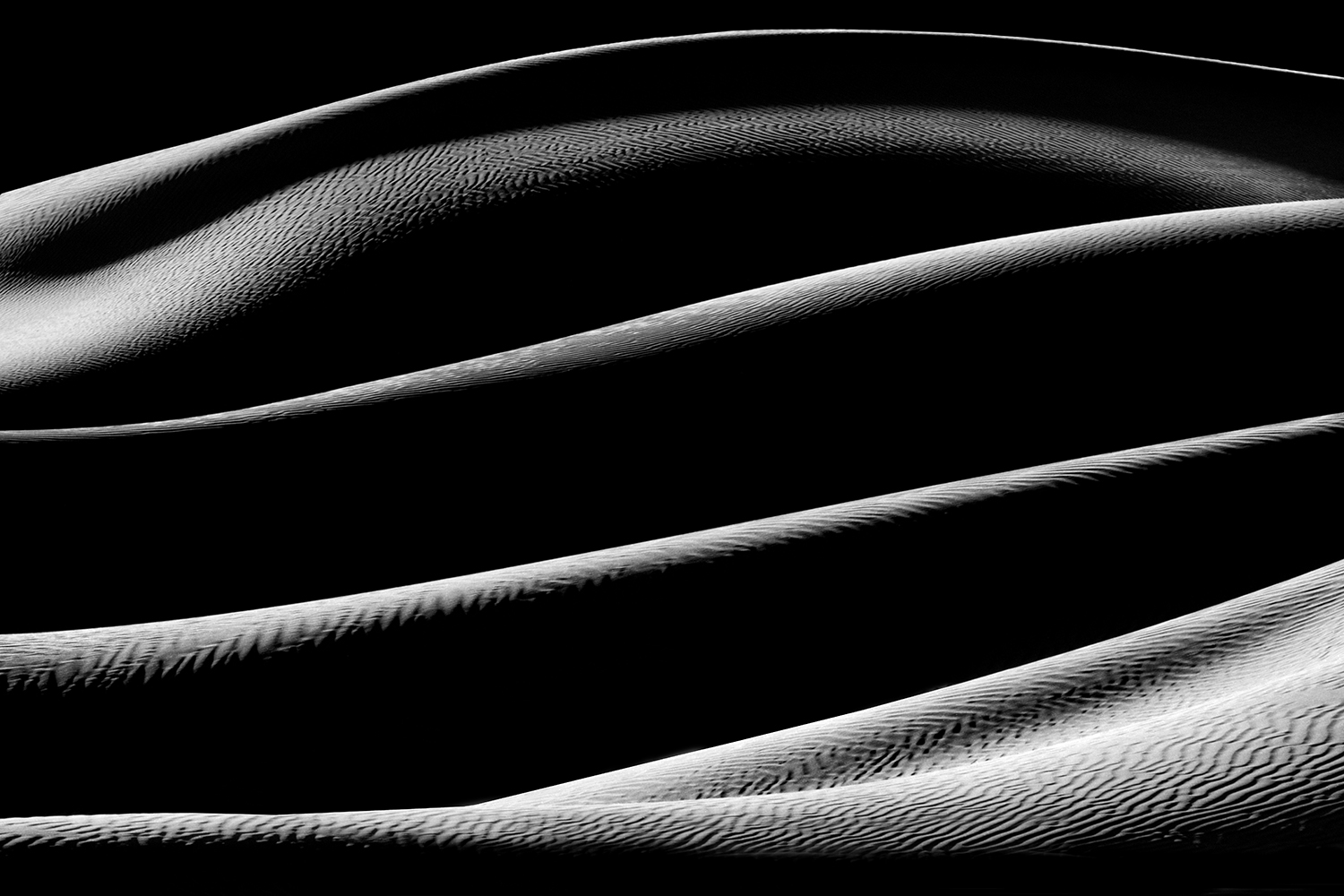

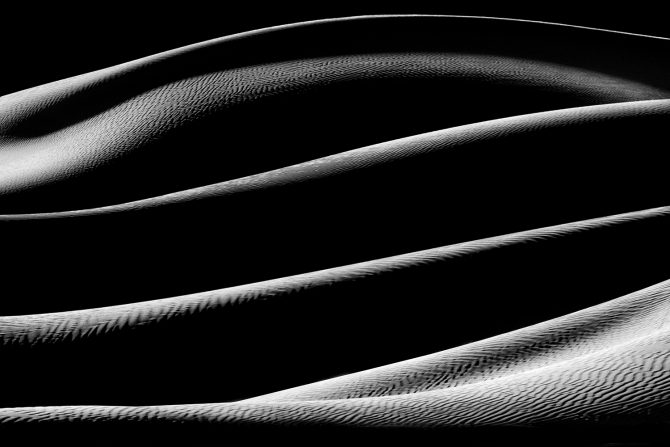

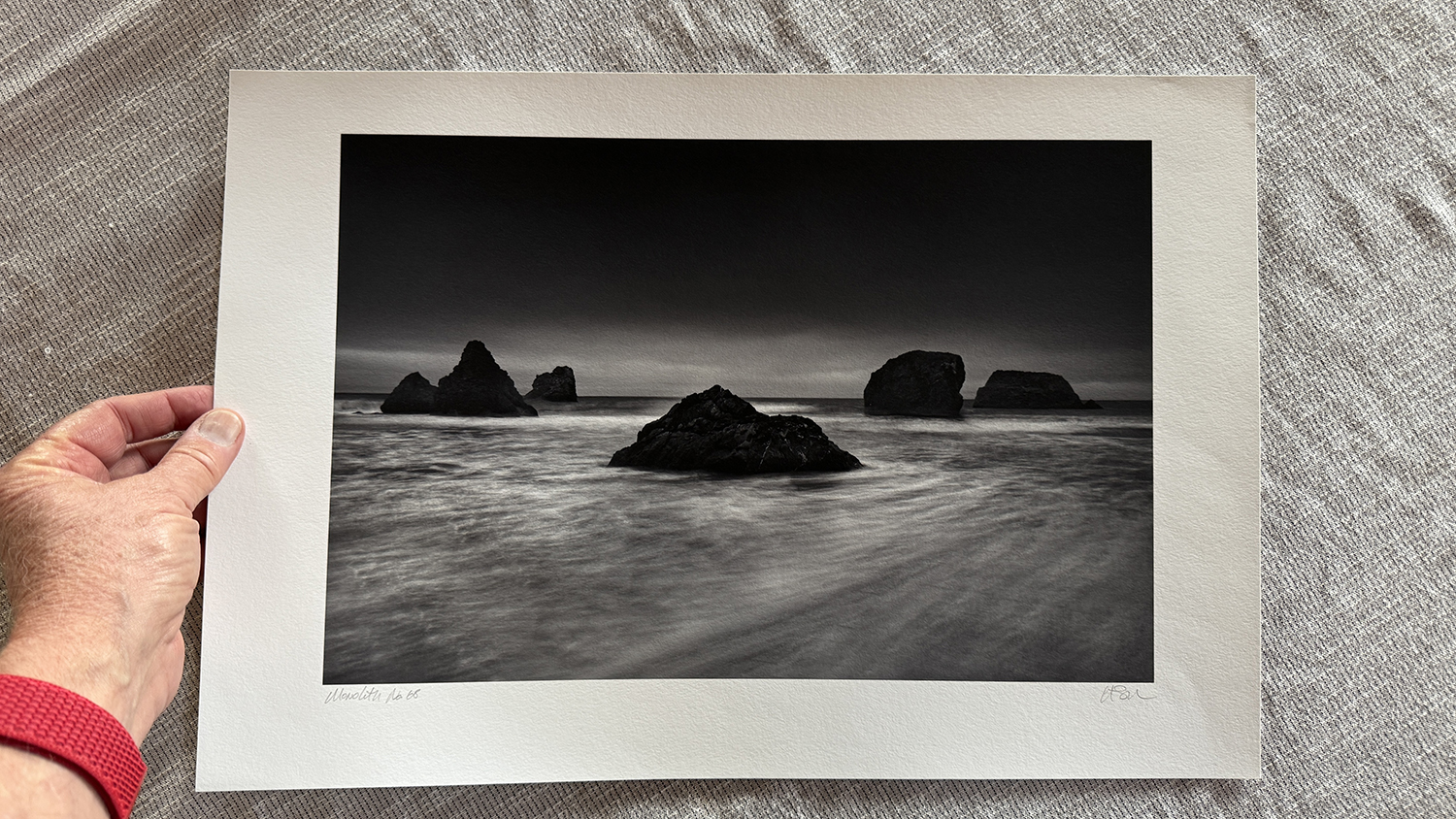

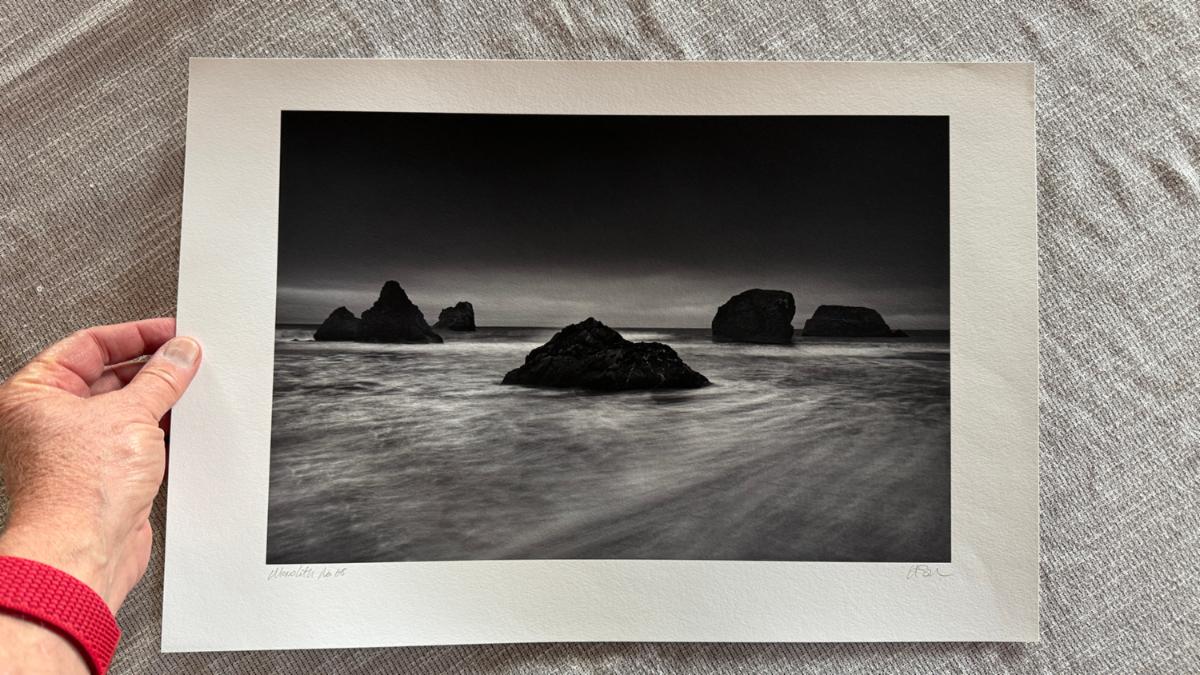

| Recently, a woman from Australia wrote me and said, “Here I am, almost 84, and still have neither time nor respect for silly restrictive rules of any description.” She made me think about how, when you get older, you have less tolerance for distractions and silliness, or “noise” as I call it. I’ve found that as I’ve aged, so many things don’t matter to me anymore. For example, I have no desire to have thousands of followers so I can call myself an “Internet Influencer.” I don’t care if someone doesn’t like my work. And if I’m never recognized by the art establishment, who cares? Today I’m feeling brutally honest, and I thought I’d give you my tips on how to be happier with your photography, and it’s pretty simple: just follow these 10 steps: 1) Quit reading articles that promise that you can be happy if you do these ten things! There are no easy answers, and almost everyone is trying to lure you in with headlines like this so that they can make money in some way. 2) Find your Vision! If you’ve been putting it off because the concept seems too vague or because doing the work is too hard, please commit to starting today. Nothing good comes easy, and finding your Vision is very hard…but nothing will improve your photography or your happiness more than finding and following your Vision. 