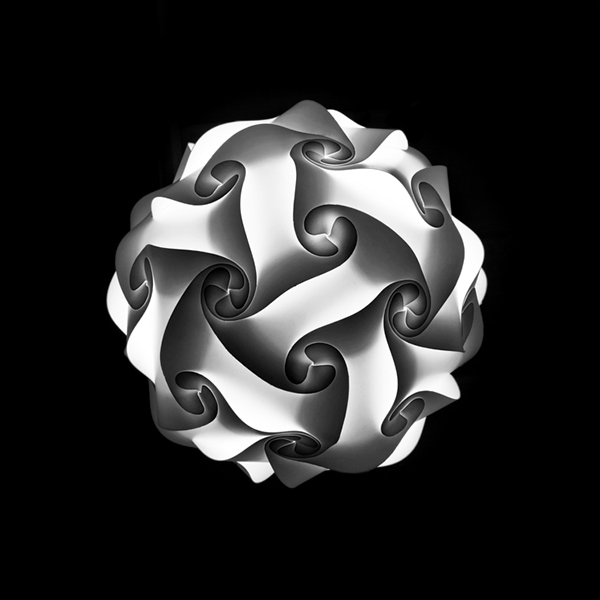

My roots are in traditional landscape photography, so you will see that influence in my portfolios. For example, my Death Valley portfolio, which appeared in the Sept/Oct 2012 issue ofLensWork, hearkens back to my roots much more than my other recent work. Then take a look at my “Ceiling Lamps” series and you’ll see a completely different subject and approach. Move onto my “Monoliths” portfolio and I’ve again changed subject, look, and style. Then there is my architectural series, “The Fountainhead,” and, well, you get the idea. My variety seems to fly in the face of the conventional wisdom to pick one subject and become known for that, but I don’t agree with that conventional wisdom.

People write to me all the time, almost sorrowful because their work is so varied. They seem to feel that this indicates a lack of concentration or discipline, which I don’t think is necessarily so. Following your vision doesn’t mean that your work focuses on the same subject or is similar looking. Vision should never be confused with a “look” or “style,” but, rather, it should be understood as an approach to creating images. While my portfolios have no common subject or theme, I do believe there is a common thread connecting them, and that thread is the way Isee and treat those subjects. I reject the concept that you must focus on one thing or develop a “look” to become successful; I would, instead, propose that the key to success is finding and following your vision.

Sometimes my work is not a “critical” success, but that is not how I measure success. I measure it by how I feel about the project and not by how others react to it. Take my portfolio “Ukrainians, With Eyes Shut,” a series of street portraits in which I asked the subjects to shut their eyes: this portfolio generated very little critical interest, but I love it, nonetheless. And, conversely, my series “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” was extremely well received, but that does not make me feel any differently about this body of work or make me go out and duplicate it (which people have advised me to do). There is this great quote that I’ve modified to sum up how I feel: what anyone else thinks about your work is none of your business.

I think my work is so varied because I don’t study other people’s work, so I’m very unaware what others are doing. This means I’m less likely to say “Why bother photographing Auschwitz? It’s been done to death and I could never do better than so-and-so, so why try?” This kind of ignorance is bliss because it allows me to photograph something without being intimidated or influenced by others work.

Nathan: I have to talk to you about your photography celibacy, your decision to avoid looking at what others do with their photography so that you are not indirectly influenced by it or discouraged from pursuing a theme or subject matter that interests you because someone else has done it. How far do you take this? I know, from previous interviews that you have given that you have great admiration for Michael Kenna and Alexy Titarenko (two of my most favorite photographers). Do you still check in from time to time to enjoy their latest work? I’ll have to confess and say that while I most certainly understand your reasoning behind this, I personally could not sacrifice the pleasure of witnessing the ongoing “conversation” and “evolution” that has been happening since the beginning of photography. In other words, for me, a significant part of my enjoyment of photography is the work of others. I can easily guess that your photography celibacy is often met with a challenge from other photographers. I’d love to hear more about your thoughts on this.

Cole: I learned photography by reading and by studying the work of the great masters. As a boy, I spent hours a day looking at images, analyzing them, and trying to decide what I loved about them and why. It was such a huge part of my life that it might seem that photographic celibacy would be a difficult thing for me to undertake.

So why take the “vow of celibacy?” Well, because at some point, I transitioned from photographer to artist and my desire to uniquely create became the most important thing in my life, even more important than enjoying great photography. It’s really not a sacrifice for me because I’m so focused on my creative process that I don’t miss it.

Do I peek at Kenna’s or Titarenko’s work from time to time? No. The only work I look at now is the occasional friend’s images.

Why do I continue this practice after almost five years? Let me illustrate: not long ago I saw an image of three telephone poles entitled “Three Crosses” by Brian Kosoff. The image just floored me and I purchased it. But something else occurred; I immediately found myself thinking “where can I find telephone poles like that?” I had to consciously stop myself and remind myself of my goal! Perhaps it’s just me, but when I see a great image my mind immediately starts thinking about how I can imitate the shot or recreate the look. So now I just avoid that altogether.