3) Take a break from social media. Looking at other people’s photography isn’t going to make yours any better. Social media breeds imitation, jealousy, and discontent. “Likes” are not a gauge of how good your work is. The temporary dopamine rush you get from them will quickly diminish, and you’ll soon be looking for your next high. Social media is addictive, it shortens our attention span, and it homogenizes us into this giant, uninteresting lump of photographic goo. 4) Answer the question: Why do I photograph? Are you photographing to become famous? To make money? As a hobby? To express yourself? Be brutally honest about your motives, because only then can you move to the next step. 5) Define what success means to you. Once you understand why you create, then you can decide what success looks like for you. For years, I chased the unspoken definition of photographic success: To be famous, to have my work in a big-name gallery, to sell my prints for big dollars, and to have a book published. As I started to achieve some of that “success,” I realized that it wasn’t fulfilling or lasting, and that’s when I defined success for myself. 6) Quit reading and watching “how-to” articles and videos. Instead, use your time to photograph more. If you want to be a better photographer, then you must photograph more often; it’s a pretty simple formula. 7) Photograph where you’re at. You don’t have to photograph famous locations, National Parks, or foreign lands; your backyard will do just fine. I regret that I have contributed to the subtle and pervasive social media message that great images come from great locations. I think of Paul Caponigro’s series of fruit in a bowl, photographed in his kitchen…simple and sublime. Edward Weston, in his final years and confined to a chair with Parkinson’s, said that he ought to be able to look down at his feet and find something interesting to photograph. 8) Learn to critique your work for yourself, spend time with your images, and analyze them. What do you love about the image, and how can you emphasize that? What don’t you like about the image, and how can you minimize that? Let it sit for a week, and then ask yourself those same questions again. And do it again in another week. And again and again. Keep repeating this cycle until no more changes are made; that’s when you know it’s done. Sure, it’s easy to ask someone what you could’ve done better or differently, but that’s just their opinion, and you really don’t learn by listening to others’ opinions. If your images are a form of self-expression, then someone else’s opinion is irrelevant. Your opinion is the important one. 9) Learn not to care what others think about your work! (both the criticism and the praise). My continual goal is to be like Georgia O’Keeffe, who said, “I decided to accept as true my own thinking. I have already settled it for myself, so flattery and criticism go down the same drain, and I am quite free.” Yes, it’s a hard thing to do, but as you find and follow your Vision, you will gain confidence in what you’ve created and can withstand the fickle winds of public opinion. 10) Photograph what you love and how you love to photograph it. Don’t let rules, common wisdom, judges, teachers, mentors, and social media determine your course. Find and follow your Vision and create what you love. And here’s a bonus tip for those of you who have a paid subscription to my newsletter: (fyi: there is no paid subscription) 11) Create honest work. I define that as work that was created from my Vision; the idea was mine (not borrowed or stolen). It is work I created with no thought of how others would receive it, and it is work I love regardless of how others feel about it. Do you want to be happier with your photography? Quit reading articles like this one and go out and photograph! |