There are many like you, who understand why I do this but you choose a different path, and I respect that. And there are a few who argue adamantly against my practice because they generally feel that art builds upon that which has come before, and so to progress you must be aware of what has come before.

Another variation of that argument is that you must study great art to be able to create great art. However, I just don’t buy the argument. How can filling your mind with other’s images help you to be more creative or unique? It has the exact opposite effect on me! Original thinking is hard to do, and while I have not completely achieved that yet, I’m determined to try.

I think the best defense I’ve heard for Photographic Celibacy is that it’s a useful tool at a certain point in a person’s creative development. And once that tool has served its purpose, you move on and find another. Certainly I don’t argue that I’ll be celibate for the rest of my life, but for now I find the practice useful in helping me to see more uniquely so that I can further develop my vision.

There is something else that I have found equally important in developing my vision, and that’s learning to not care what others think of my work. To create for oneself and not for the praise of others can bring great power and conviction to your work. I’m not saying that I don’t enjoy exhibiting and being published. I really do, but that’s no longer the reason why I create. That’s now an extra benefit of creating.

Edward Weston has always been a role model for me in this area. Here is my favorite Weston story as told by Ansel Adams:

“After dinner, Albert (Bender) asked Edward to show his prints. They were the first work of such serious quality I had ever seen, but surprisingly I did not immediately understand or even like them; I thought them hard and mannered. Edward never gave the impression that he expected anyone to like his work. His prints were what they were. He gave no explanations; in creating them his obligation to the viewer was completed.”

It is very hard to put out of your mind what others will think of your work, but it really is quite liberating. Ironically I’ve also found that, in pleasing myself, my work has become more pleasing to others.

Nathan: Do you think it is necessary for an artist to always remain fresh, unique, and on the cutting edge (whatever that actually even means)? For example, some might say that choosing to paint in a similar style to (or be influenced by) the great Dutch Masters– or the wonderful Hudson River School painters of sublime landscapes– would not be following the mandate that art must always progress, always change, always seek to say something new. I strongly feel that, by definition of the very act of the individual creating something in his or her own voice, that someone who does work in a style of the past– or any similar subject matter already covered by others– is still creating something unique and fresh because, by definition, it cannot be the same as the work that inspired it (the work being inextricably bound to the vision of its creator).

Cole: I’ll be honest Nathan: I’ve never studied art, so I cannot speak intelligently or with any perspective other than my own. I work hard to not think of my work in relation to what others are doing. I do not compare it in order to judge whether it is new, fresh, or unique. I do not care if it is cutting edge in someone else’s opinion; that type of thinking is not productive and would drive me crazy. I am completely serious when I tell you that I could care less if the most renowned art critic declared my work good or bad; it makes no difference to me.

But I do care if my work is new compared to what I have been doing, and I do care if it’s unique compared to my past work, and I do care if I think the image is good. This is all that matters to me.

Now it’s very hard to be objective about one’s own work and to answer the question “is it good?” I generally find that I love 100% of my images when I view them in the field, and about 50% of them when I look at them on the computer, about 10% of them when I do my first-pass processing, and about 1% of them when I look at them a couple of days later and finally about .25% of them when I view them a few weeks later. I do find that time helps give me a more objective and realistic perspective of my work.

Nathan: So let’s shift gears a bit and focus on some of your particular series/portfolios. I’d love to hear a little more about the vision or, if applicable, thinking behind some of your series. Specifically, “The Lone Man,” “Monoliths,” “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau,” “Dunes of Nude,” “Harbinger,” and “Ceiling Lamps.”

Cole: Each of my portfolios have come about spontaneously, suddenly, and without planning. When I see something, it excites me and I pursue it. How could life be any simpler or better than that? For a long time, I’ve kept a list of ideas, projects that I hope to pursue, but the truth is that I’ve never started a single one of them! I still keep the list, and I still think they’re good ideas, but I’ve never gotten excited enough to start one of them.

I typically complete my portfolios very quickly; many have been completed in days and weeks while some others have dragged on for a couple of years. This brings to mind a misconception that I had most of my life and one that I think others have: that a “serious” project will take years to complete. I always thought that the longer a project took, the better it must be. However, I no longer believe that. I don’t think there’s necessarily a correlation between how long a project takes and how good it is. For example, “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau”portfolio was completed in less than two hours.

So how long, then, should a project take? It takes as long as it takes.

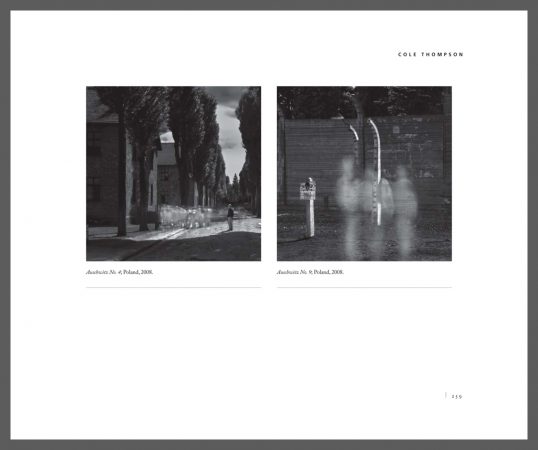

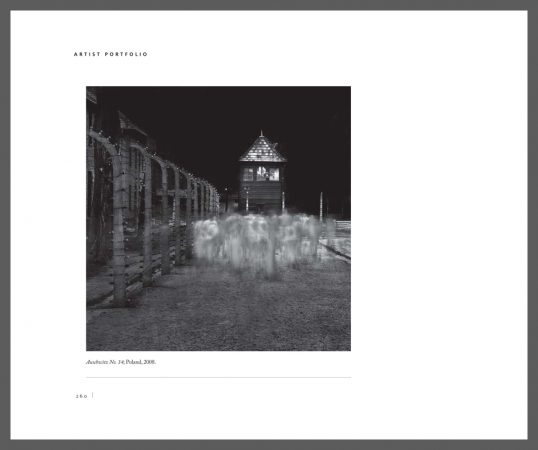

The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau: I was visiting my son, who was serving in the Peace Corps in Ukraine, and because I’m part Polish we decided to see Krakow. As we planned our activities, the family decided that they wanted to visit the concentration camps. I didn’t want to visit there because sad places make me sad, and while my wife loves a good cry, I tend to avoid discomfort! However the majority ruled and so off we went.

I had my equipment with me but decided not to photograph because I thought it might be sacrilegious. The tour started inside a building where we saw the documentation that was kept on each prisoner. We saw the infamous piles of shoes, glasses, hair and etc. We were about ten minutes into the tour when I started feeling claustrophobic and found it difficult to breathe. I signaled to the family that I was going outside to seek relief, and once outside I did feel a bit better. However, as I began to slowly walk, I looked down at my feet and began to wonder who had walked in these same footsteps before me, and what had been their fate? With each step I could not shake that question: who had walked here before me and now were dead? Then I wondered, perhaps metaphorically, if their spirits still walked here. And then the idea hit me; I must photograph the spirits of the dead who still walked the camps.

I had been working with long exposures for some time, so I was technically prepared. I had even used long exposures to create two recent images with people in them; “The Angel Gabriel” and “Two Kimonos,” so I understood a bit about creating ghosts. Armed with a little experience, an idea, and some inspiration, I started to work. I would use long exposures to photograph the other visitors at the camps and to turn them into ghosts. These unsuspecting tourists would stand in proxy for the spirits who had died there. Our tour bus was to leave in less than one hour and so I had to work quickly. I literally ran from shot to shot to complete these images.

One of the largest challenges was surreptitiously photographing the other tourists. When they saw my camera and tripod pointed at a scene, they politely held back and didn’t enter the area, which, ironically, was exactly what I wanted! Fortunately, I had encountered this challenge before when I was photographing in Tokyo, so I had developed some simple techniques to trick people. I’d turn my back, act like I was on the phone and when they wandered back in I would use a remote shutter release to take the picture.

To create the ghosts, I used 10 to 30 second exposures, and I had to take about ten shots to get a single one that worked, which consumed precious minutes as I raced against the clock and the departing bus. In the end, the bus tried to leave, but my family protested and my wife dragged me back to the bus. In that short time at Auschwitz, I was able to create twelve images and then another three at Birkenau, our next stop. These were the fifteen most important images in my photographic life thus far, and if I never create any better than this, I’ll be happy with this accomplishment. Often the shot was ruined if someone stopped moving during my long exposure because this person would then be recorded as a mortal instead of a ghost. In only one of my images do I purposely leave a “mortal” in the scene, and it’s been interesting to watch people interpret what that means. I have my own interpretation, but I enjoy hearing what others think– and I’ve heard a number of very interesting interpretations.

View the complete “The Ghosts of Auschwitz-Birkenau” series here.

The Lone Man: I was shooting long exposures at one of my favorite dive spots inLaguna Beach when a group of tide poolers walked into my scene. While I was waiting for them to leave, I decided to take a test shot so that I would have my exposure all set when they left. I recorded a 30 second exposure and when I looked at the image, I was surprised to see that one man had been perfectly recorded because he had stood perfectly still for the 30 seconds. As I looked at him, I noticed something very familiar about his stance; I had seen this attitude before. I realized that what I was seeing was the look that comes over people as they stand on the “edge of the world” and look out into the infinite expanse of ocean. They become still, contemplative, pensive, and thoughtful. And now that I had consciously noticed this, I began to see it in people everywhere which inspired me to create “The Lone Man” series. Here is my artist statement for the project:

Something unusual happens when a person stands on the edge of the world and stares outward. They become very still and you can almost see their thoughts as they ponder things much greater than self:

Where did I come from?

What is my purpose?

What does it all mean?

What is beyond the beyond?

Do I make a difference?

Is there more?

At that moment they are The Lone Man, alone with their questions and thoughts about life, the universe and beyond. People are affected by this time of meditation and often vow to make changes in their lives. But this moment is short lived as these weighty thoughts are replaced with more immediate concerns:

Should I eat at McDonalds or Burger King and should I try that new green milkshake?

View the complete “The Lone Man” series here.

Ceiling Lamps: I was standing in a hotel lobby in Akron, Ohio, waiting to check out, when I happened to look up. What I saw was a ceiling lamp that looked fantastic when viewed from directly below. It really didn’t look like a ceiling lamp to me at all!

I pushed all the lobby furniture out of the way and lay on my back to get a better perspective (which triggered offers of CPR, mouth-to-mouth, and calls to 911). This is the first ceiling lamp I created and from there it was all great fun to seek out these lamps and photograph them– all from the same perspective and style.

This was a fun, whimsical project, and I had a great time creating it. Once you become attuned to something, you begin to see it everywhere, and that’s what happened to me with this project. Someone once told me that I’d probably never win any critical acclaim for this project, and that’s okay. That’s not why I created it.

View the complete “Ceiling Lamps” series here.

Harbinger: “Harbinger” was a single spontaneous image that I never thought would lead to a portfolio. I was photographing some mud hills in Utah,where it was over 100 degrees and my teenage son was doing the “are you almost done?” routine (if you have children, you understand). A parent can only take so much of that, so I finished up, and, as we were heading back to the car, I saw this solitary cloud moving rapidly across the sky. In an instant, I could tell by its trajectory that this cloud was going to pass over those beautifully symmetrical mud hills that I had been photographing and I wanted that image! I ran back up the hill, set up my camera and tripod in mere seconds … and got off this one shot.

I named it “Harbinger” because it seemed to me that this one little cloud was a harbinger of things to come. I absolutely loved the image but instantly wrote it off as a “one hit wonder,” not because I didn’t think it was a good image, but because I thought the chances of finding another similar cloud and interesting scene were about zero. Surprisingly, I have found a few more, and I continue to work on this project as the opportunity arises. Now this is a project that will take me years and perhaps my lifetime to complete!

Recently, I added a new Harbinger image that has more than one cloud, but I feel it still fits the description of a Harbinger [note: it is the middle image below].

View the complete “Harbinger” series here.

View the complete “Harbinger” series here.

Monoliths: When I first saw the Monoliths on the Bandon, Oregon beaches, I knew that I would photograph them. I have always been fascinated with what I call “Monoliths.” First, as a boy I read “Aku Aku” by Thor Heyerdahl and learned about the giant stone statues of Easter Island, and, later, I saw 2001 A Space Odyssey and was fascinated by the monolith discovered on the moon. I don’t know why Monoliths fascinated me so much, but I have always thought of them as conscious beings who have always existed. I imagined them standing there motionless for eons, observing man as he scurried about full of self importance. That always made me smile.

Each September I return to Bandon to photograph, it’s my favorite stretch along the Oregon Coast. And each year I question whether I should return because it seems as though I’ve photographed the Monoliths in every conceivable light, from every angle and in every type of weather. But I do return and I do always find new images.

View the complete “Monoliths” series here.

Dunes of Nude: During my trips to Bandon, I always drive down the coast to this great wind surfing spot. It has this very narrow strip of sand dunes that are compressed against the highway, and because of the very small space, it creates this miniature sand dune system. It looks just like a regular dune system except that it’s in 1/4 scale with everything miniature and compacted. This spot has always attracted me, but I never really came away with images that I liked.

However, on my last trip there, as the sun set, something really spectacular occurred. The low sun transformed the dunes into something completely different and during every minute of that last low sun, the shadows and shapes of the dunes changed. You have to work furiously because the sun is so fleeting. I became enthralled with this last 20 minutes of sunlight and this work has developed into a new project entitled “The Dunes of Nude.”

Initially I portrayed the dunes with very light tones, an unusual choice for me, but one that I thought I’d try. But after living with the images for a while, I reworked them all to be dark and “contrasty.” Sand dunes have been photographed by thousands of people and in a thousand different ways, and so part of me says that I’m unlikely to portray them uniquely. But another part of me considers that a challenge and that makes it all great fun.

The Dunes of Nude is a work in progress.

View the complete “Dunes of Nudes” series here.

Nathan: I’d like to shift gears again. One of the many parts of your talk in Palo Alto that I enjoyed the most, was your various pieces of advice, your useful chunks of wisdom, to photographers. I especially loved your advice to photographers to keep it simple, both with the purchase of the latest and greatest equipment and with processing images. I’d love to hear more about your thoughts on these matters.

Cole: I am a recovering technophile. I’ve always loved gadgets and always needed to have the latest equipment before anyone else did. My home was gadget central, and I thought that being able to own all of this equipment somehow qualified me. However, all of this equipment and these programs required a lot of time to learn and to maintain, so much so that I had less time for actual photography. It also led to the twisted belief that a great image was dependent upon my equipment. When I saw a photograph that I admired, I would ask the photographer about the camera, the lens and settings. What was I thinking? That if I knew their settings I could create the image myself?

This attitude continued until I started discovering my vision, and, as a part of that journey, I made the commitment to stop focusing on the things that didn’t matter and to focus, instead, on the things that do. I started focusing on my vision, composition and the image. I reduced my equipment and processes to the minimum “needed” to do the job. The first benefit of this new thinking was simply that I had a simpler workflow with fewer things to go wrong.

Then something else started to happen, this philosophy of simplification started affecting my work. I noticed that I was focusing more on simple images, simple shapes, and simple concepts. Over time, I found my vision, and my work became simpler in its construction and it improved.

I am not against technology or equipment or processes; in fact, I’ll adopt any tool or process that is needed to fulfill my vision. But all of those “things” are merely tools that are servants to my vision. They are not the masters.

Nathan: What equipment (camera, lenses, and filters) and software do you use?

Cole: I use the following:

- Canon full frame cameras with a 16-35, 24-105 and 100-400 lens.

- Tripod and remote shutter release.

- A polarizer, a Singh-Ray Vari-ND filter and an assortment of fixed ND filters.

- A HoodLoupe by HoodMan

- Photoshop and typically six tools [note: see Cole’s answer to the question below for what those six tools are].

- Wacom Tablet

- Epson 7900 printer using the supplied Advanced Black and White mode

Nathan: I’d love to hear about your basic (or not so basic) approach to processing. Do you know, when in the field, how you are going to later process an image or is this discovered during the actual processing (or, perhaps, a little of both)?

Cole: My belief is that the image begins with your vision. Most of the time I know exactly how I want the final image to look and I can “see it” in my mind’s eye. I’ve become comfortable enough with my Photoshop capabilities to know that if I visualize it, I can usually make it happen. And if I don’t have the skills to make it happen, then I’ll research and learn until I have found a way to translate that vision into my image.

You do not need a lot of Photoshop knowledge to be able to create with vision; in fact, I know very little about Photoshop, but I know enough. I typically use only six tools inPhotoshop because I’ve found that I don’t need more than that. I believe that many of the “extras” that people use just add another layer of cost and complexity to the process with very little improvement in the image.

Here’s an overview of the six tools that I use:

- RAW Converter – I use Photoshop’s RAW converter to set my image to a 16 bit, 360 ppi, 10X15 TIFF file.

- B&W Conversion tool – I like Photoshop’s b&w conversion tool and play with each color channel to see how it affects the different parts of my image.

- Levels – One of the most basic secrets to a great b&w image is to have a good black and white. I use Levels to set the initial black and white point and I use the histogram to judge this, never my eyes. Throughout my processing I keep my eye on that histogram to maintain a true black and white. Something else I do while in Levels is to adjust the midtones, which can radically change the look of my image and tends to set the direction I will take it.

- Dodging and Burning – This is where I do most of my processing and where I have the most fun! I feel most at home with dodging and burning because that’s how I did things in the darkroom. However the primary difference today is that I can take my time and exercise minute control over every part of the image. I use a Wacom tablet to dodge and burn because you CANNOT do a good job with a mouse.

- Contrast Adjustment – After I have the image looking great on screen, experience teaches me that it will print flat, and so I add some contrast. A monitor uses transmitted light and a print uses reflective light, so that means it will take a lot more work to get your print to look as snappy as it does on the monitor. Contrast helps.

- Clone Tool – I use the clone tool to spot my images. Cloning is so much better than in the old days when you had to spot every single print and your mouth tasted like Spottone all day!

I also like to mention what I don’t use: I do not use any plug-ins or b&w conversion programs. I do not use a monitor calibrator. I do not use curves or layers. I do not use special RIP’s or printer drivers. I do not use special inks and I am not on a lifelong search for “the perfect paper” (life is too short). I find that most of these “extras” only add a very small amount to the image, and that generally when an image misses the mark, none of those things would have made a difference anyway.

What would benefit most people’s work is to focus on vision, work on their composition skills and then hone the technical skills that are needed.

Nathan: I also love your advice about how one should not take advice and criticism from other photographers about how you should have or should not have made a particular choice when composing or processing an image.

Cole: People who give advice are generally well intentioned and oft times experienced. However their advice comes from their vision and their point of view, not yours which makes all the difference in the world. If I were to tell you how to process your images and you listened to my advice, then your images would begin to look like mine. That’s not right, they should look like your images that were created with your vision. Consequently I try very hard to not give advice to others about their images, how they should process them or how they should look.

Nor should you listen to the critics; art critics, professionals or others on photo sharing websites. Listen only to yourself and ignore the world. I remember the first image that I had created with my own vision, The Angel Gabriel. I showed it to my mentor at the time and she immediately said “Never center the image!” Something about her advice felt wrong, I had purposely centered it because that is how I had envisioned the image and how it felt. But, she was the expert and so I tried cropping it off center.

Seeing this image almost made me sick, this is not how I saw it through my Vision. This taught me to always follow my Vision, and to not to follow others advice (no matter how well-intentioned).

There is a saying that I try to live by: what others think of your images is none of your business. This requires a confidence in your vision and in your work, and when you have that confidence you’ll not need other’s advice.

One of my favorite books is The Fountainhead which is the story of Howard Roarke, an architect full of vision and self confidence. His friend Peter is a fellow architect who is insecure about his work and is constantly asking others what they think of it. At one point Peter comes to the Howard to ask his opinion about a building he has designed, here is Howard’s response:

“If you want my advice, Peter,” he said at last, “ you’ve made a mistake already. By asking me, by asking anyone. Never ask people, not about your work. Don’t you know what you want? How can you stand it, not to know?”

Now this vision and confidence does not come overnight, but it is my goal and I am constantly striving to reach that level of independence.

Nathan: Do you have any general advice for aspiring photographers?

Cole: My advice will be pretty predictable:

- Don’t listen to other’s advice (anyone see the irony here?)

- Define success for yourself before you go seeking it.

- Focus on your vision and do not imitate others.

- Understand the role of equipment and processes, they are subservient to vision and the simplest tools can produce incredible images!

- Be honest and sincere, these qualities have much more to do with being a good artist than most people understand.

Nathan: Are there any artistic influences outside of photography that have inspired your work– for example, painters, poets, writers, films, music, etc?

Cole: Yes, several.

- The Poem Invictus – My success is not dependent upon others; “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”

- The music of The Beatles – it reminds me to not to keep producing the same type of work simply because it was successful, in an attempt to remain successful. Experiment, grow, change, and shake it up!

- The novel The Fountainhead – It taught me to not care what others think, to follow my own vision, to define success for myself, to be independent.

- Edward Weston – I learned from Weston to not care what others think of my work, in creating the images my obligation to the viewer is complete.

- God – I believe we all have been given unique talents and that we should develop them. I have always believed that I was destined to be a photographer and artist.

Nathan: Do you listen to music when you process your photos? If yes, what do you listen to. And does music play a significant role in your creative process?

Cole: Yes I do listen to music while I work, I have splurged and installed a nice system in my office. As we write this I’m listening to the Alan Parsons Project. My library consists of 60?s and 70?s music, Jazz, Classical and Latin.

I’m not sure if listening to music while I process my work helps or not, but I do enjoy it!

Nathan:Any last thoughts or anything you would like to add?

Cole: I know that not everyone will agree with all of my ideas. Despite how I might come across, I am not advocating that this is the “right way” or that my approach is right for everyone. This is simply what I have learned and what I now believe. So I hope that nothing I’ve said has offended someone who believes or practices differently.

Who knows, in a few years I may look back to what I’ve said here and think “what a load of horse crap!”

Nathan: Now that we have talked about your vision, process and other thoughts about photography, I’d like to end with the beginning and the future: when did you first become involved with photography? What first inspired you? And do you have any specific direction you would like to take your work in the coming years? I’ll also take this moment to thank you for doing this, Cole. It’s been a pleasure to read your responses. I look forward to seeing where you take your work in the days, months and years to come.

Cole: You’ve always been so kind and supportive of me, Nathan, thank you. I enjoyed meeting you last year in Palo Alto. In this Internet age I’ll often “know” someone for years before I ever meet them! And thank you for asking me to talk with you about these things, I always enjoy expressing my thoughts because this process helps me refine my beliefs.

I discovered photography at age 14 and immediately knew that I was destined to be a photographer. I was out hiking with a friend in Rochester, NY when we came across an old ruin. My friend told me that the home had once been owned by George Eastman, the father of Kodak and in many ways the father of modern photography. This piqued my interest and so I checked out Eastman’s biography from the school library. I was fascinated by the story of photography and before I had finished the book, before I had taken a picture or watched a print come up in the darkroom, I knew that I would be a photographer. I felt destined.

I know that sounds silly and perhaps presumptuous, but it is honestly how I felt and have continued to feel throughout my life. This feeling of destiny started a 10 year intensive journey of personal study and self-education. I am self taught, I’ve never taken a photography class or workshop in my life. I literally spent every waking moment either reading and learning technical processes, working in the darkroom or studying the images of the great masters of photography. I was drawn to the work of Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Paul Strand, Wynn Bullock, Paul Caponigro, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham and others. I noticed that I was drawn to a particular type of image, dark images and contrasty images. When I’d see an image that struck me, I’d get this chill that would run down my spine. I wanted so badly to be able to create images like that and I worked hard to learn to do that.

Over the years my goals have changed and will probably continue to develop. Instead of wanting to be a photographer, I wanted to become an artist who used photography. Instead of documenting, I wanted to create. Instead of copying others, I wanted to find my own vision. Instead of being famous, I wanted to please myself.

What direction do I want to go in the future? I want to continue to try and see uniquely, to find joy in creating, and to combine my desire to see the world with my desire to create art

In so many ways I feel I am the luckiest person in the world.

Explore More of Cole’s Photography: website | blog | newsletter | emai

All images on this page– unless otherwise noted– are protected by copyright and may not be used for any purpose without Cole Thompson‘s permission.

The text of this interview is also protected by copyright and may not be used without the permission of Nathan Wirth or Cole Thompson.

December 20, 2012

December 18th 2012 by Andrew S Gibson

This article is part of a series of interviews with long exposure photographers to celebrate the release of my ebook Slow. You can keep track of the interviews by clicking on the Long Exposure Photography Interviews link under Categories in the right-hand sidebar.

Cole Thompson is a fine art photographer based in Colorado in the United States. As part of the interview I asked him how, in a world where it seems that many photographers are producing similar work, it is possible to create original photography? His answer is worth reading, as it brings up one of Cole’s most interesting concepts, ‘photographic celibacy’.

Interview

How would you describe your photographic vision? What kind of look do you try and create in your photos?

I cannot describe my vision because I believe vision is intangible and indescribable. I view vision as the sum total of my life experiences. It is what makes me see the world a bit differently than another, because my experiences have been different.

I do not try to create a look or pursue a certain style in my images, I simply follow my vision. If you pursue a look, style or technique without vision, then those things are mere gimmicks and your images will lack power and conviction. I have been creating images since 1968 and so my skills would allow me to pursue many different styles or looks, but I’m only interested following my vision.

What I’ve learned is that vision must always come first and then techniques and style must flow from it. I’ve also learned that I must only create images that I love, that’s where my passion is and where my best work will come from.

Name three photographers you like and why.

Edward Weston is my photographic hero, not because of his images (although I do love them) but because of his attitudes. In my opinion Weston was a true artist and not a photographer (I draw a distinction between the two). He was independent in thought and did not care what others thought of his work. He created for himself and he had no obligation to explain his work to others.

One of my favourite stories is told by Ansel Adams on his first meeting Weston:

“After dinner, Albert (Bender) asked Edward to show his prints. They were the first work of such serious quality I had ever seen, but surprisingly I did not immediately understand or even like them; I thought them hard and mannered. Edward never gave the impression that he expected anyone to like his work. His prints were what they were. He gave no explanations; in creating them his obligation to the viewer was completed.”

In so many ways Weston has been my mentor. I re-read his Day Books every year and often read them just before I go out to create new images. His independence and obligation to self has inspired me.

Wynn Bullock. As a 14 year old boy I taught myself photography and part of what I did was to sit for hours looking at the work of photographers. Wynn Bullock was one whose work I admired and it wasn’t until years later I realised how much he and I saw alike, with both of us gravitating towards dark and contrasty images.

Ansel Adams. For many years I dreamed of being the next Ansel Adams (like millions of other young photographers). And for years I tried to imitate his look and even specific images. But then something happened to me that changed my attitude and led me on my quest to find my own vision. I was at a portfolio review and a gallery owner quickly looked at my work, brusquely pushed it back towards me and said “It looks like you’re trying to copy Ansel Adams.” I proudly told him that I was because I loved his work! He then said something that really made me mad at the time, but later opened my eyes, he said:

“Ansel has already done Ansel and you’re not going to do him better. What can you create that demonstrates your vision?”

That was the beginning of the search for my vision. I still love Ansel Adam’s work, but I no longer want to be known as the “best Ansel Adams imitator in the world.” In fact, now if someone says to me “your work reminds me of Ansel Adams” I know that I have failed to distinguish myself with my own vision.

Long exposure photography – what’s the attraction and why do you do it?

The long exposure is not something I set out to pursue nor is it a marketing strategy I chose to become known as “the guy who uses long exposures.” But rather it’s the outcome from following my vision: it’s what I love, it’s how I feel and it’s how I see the world.

About 90% of my recent work was created using long exposures. I initially started off with water, then moved to clouds and now have been creating images of people with it as well. I suspect I’ll find other areas in which to use it as well.

Why black and white – what is the appeal for you?

That is a very difficult question to answer and perhaps my artist statement says it best:

I am often asked, “Why black and white?”

I think it’s because I grew up in a black-and-white world.

Television, movies and the news were all in black and white.

My childhood heroes were in black and white and even the nation was segregated into black and white.

Perhaps my images are an extension of the world in which I grew up.

I really don’t worry too much about the “why” behind things, I simply accept them as they are. I love black and white and always have. I’ve tried dabbling in colour and I’ve seen a few colour images that I’m drawn to, but in the end I really am just a black and white guy and I’m okay with that.

I can see from your portfolio that you are widely travelled, especially within the United States. How important is the contribution of travel to developing your portfolio from an artistic point of view? How has travel helped you develop as a person?

Travel is not critical for me in terms of subject matter, I can create similar images anywhere. But in terms of concentration and freeing my mind of my daily responsibilities, it is very important to get away. I have a full time job, a large family and many professional responsibilities, and I find that it’s difficult for me to concentrate when I’m on my home turf. However when I get away I’m able to leave all those things behind me. The best thing about being away is that I’m able to focus on just one thing: creating.

So travel has become very important for me. Many of these trips are to visit my children who have been stationed around the world. We visited my Marine Corp son who was stationed in Japan, my Peace Corp son in Ukraine and Poland and next year I’ll visit a son in Russia and Croatia. I am very fortunate to have family in these places because I probably wouldn’t have been brave enough to venture there without them. However next year will be a first for me as I visit Iceland by myself.

I do also travel within the United States. I go to Death Valley every January, the Oregon coast every September and I’m looking to add a third location, probably Hawaii. I like going back to the same spot each year because I can continue working on an idea, but once I’ve lost interest in that idea, I find a new location.

There are so many photographers working with long exposure photography techniques in black and white that sometimes it is hard to be original. Yet your work is very original. Can you give our readers any tips for finding an original approach to long exposure photography?

One of the side effects of the internet is that everyone quickly knows what everyone else is doing. When someone creates a new look, it seems as if overnight everyone is copying that look. I did that for many years, imitate others look, until I realised that I wanted to be more than an imitator or copycat. I want to create my own unique work and that is what I focus on, ignoring what others are doing.

I have a friend who thinks the key to success is to photograph something that nobody else has photographed before. He once told me that he had discovered something unique: frozen chickens. He said that he would always have a frozen chicken in his images (to this day I’m not certain if he was kidding or not!). In my opinion success is not about finding a subject that’s not been photographed before (I doubt there are many such things) but rather creating something unique, from your own vision.

I never focus what others are doing, I simply go down my own path. I am unaware what others are creating because I practice something that I call Photographic Celibacy. It’s the practice of not looking at or studying the work of other photographers. I do this to reduce the number of images floating about in my head and to reduce their influence on my own work. I find that when I see a great image, my first thought is “how can I do that?” Then I catch myself and remember that I do not want to imitate, but create. I’ve practicing Photographic Celibacy for five years now and it has been very helpful, but I still have some iconic images floating around in my head and when I go to the grocery store I have to admit that I still look at the bell peppers! But I’m doing better at not imitating others.

Most people who hear about this practice think I’m crazy, they believe that imitation is how we build our skills and grow creatively. I disagree, I believe imitation is harmful because it retards the development of our own vision.

Can you tell us a little about The Lone Man series? What inspired it? What are you trying to express with these images?

Like most of my series, the Lone Man was an idea that I just stumbled upon and spontaneously created. Whenever I get an idea for a new project, I write it down on a long list. However the truth is that I’ve never once used one of those ideas, all of the ideas for my portfolios have been spontaneous and just took off like a wildfire.

That’s what happened with the Lone Man series. I was in North Laguna at one of my favourite dive spots, creating long exposures of the water. It was a pretty crowded day at the beach and so people were out on the rocks looking for creatures in the tide pools. A group of people were in my shot and I was impatiently waiting for them to leave. While waiting I decided to do a test exposure so that I’d be all ready as soon as they left. After the 30 second test exposure, I noticed that one of the people had stood still for the entire 30 seconds and I recognised his body language. It was pensive, thoughtful and you could tell the man was thinking about things larger than himself.

Soon I started noticing this effect in a lot of people, they would come to the edge of the world and just stare off into the distance. I began photographing these people and the Lone Man series was born. Here is the artist statement for this series:

Something unusual happens when a person stands on the edge of the world and stares outward. They become very still and you can almost see their thoughts as they ponder things much greater than themselves:

Where did I come from?

What is my purpose?

What does it all mean?

What is beyond, the beyond?

Do I make a difference?

Is there more?

At that moment they are The Lone Man, alone with their questions and thoughts about life, the universe and beyond. People are affected by this time of meditation and they often vow to make changes in their lives. But this moment is short lived as these weighty thoughts are replaced with more immediate concerns:

Should I eat at McDonalds or Burger King and should I try that new green milkshake?

Normally I do not comment on what my images mean, sometimes because they are just beautiful images and don’t have any deeper meaning, and often because I think it’s the viewer’s job to decide what they mean. But in the case of The Lone Man, I have revealed a bit of what I’m thinking about in my artist statement. When I was creating these images I was impressed at how standing at the edge of the world causes people to ponder their smallness and their purpose in life.

So many people have asked me “how did you get those people to stand still for 30 seconds” and “did you ask them to stand still?” I didn’t have to ask people to stand still because this is just what people do! You could see them deep in thought as they stood there, often for several minutes, and pondering the “bigger questions” of life.

The last part of my artist statement is a little dig, at how little time we spend thinking about those bigger issues and how easily we are brought back to our own petty concerns; my burger wasn’t cooked right, I don’t get a good cell signal at my house, the guy in front of me is driving so slow etc. So much of what we concern ourselves with is so unimportant in the larger scheme of things.

Another series I like is Monoliths. What draws you to photographing seascapes? What’s the appeal of the giant rocks that appear in these photos?

I grew up in Southern California and spend my youth at the Huntington Beach pier, bodysurfing at lifeguard tower number 1. I spent countless hours diving Laguna, La Jolla and Catalina. The ocean was a large part of my life until I moved to Colorado in 1993. Truthfully the ocean is the only thing I miss about California and whenever I visit, I am drawn back to it.

Photographing the movement of the ocean with long exposure is just a part of my vision, it’s how I see the ocean. To photograph it with a static image, seems to me a sin!

I have always had a “thing” about Monoliths, first when I was a young boy and read Thor Heyerdahl’s “Aku-Aku, the Secret of Easter Island.” Those stone giants really captured my imagination and I wondered who created them, how and why?